Three State Tax Cut Lessons for 2023

The past two years were a great time to make state tax policy. Booming revenue collections combined with hundreds of billions of dollars from Congress in pandemic-related aid took tough budget decisions off the agenda in most states.

In fact, 29 states passed major tax cuts in 2021 and 35 states did so in 2022, even as most states significantly increased spending and refilled rainy day funds. However, policymakers still face tradeoffs when cutting taxes during extraordinary fiscal times.

In a new report, we analyzed five states—Connecticut, Delaware, Mississippi, Utah, and Vermont—that either cut individual income tax rates, expanded tax credits, or sent out one-time rebates in 2022. We studied each using the Tax Policy Center’s state income tax model.

As some states consider another round of tax cuts in 2023, here are three lessons from 2022.

Income tax rate cuts benefit households with a lot of taxable income

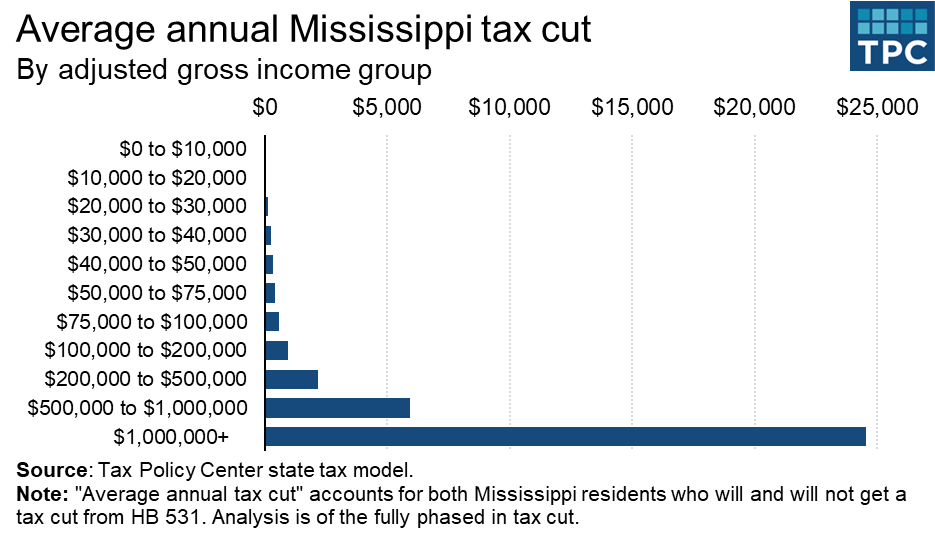

In all 11 states that cut individual income tax rates in 2022, the largest direct benefits went to the highest earning households. That’s because the benefits of a tax rate cut are relative to a household’s tax bill. For example, here’s what happened when Mississippi created a flat tax and cut the rate from 5 percent to 4 percent. (That rate reduction is scheduled to occur over three years, but we modeled it as if it takes effect immediately to simplify cross-state comparisons in the report.)

That is, Mississippi households earning more than $100,000 got thousands of dollars in annual average tax cuts because they pay tens of thousands of dollars in state income tax every year. (Note: The unit of analysis is a tax unit; we use “households” throughout this post for simplicity.)

Conversely, a household that pays little or nothing in income tax gets little or no benefit from a rate cut. This group mostly includes low-income households, but it also can include retirees. For example, roughly one-in-five Mississippi households earning between $50,000 and $75,000 in adjusted gross income got no benefit from the tax rate cut, most likely because they receive Social Security benefits, pensions, and other types of retirement income that are tax-exempt in Mississippi.

If the goal of policymakers is boosting economic growth, a rate cut could help, though the tax-growth calculation is more complicated than that. But a rate cut itself won’t do much for working families. To do that, a state would have to create or expand a refundable tax credit.

Targeted tax cuts produce targeted benefits

Connecticut expanded its earned income tax credit (EITC) and Vermont created a child tax credit (CTC) for low-income households with children younger than age 6. Because both credits are refundable, they benefited households with little or no taxable income.

In 2022, 10 states created or expanded an EITC or CTC. While benefits and eligibility rules varied, each of these states gave a big tax cut to specific households—largely low-income households with children—while limiting revenue costs. However, this also meant many households saw no benefit.

For example, while a CTC-eligible family in Vermont got an average annual tax cut of more than $1,000, only one-in-ten households earning less than $100,000 was eligible. Similarly, while a state EITC (based on the federal eligibility rules) is more broadly available and can provide hundreds of dollars in tax relief to working families, it only benefits roughly a quarter to a third of all low-income households.

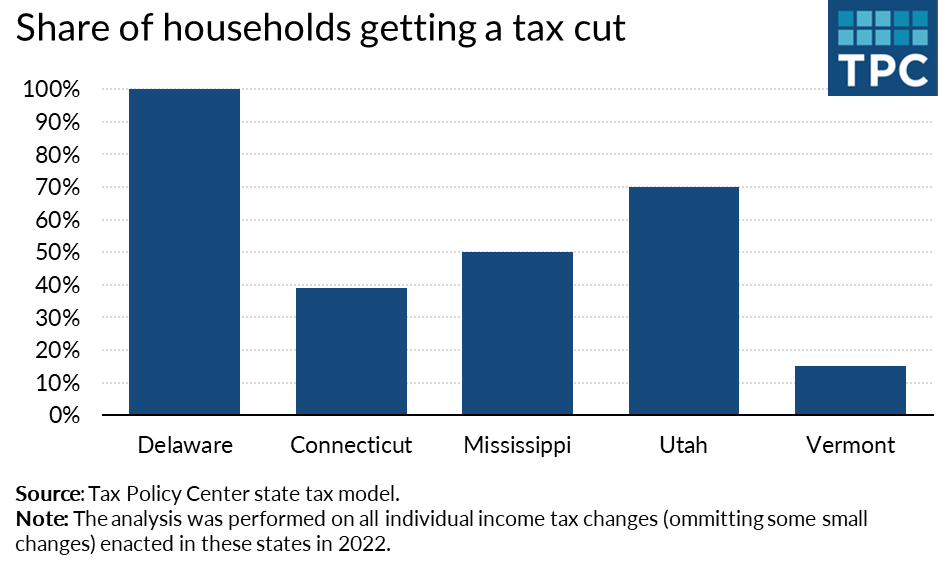

In contrast, Delaware sent one-time tax rebates to all filers, and tax rate reductions in Mississippi and Utah reached a larger share of households.

Good times don’t last forever, but your tax cut might

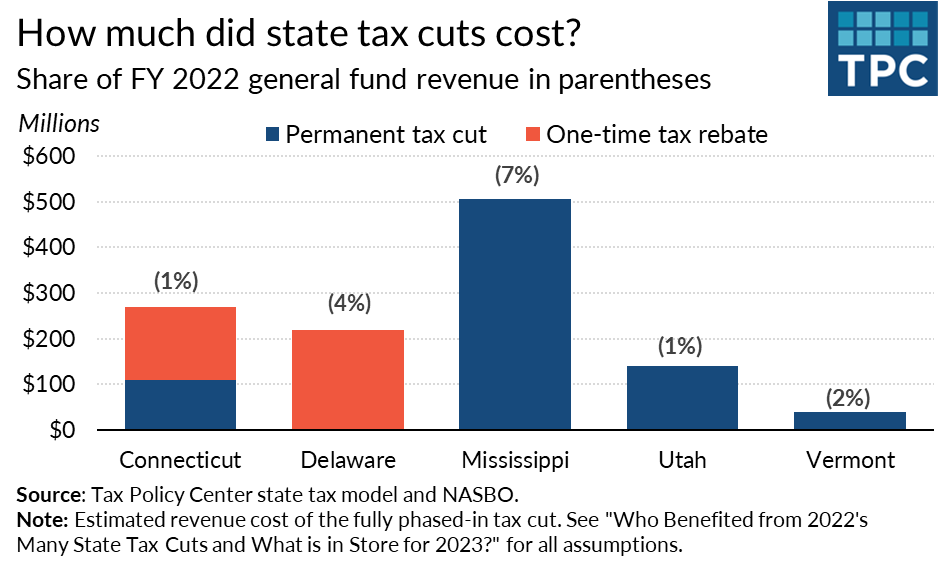

Delaware passed a big tax cut in 2022. The roughly $220 million cost was equal to 4 percent of its FY 2022 general fund revenue. But because it was a one-time rebate, it won’t affect future budget decisions. Say what you will about tax rebates, but Delaware and the other 17 states that sent them out in 2022 matched a possible one-time fiscal moment with a one-time tax cut.

Meanwhile, Mississippi’s tax cut was both big (7 percent of its FY 2022 general fund revenue) and permanent. Income tax rate reductions don’t have to cost states a lot of revenue—Utah’s was relatively small—but, in general, new or expanded refundable tax credits, such as those in Connecticut and Vermont, cost far less than tax rate cuts.

While recession fears persist, state finances mostly remain strong as policymakers meet in state capitols to hammer out new budgets. As such, states that cut income tax rates in 2021 or 2022 could consider refundable credits that help households that did not benefit from previous tax cuts, and states that passed one-time rebates could consider fiscally responsible permanent tax relief.

But at some point, perhaps soon, the economy will turn, and states that passed bigger, permanent tax cuts will face tougher fiscal choices because of those tax cuts. If and when that happens, they should remember what taxes they cut, and who they benefited, in that new budget environment.