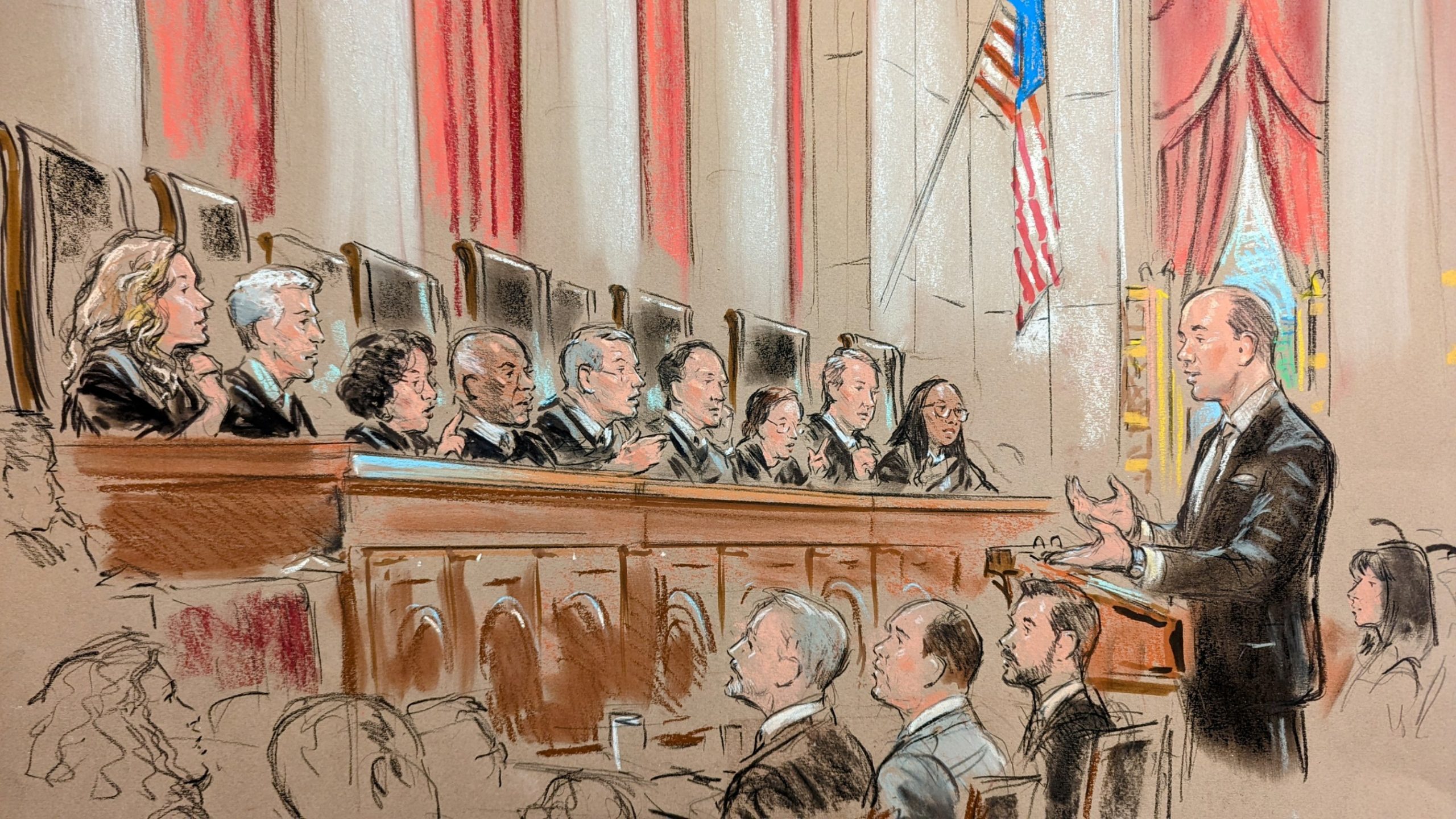

The Supreme Court hears the “false statements” case brought by the heir to Chicago’s political dynasty

CASE PREVIEW

The Supreme Court will hear on Tuesday the case of a Chicago alderman who spent four months in federal prison for lying about loans he had taken out from a local Chicago bank and failed to repay. Patrick Daley Thompson, a member of the city’s most famous political dynasty, hopes that his case will be the latest in a series of cases in which the justices push back against what a majority of the court has seen as overreach by federal prosecutors.

Thompson is the grandson of Richard J. Daley, who served as mayor of Chicago from 1955 to 1976, and the nephew of Richard M. Daley, who served as mayor from 1989 to 2011. He was elected in 2015 to the City Council, representing a South Side district, and reelected in 2019.

Thompson took out three loans totaling $219,000 between 2011 and 2014. This was from Washington Federal Bank for Savings on the South Side, where the Daleys made their name. Thompson used the money for a tax bill to pay, to pay an equity contribution at the law firm he was a partner in, and to repay a loan he owed to another bank. He did not sign paperwork for the second or third loans. The bank did not request any additional payments. The bank did not request any additional payments.

After the bank failed in 2017, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which became the receiver for the bank, hired a loan servicer, Planet Home Lending, to try to recover some of the money owed to the bank.

In Feb. 2018, Planet Home Lending sent Thompson an invoice for the principal on his loans plus interest: a total of $269,120.58. Thompson called Planet Home customer service and insisted that he only borrowed $110,000, the amount of his first loan for which he signed paperwork. A week later, he spoke with two contractors for the FDIC, telling them that he that he had borrowed $110,000 for “home improvements.”

Later that year the FDIC and Thompson settled the debt, with Thompson agreeing to pay the principal of $219,000 but not the interest.

Two-and-a-half years later, Thompson was charged with violating a federal law that makes it a crime to make false statements to influence (among other financial institutions and federal agencies) the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. He was also accused of filing false income taxes, but these charges are not before Supreme Court. He was convicted by a jury, sentenced to four months in prison, and ordered to pay restitution to cover the $50,000 in interest that he still owed.

Thompson challenged his conviction. He admitted that his statements were misleading because he did not mention the second and third loan, which totaled $109,000. He insisted that his statements were not false because he only stated that he borrowed $110,000 from Washington Federal, not that he owed that amount. Thompson told the justices that in 1982, the Supreme Court refused to interpret the law to cover bad check writing, rejecting the argument of the government that it was a false statement to imply that there was enough money in the bank account to cover the check amount. In so doing, Thompson emphasizes, the court also rebuffed any suggestion that the law “should be construed non-literally to sweep in more conduct than the statute prohibits.”

Indeed, Thompson notes, Congress has in other laws prohibited “false or misleading” statements or omissions that would make statements misleading. It would not need to do either of those things if the reference to “false” in the law under which Thompson was convicted had the broader meaning that the government attributes to it, he contends.

Thompson cautions that the government’s interpretation of the law would criminalize a “vast range of everyday statements” by both would-be borrowers and debtors. For example, he asserts, a homebuyer who tries to negotiate a better interest rate by indicating that she has an offer from another lender, but who omits that the other lender also requires a larger down payment, could “be sent to prison for thirty years and fined a million dollars.”

And this would be true, Thompson adds, even if the borrower’s misleading statements had no effect on the lender’s decision, because all that matters under the law is whether the statement is made “for the purpose of influencing” a financial institution.

The federal government counters that holding defendants like Thompson liable would be consistent with the commonsense meaning of a “false statement” – which it defines as one that is “untrue or deceptive.” This can include, the government says, statements that are, “in context, inaccurate or incomplete.” For example, the government contends, a driver makes a false statement if he tells a police officer that he “had just one cocktail,” leaving out that he also drank four glasses of wine.

The government argues that its rule is also consistent with a 1938 Supreme Court decision that predated the reenactment of the federal criminal code, in which the justices interpreted a law that prohibited the “making of any statement, knowing it to be false” to apply to “false and misleading representations.”

The government dismisses as “unfounded” Thompson’s suggestion that the law could ensnare borrowers and debtors based on their “strategic puffery during negotiations.” Thompson cites no examples of anyone who was actually prosecuted in such a scenario, the government observes, “and such puffery has not traditionally been understood as fraudulent.”

But even if the law were limited to statements that are literally false, the government continues, Thompson’s conviction could still stand because he made false statements: He told the FDIC contractors that he had “borrowed $110,000,” he “disputed” the amount of the invoice that he had received from Planet Home, and he told the FDIC that he had taken out the first loan for “home improvements,” rather than for his equity contribution to his law firm.

A decision in the case is expected by summer.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.