The Spanish Supreme Court Sentences the Trucks Cartel

Introduction

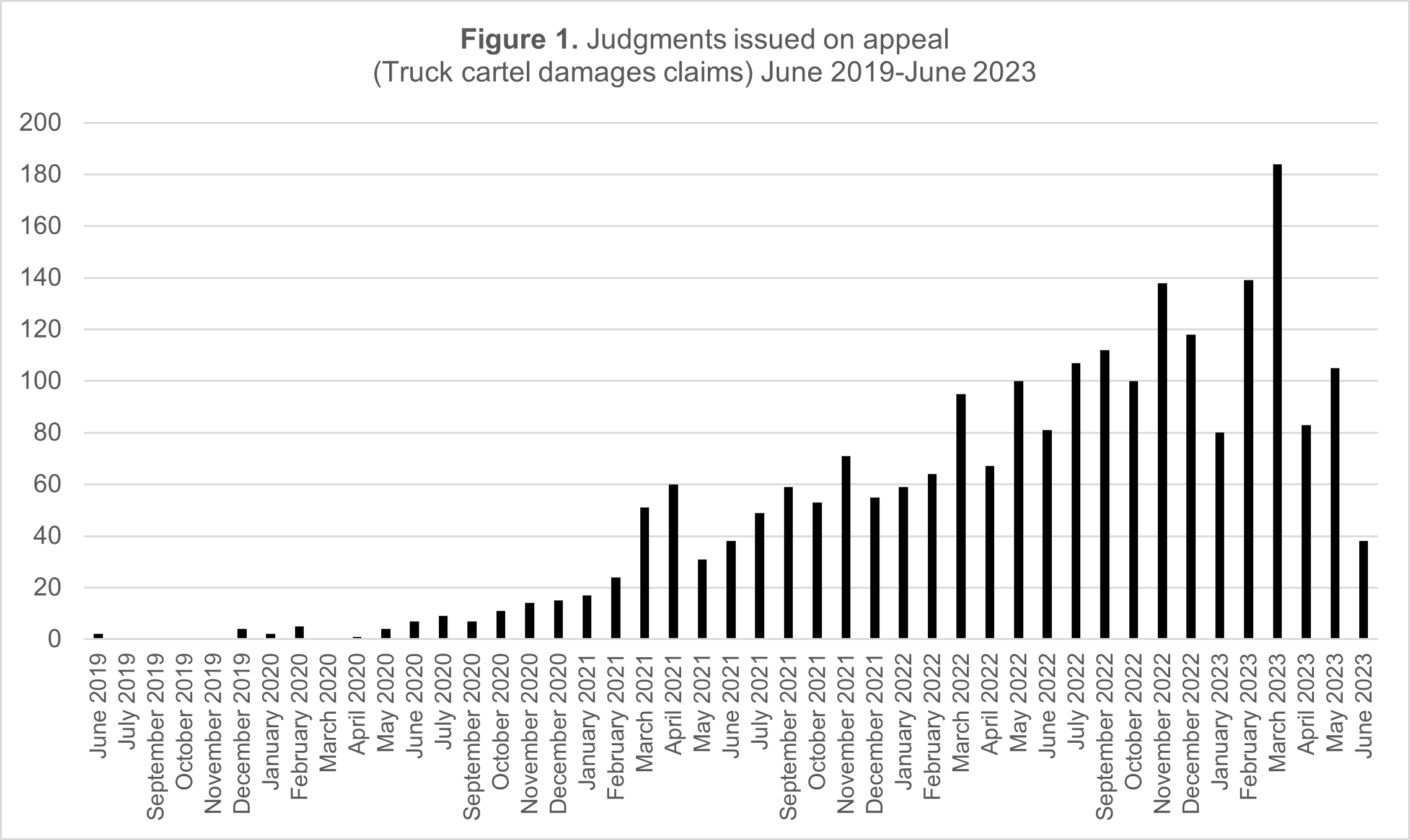

Three weeks ago, the Spanish Supreme Court delivered its first rulings on damages claims in the trucks cartel. Given that Spanish courts have been the most active in the EU on this case (see the stream of judgments issued by the Courts of Appeal in Figure 1, 85% are available at CENDOJ), there was great expectation regarding what the top court would say concerning many issues posed by blooming antitrust damages litigation. Indeed the rulings would guide not only the evolution of the claims in the case (including those recently filed against Scania) but also influence the incipient damages litigation landscape in other cases (e.g., follow-on damages claims in the automobile manufacturers cartel, reported here).

Before the Spanish Supreme Court, only the German Supreme Court had ruled on the case in three judgments (KZR 35/19, KZR 19/20 and KZR 20/20: on the merits but not on quantum). In other jurisdictions, the highest courts had ruled on accessory matters: international jurisdiction (Norwegian Supreme Court HR-2019-2206-A and Supreme Court of Israel, RA19/6646) or access to evidence (French Cour de Cassation, n°19-25065). Likewise, the Spanish Supreme Court itself had ruled before on jurisdictional issues -later addressed also by the CJEU in Volvo C-30/20– in over a hundred orders.

Fifteen judgments of the Spanish Supreme Court

The fifteen judgments of the Supreme Court were decided in appeals filed against judgments of five Court of Appeals (Barcelona, Pontevedra, Valencia, Vizcaya, and Zaragoza), which in all -but two cases (ES:APV:2020:3547 and ES:APV:2019:4150)- had awarded damages to claimants (see table below). Four different Supreme Court magistrates penned the judgments after court hearings were conducted a month ago (a recording of which can be accessed here and here).

Table 1. Supreme Court judgments on trucks cartel damages claims

The judgments resolve the first appeals that reached the Supreme Court against judgments handed down by the Courts of Appeal in late 2019 and early 2020.

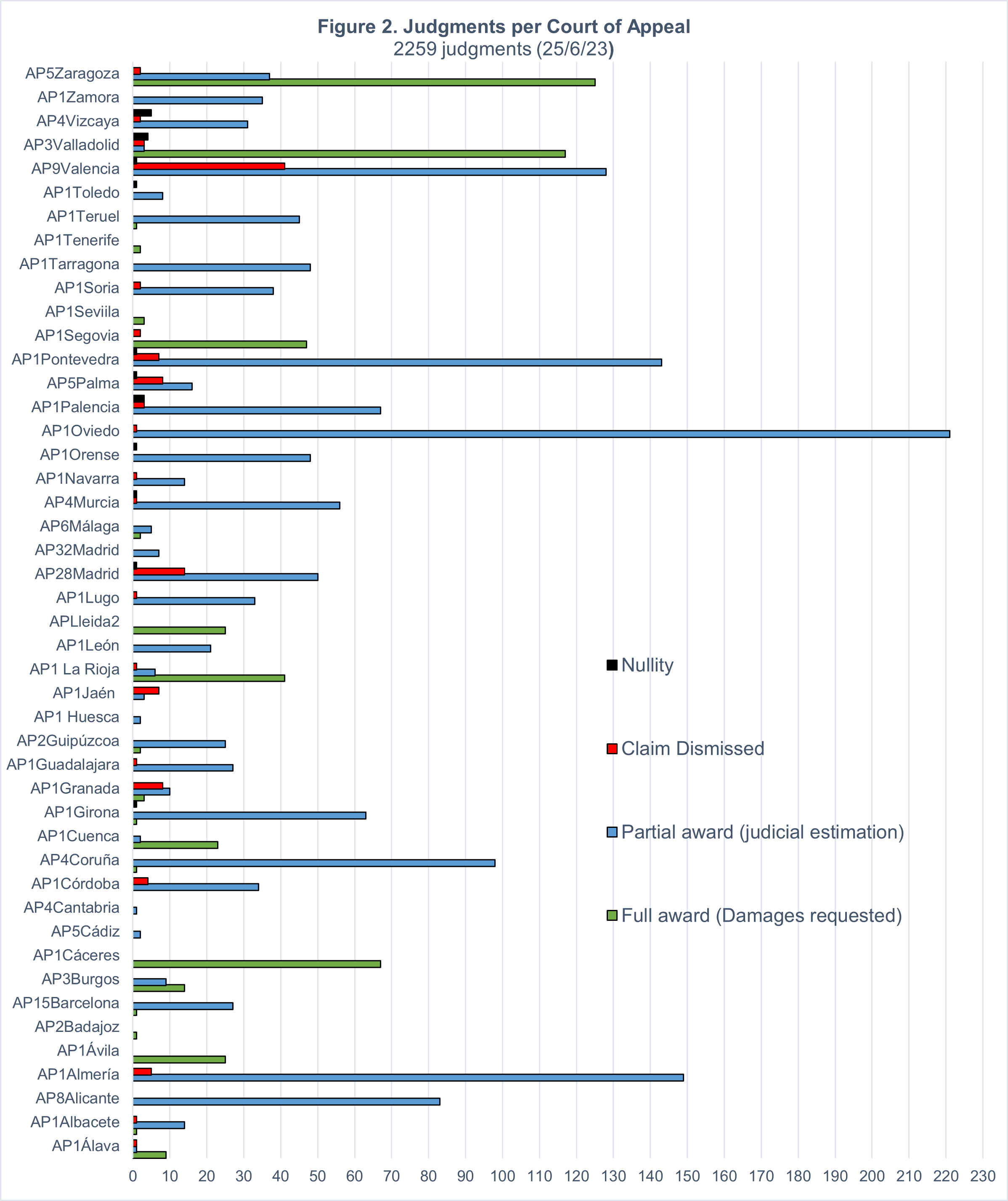

Most of the judgments appealed come from the Court of Appeal of Valencia (8/15), which on the path of the groundbreaking judgments of commercial court 3 (Eduardo Pastor, see ES:JMV:2019:34 and ES:JMV:2019:187), was one of the first Courts of Appeal to rule on the matter (ES:APV:2019:4150). At present, in number of judgments delivered the Court of Appeal of Valencia has been overtaken by the Court of Appeal of Oviedo and Zaragoza (see Figure 2). Valencia is still the Court that has rejected more claimants’ suits, mostly by deeming them time barred. It will need to undo two of its rulings (ES:APV:2020:3547 and ES:APV:2019:4150), as the Supreme Court has revoked them.

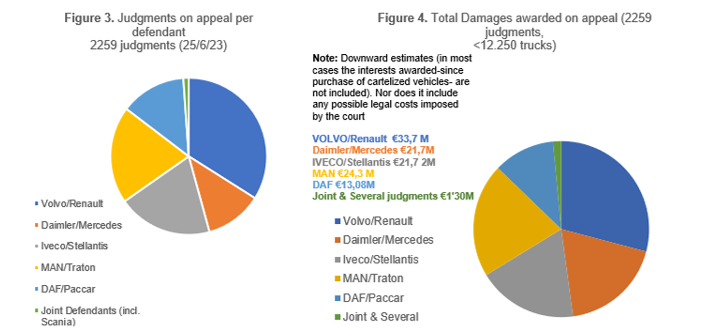

On the other hand, as Table 2 shows, in comparison with the share of the total judgments per defendant that have been delivered on appeal, in the Supreme Court judgments Iveco/CNH is over-represented, and Volvo/Renault is under-represented. Figures 3 and 5 illustrate the share per defendant of the total number of judgments (Figure 3) and the damages awarded against them (Figure 4).

Table 2. Defendants in Supreme Court judgments on trucks cartel damages claims

Defendants’ appeals

Most of the appeals before the Supreme Court were initiated by defendants, although they were joined by claimants in five appeals. Fourteen of the defendants’ appeals, based both on procedural and substantive grounds, were rejected. In addition, and not a trivial issue, defendants were ordered to pay the costs in nine appeals. Only one of the defendants’ grounds of appeal -concerning the quantum of damages- was partially accepted (ES:TS:2023:2475).

Claimants’ appeals

Two of the five claimants’ appeals were accepted, with the cases being sent back to the appeal court to rule on them again (as the judgments that declared them time-barred were quashed, ES:TS:2023:2474 and ES:TS:2023:2476). These two judgments are more straightforward than the others, as the Supreme Court played safe, following closely the earlier CJEU judgment in C-267/20 Volvo & DAF.

Given that article 74 of Spanish Competition Act (derived from article 10 of Antitrust Damages Directive) was applicable to the trucks cartel damages actions, claimants had a five-year limitation period (instead of the one-year limitation period set out in the rules previously in force) and, thus, they could not be time-barred. However, the Supreme Court ruling is limited to determining the (longer) limitation period for claims in this case, avoiding any decision on whether the communications addressed to the infringers but sent to their subsidiaries’ domiciles were valid for the interruption of the limitation period (as I discussed in the last part of my post in Almacén de Derecho 27/8/20). Probably, the answer to that question will have to wait for the CJEU ruling in C-632/22 Transaqui, lodged last year by the Supreme Court in relation to a connected issue.

On the other hand, although the dies a quo in damages claims following-on a final Decision of the European Commission is now crystal clear (in the trucks cartel after CJEU judgment C-267/20 Volvo & DAF and in the Euribor cartel after CJEU order in C-198/22 and C‑199/22 Deutsche Bank), we still lack some clarity regarding the computation of the limitation period when follow-on claims are initiated based on a non-final decision by the NCA (a matter in which, commercial courts have taken divergent positions in the automobile cartel damages litigation).

Apart from those two judgments that focus solely on the limitation period (and which should lead soon to two new rulings of the Valencia Court of Appeal surely mirroring what the Supreme Court held in the other cases – the circumstances therein present being the same), the rest of the Supreme Court judgments endorse the unanimous holding of the appealed judgments: claimants have a right to damages based on a judicial estimation of the cartel overcharge. As will be explained below, in the circumstances present in these proceedings, the Supreme Court confirmed the judicial estimation of the overcharge at 5% of the price of the cartelised vehicles.

“First wave” of claims…

The Supreme Court declares this initial batch of judgments decide the “first wave of claims” of the trucks cartel damages litigation in Spain. This temporal reference seems to be borrowed from the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT), that named “first wave proceedings” those that were first transferred by the High Court of England and Wales (see [2022] CAT 41), of which only those involving the claims by Royal Mail and British Telecom had been fully tried and decided (see [2023] CAT 6, which I commented here).

Any parallel with the trial and management of the proceedings in the CAT is however limited: the “wave” metaphor aptly describes the progressive and sequential management of proceedings in the CAT as a first instance court, whilst the Supreme Court is the highest court in Spain, and well over 2.000 appeals crowd its docket. Rather than “waves” in the trucks cartel damages litigation, the Spanish Supreme Court seems to be facing a tsunami.

In my view, by referring to them as the “first wave of claims”, the Court is pointing to the litigation being in its infancy and emphasizing the limitations claimants faced in the early stages when the lawsuits were filed. This is relevant, as in deciding some matters, the Court will consider the specific circumstances present when the claims were filed (“in view of the state of the matter and the litigation at the time it was submitted”” ¶24 of ES:TS:2023:2492, for simplicity reasons all references throughout the post will be made to it, this being the first judgment of the series, but the same wording can be found in all of them).

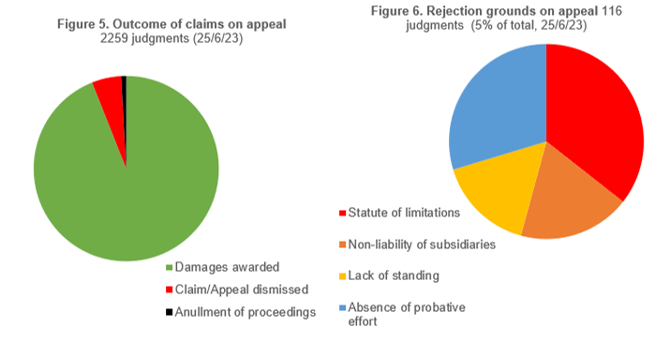

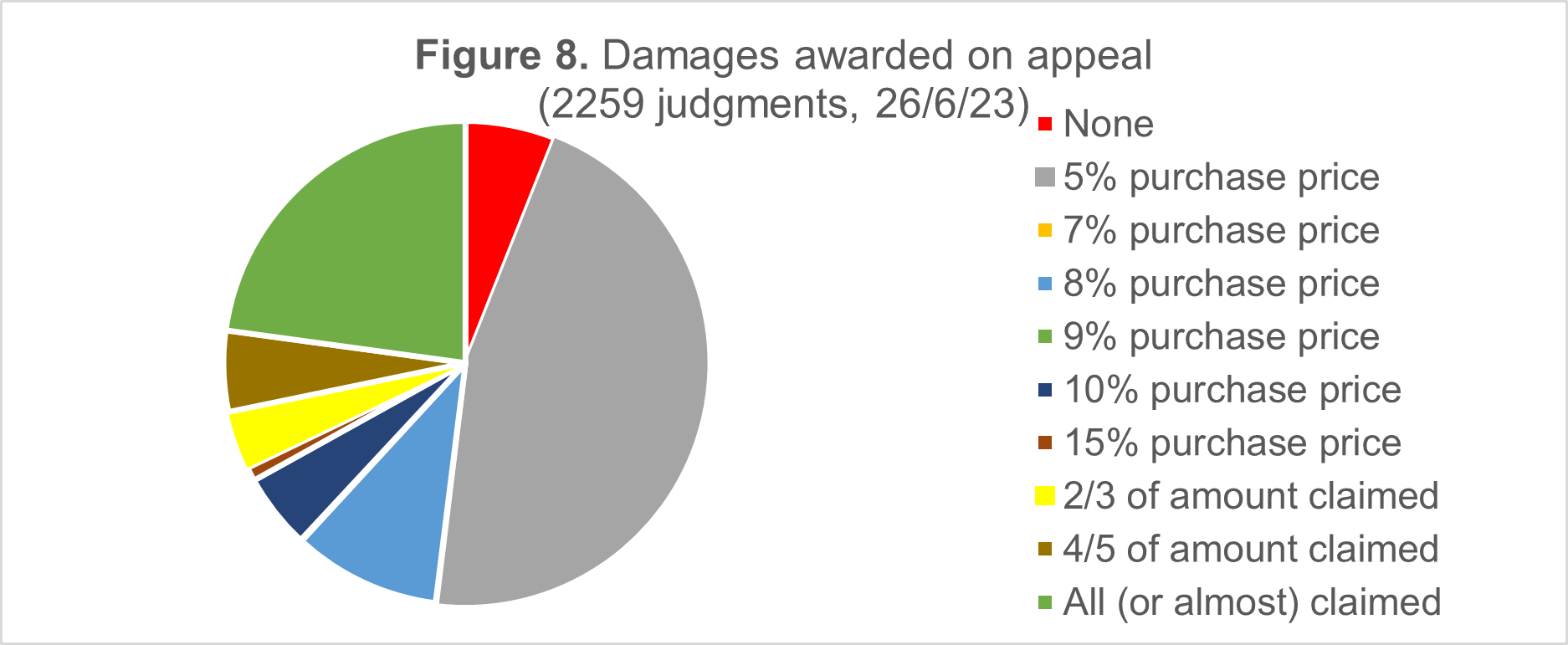

More than 5.000 judgments on the merits have been issued by over a hundred Spanish commercial judges at first instance and over 2.300 judgments have been issued on appeal by forty-six provincial courts. So far, courts of appeal have awarded damages in 95% of the judgments (Figure 5). At the appeal level, only 5% of the claims have been rejected, mainly for being time-barred (Figure 6).

The “first wave” of appeals in the Supreme Court have in common that they all were addressed to a single defendant (infringer or a Spanish subsidiary), the manufacturer of the trucks in each case. Contrary to what has occurred in other jurisdictions, and despite the absence of any obstacles to claiming compensation to the infringing manufacturers for trucks they did not manufacture, in Spain these types of claims have been infrequent (see, e.g., ES:APV:2021:170, ES:APV:2022:676). Likewise, claims addressed to several manufacturers have been rare (but see eg, ES:APPO:2021:1175, ES:APP:2022:385, ES:APLE:2022:1005, ES:APVA:2022:1372, ES:APCO:2022:753, ES:APAB:2022:954, ES:APV:2022:3705).

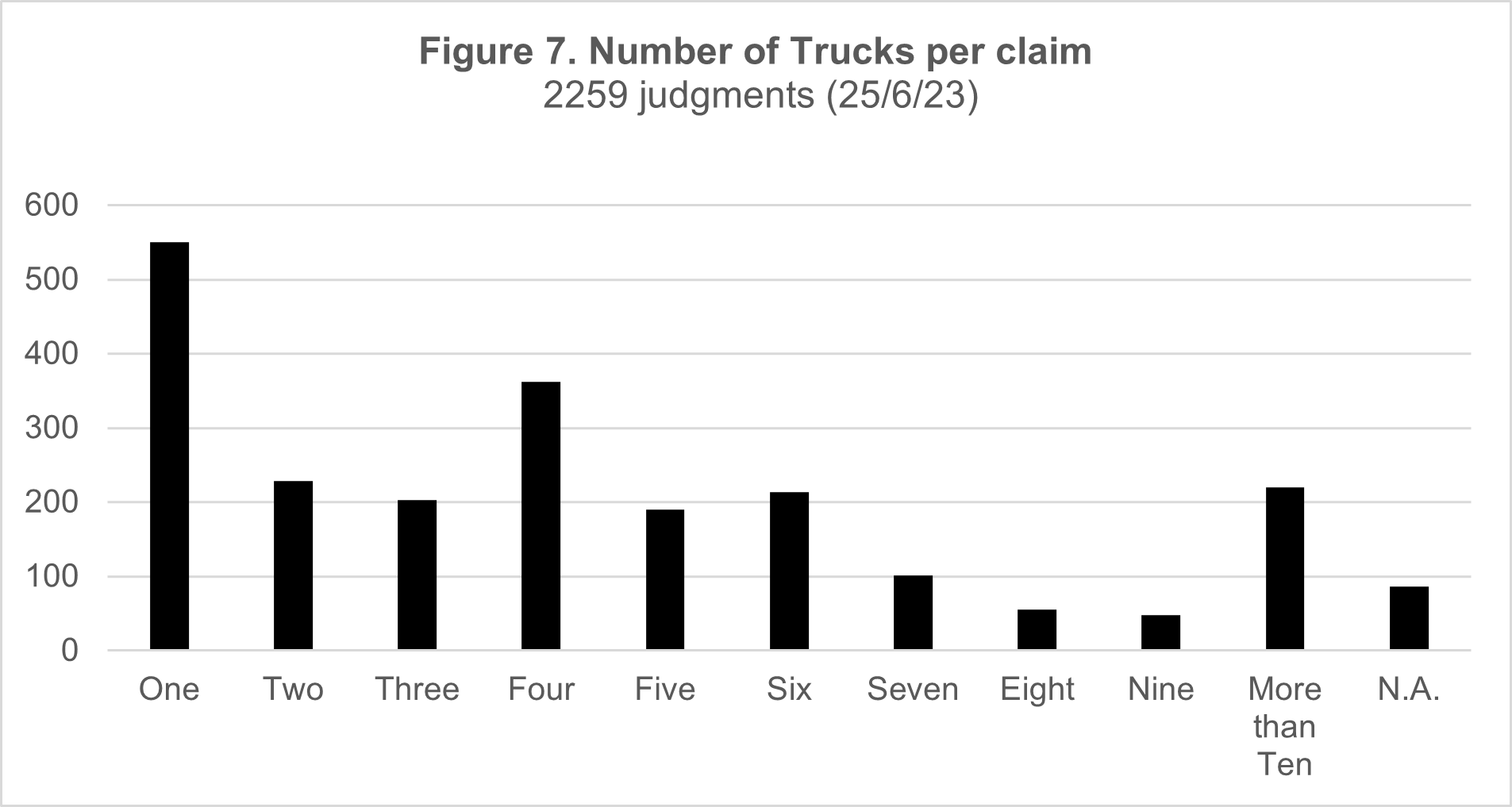

In addition, all the claims decided by the Supreme Court involved a small number of cartelised trucks (seven of them involving only one truck), totaling 149 trucks. In contrast with the large and collective claims that have been started in other jurisdictions (although the three judgments decided by the German Supreme Court involved 24 trucks: in KZR 35/19 the appeal concerned 12 trucks, 9 in KZR 19/20 and 3 in KZR 20/20), the cases decided by the Spanish Supreme Court exemplify the type of claims being decided by the Courts in Spain. Two thirds of the claims filed are individual, and 24,4% of all claims seek compensation for the acquisition of a single cartelised truck (Figure 7).

It is a straightforward preliminary observation that the Supreme Court has mostly confirmed the rulings by the Courts of Appeal. In endorsing the lower courts’ decisions, the Supreme Court repeated that it does not want to become a “third instance” decision-maker. Rejecting all the appeals filed on procedural grounds (mostly by defendants), it asserted that if the rulings by Courts Appeals are sufficiently grounded law, are properly reasoned, and do not reach irrational conclusions, it is not willing to revoke or quash them.

Naturally, each of the judgments resolves the specific procedural and substantive grounds of appeal in each case, but all of them share a common structure (with many paragraphs repeated) concerning the legal regime applicable, the harm caused by the trucks cartel sanctioned by the Commission Decision AT.39824, the power to undertake judicial estimation of harm when the quantification proposed by the claimant is unconvincing and the award of interests.

Apart from several references to its own case law and constitutional law judgments on due process, the judgments are peppered with references to the European Commission Practical Guide to the Quantification of Antitrust Harm (analyzed here) and to relevant case law of the CJEU (namely C-295/04 a 298/04 Manfredi; C-199/11 Otis, C-557/12 Kone, C-724/17 Skanska, C-882/19 Sumal, C-267/20 Volvo/DAF, C-163/21 Paccar and C-312/21 Tráficos Manuel Ferrer), adding as subsidiary support two rulings on trucks cartel damages claims by two foreign courts: the District Court of Amsterdam (C/13/639718/HA ZA17-1255 et al) and the Competition Appeal Tribunal ([2023] CAT 6).

Before we turn to some of the salient issues addressed by the Supreme Court, overall, it is worth stressing that the Supreme Court follows the path taken by the lower courts, strengthening the arguments concerning the victims’ right to compensation.

Law applicable ratione temporis

In confirming the appealed judgments, the Supreme Court definitively resolved the issue concerning the legal regime applicable in these claims. Endorsing the rulings of the Courts of Appeal, the rules adopted in transposition of the substantive rules of the Antitrust Damages Directive (Decree-law 9/2017) are considered not to be applicable to the case. Given that the cartel took place before the Directive was adopted, the Supreme Court also rejected the argument that an interpretation of national law in accordance with the Directive was possible (par. 6.3 of ES:TS:2023:2477). However, this does not have any significant implications given that many of the Directive provisions codify pre-existing rulings of CJEU and Spanish Supreme Court case law.

Subsidiary liability

Five judgments address the liability of one of the infringers’ subsidiaries (CNH Industrial N.V.), which had been considered jointly liable by the Courts of Appeal despite the fact they were declared infringers for a short period of time (17 days) by the Commission (ES:TS:2023:2492; ES:TS:2023:2472; ES:TS:2023:2495; ES:TS:2023:2473; ES:TS:2023:2475). Following C-882/19 Sumal, subsidiaries are considered liable when they belong to the same economic unit, particularly “when an entity that has committed an infringement of the competition rules is subject to a legal or organisational change, this change does not necessarily create a new undertaking free of liability for the conduct of its predecessor that infringed the competition rules, when, from an economic point of view, the two are identical” (par. 38 of C-724/17 Skanska).

In another judgment (ES:TS:2023:2476), revoking the judgment of the Valencia Court of Appeal, the Spanish subsidiary of MAN was deemed liable as part of the same “economic unit” given the existence of a “link” between the economic activity of the subsidiary and the infringement for which the holding company was declared liable (pars. 52, 41 and 46 of C-882/19 Sumal).

Binding Effect: The trucks cartel according to the Spanish Supreme Court

Furthering the unanimous understanding of Courts of Appeal, based on the evidence provided by Decision AT.39824, the Supreme Court considered that the trucks cartel was not an innocuous exchange of information among rivals, but a form of collusion among truck manufacturers, having effects in the market. Despite the fact that the Commission declared the collusive arrangement infringement “by object” of article 101 TFEU, the Supreme Court underlines that, the binding effect of the Commission Decision AT.39824 (article 16.1 of Regulation 1/2003) implies that the trucks’ manufacturers infringement consisted in collusive agreement that had an effect on both gross and net (transaction) prices of trucks. This conclusion is reached through a detailed analysis of the Decision, although the Court was necessarily aware of the limitations in the text adopted because of the leniency and settlement procedures followed in the case (although this is only explicitly mentioned in other context regarding the claimants’ constraints to access to evidence: “a leniency application and a settlement that further hinder the obtaining of the relevant documents”, par. 6.21 of ES:TS:2023:2477).

Harm and causality

The Supreme Court rebuffed the defendants’ arguments that the cartel did not cause harm to the truck purchasers. Despite the brevity of the Commission decision, the Court confirmed that it is correct to presume from the Decision that an overcharge was paid in purchase of trucks (“The facts from which the appellate court presumes the existence of the damage and the causal link are the facts found in the Decision” par. 6.6 of ES:TS:2023:2492).

Arguments put forward by defendants to support their position that the cartel had no effect were rejected as considered either to have an incorrect basis or to be unplausible (including the passing-on). In particular, borrowing from the Amsterdam District Court judgment of 11/5/21 (C/13/639718/HA ZA17-1255 et al, analyzed in Almacén de Derecho 1/6/21) in relation to the argument regarding the “tidal wave” effect, the Supreme Court explained that any potential discount obtained by truck purchasers would have absorbed or eliminated the overcharge (“if there is a cartel that has raised gross prices, those possible discounts will have been produced from a higher price level than if the cartel had not existed“, par 6. 11 of ES:TS:2023:2492; “from a logical point of view, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it cannot be admitted that a collusive agreement on gross prices of the characteristics of the cartel to which this litigation refers does not end up being transferred to the net or final prices, since, although various factors or variables may influence their final translation, the former are the starting point for the latter” par 6.4 of ES:TS:2023:2477). The cartel affected truck buyers, as the overcharge in gross prices became later an overcharge in net prices:

“It is not understood why the intermediate levels of the market (the national subsidiaries in charge of distribution and the dealers, whether independent or dependent on the manufacturers) would have absorbed in their commercial margins for 14 years the gross price increases caused by the unlawful conduct of the manufacturers, thus avoiding their repercussion on the final purchasers” (par 6.11 in fine of ES:TS:2023:2492).

Although the Supreme Court avoids explicitly endorsing the presumption of harm ex re ipsa that some Courts of Appeal had declared in their judgments, it emphasized that the trucks cartel was an “extremely severe infringement of competition law”. Following article 386 of the Spanish Civil Procedure Act (“from an admitted or proven fact, the court may presume the certainty, for the purposes of the proceeding, of another fact, if between the admitted or proven fact and the presumed fact there is a precise and direct link according to the rules of human judgment”), it found that the evidence provided in the Decision was sufficient to determine, absent any proof to the contrary by the cartelists, that the trucks cartel caused harm (par. 6.13 of ES:TS:2023:2492, repeated in the rest).

Finally, in two judgments, the Supreme Court further held that the pernicious effects of the cartel in the purchase price of trucks extended beyond the “official” end date of the cartel on 18/1/2011 due to a “lag effect” (par. 10.25 of ES:TS:2023:2480 and par. 9.24 of ES:TS:2023:2479). The German Supreme Court had already pointed in that direction, when it ruled that a compensation claim was admissible “for the vehicle purchased in 2011 and thus after the end of the cartel, as the price lists for that year were subject to cartel agreements in the previous year” (par. 36 of KZR 35/19).

Calculating the amount of the cartel overcharge

As in any antitrust damages claim, calculation of the amount of the cartel overcharge is difficult, given the need to estimate what would have been the price absent the infringement. In deciding upon the damages claims in the sugar cartel the Supreme Court had already cautioned about this: any calculation made is inaccurate due to the “impossibility of perfectly reproducing what the situation would have been had the unlawful conduct not occurred” (ES:TS:2013:5819).

In the trucks cartel, the features of the cartel make the calculation of the overcharge very difficult (“very serious difficulties in the quantification of the damage”, par. 4.4 of ES:TS:2023:2472), hampering the use of the standard tools and methods typically used in these types of cases (par. 6.21 of ES:TS:2023:2472). In the words of the Supreme Court, claimants not only face a limited availability of documents that could be relevant in facilitating such calculation, but any attempt is also hindered by the heterogeneity of the cartelized goods, the long timespan and broad object and geographical scope of the cartel (the cartelists holding 90% of the market).

Use of meta-data studies to calculate harm?

In every claim, but one (ES:TS:2023:2497), the claimants’ damages petitions was an overcharge extrapolated from statistics/meta-studies (mainly Florian Smuda, Cartel Overcharges and the Deterrent Effect of EU Competition Law, ZEW 12-50), regardless of the features of the trucks cartel and the products concerned in the case. Those studies were undertaking for purposes other than the quantification of the overcharge in specific cases. Almost all Courts of appeal had considered them to be inadequate for the calculation of the trucks cartel overcharge (all but two, e.g, ES:APBA:2022:318 and ES:APCC:2020:1135), although that did not preclude them from judicially estimating the amount of harm (which is what occurred in the cases decided by the Supreme Court).

However, it should be noted that some Courts of Appeal, notably Madrid (e.g., ES:APM:2021:14305), Granada (e.g., ES:APGR:2022:1519) and more recently also Valencia (in a strange way, e.g., ES:APV:2022:3826) had deemed it insufficient, quashing the claims. That position seemed to get some support in last February’s CJEU judgment C-312/21 Tráficos Manuel Ferrer, which ruled that the “gate” to the judicial estimation of the harm “being impossible or excessively difficult to quantify by the claimant” (article 17.1 of Antitrust Damages Directive/article 76.2 of Spanish Competition Act) was only to be opened if that position was not due to the claimant’s inactivity (par. 57 of C-312/21). In addition, clarifying the doubts raised by C-312/21 Tráficos Manuel Ferrer as to whether access to the sources of evidence through article 5.1 of the Damages Directive was essential to understand that the plaintiff fulfills the sufficiency of the evidence presented by claimants: “The reference made […] to the request for the production of evidence does not imply that, in the absence of such a request, the lack of proof of the amount of the damage is necessarily attributable to the plaintiff’s inactivity” (par. 6.19 of ES:TS:2023:2492).

This was surely the eagerly anticipated ruling by the Supreme Court, concluding that in the cases at hand, “taking into account the specific circumstances of the dispute“, there was not a failure of the claimant to provide evidence, so the gate to judicial estimation was opened. That conclusion was grounded in a systematic and teleological interpretation of article 101 TFEU and the need to ensure its effectiveness, which implies broadly that anyone harmed by an infringement of the prohibition of cartels and other anti-competitive agreements should be able to claim damages (par. 6. 22 of ES:TS:2023:2492), further enriched by two other arguments:

Temporal argument

When the suit was filed it was unclear if statistical analysis was valid/sufficient for calculating the cartel overcharge. It was repeated in several instances in the various judgments: “in view of the state of the matter and the litigation at the time it was submitted”” (par. 6.24 of ES:TS:2023:2492), “for the judgment on the sufficiency of the evidentiary effort, we must place ourselves at the time when the lawsuit was filed, so as not to fall into a retrospective bias” (par. 6.19 in fine of ES:TS:2023:2492).

Somehow the Supreme Court acknowledged the lack of sophistication of claimants at the early stages of the trucks cartel damages litigation. Although the courts rejected promptly the use of an extrapolation from statistics/metadata studies as a basis for the claimants’ damages petition, the suits were filed “when these judicial assessments denying the effectiveness of statistical methods to assess specific damages caused in the purchase of a vehicle affected by the cartel had not yet become widespread” (par. 6. 20 in fine of ES:TS:2023:2492). The Supreme Court also considered the notion that suits should be filed in court without delay: “at that time there was a general consensus on the duration of the time limit for bringing the action (one year, based on Art. 1968.2 of the Civil Code (hereinafter CC), counted from the publication of the summary of the Decision in the OJEU), which left little room for more elaborate expert reports” (par. 6. 21 in fine of ES:TS:2023:2492).

One of the justices deciding the cases had very recently reflected on the retrospective bias:

“Ex post, once an event has occurred, without realizing it, we tend to exaggerate its predictability ex ante. Uncertainties are invisible in retrospect.” (Ignacio Sancho “El arte de juzgar y las dificultades para encontrar la solución más justa” in Acto de Investidura del Grado de Doctor Honoris Causa, Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza 2022, 43).

In that contribution, Justice Sancho referred to such risk in assessing retrospectively the “inventive step” requirement in Patent law. Transferring his reasoning here, would suggest that if the expert activity is examined retrospectively, there could be a viewpoint that the inadequacy of an overcharge calculation based on a extrapolation from metadata studies was obvious when the lawsuit was filed (i.e., expert activity cannot be judged ex post facto, an effort must be made to put oneself in the shoes of an average expert with the knowledge that existed in the state of the art at the time of the filing of the lawsuit).

The reference to the “retrospective bias” is striking and does not seem to hold true: when the claims were filed it was clear that metadata studies were not apt for calculating the amount of the cartel overcharge in specific cases. The European Commission’s Practical Guide to the Quantification of Antitrust Harm was already five-years old, and it expressly cautioned against the use of such studies for harm calculation (par. 145, “These insights into the effects of cartels do not replace the quantification of the specific harm suffered by claimants in a particular case“). Further puzzling is the reference to the short limitation period (thought at that time), given the flexibility that Spanish law provides for its interruption which, arguably (and as done by other claimants), would allow a delay in the filing of claims in court until a proper expert report was prepared.

Economic argument

The costs of access to evidence (including documents in foreign languages) and experts needed to make an adequate calculation of the overcharge may be disproportionate in relation to the damages claimed (“Disproportion that would make the plaintiff’s legal claim clearly uneconomical“, par. 6.21 of ES:TS:2023:2492).

At first sight, given the modest amounts claimed, the resources available for hiring economic expertise for the calculation of the harm were rather limited. In half of the claims decided here the overcharge claimed was caused by the purchase of one cartelized truck, with the amounts claimed being well below €20.000. The Supreme Court extended this argument when the claimant was not a self-employed or a small firm, as in ES:TS:2023:2475 (EULEN, claiming damages for the acquisition of 17 trucks), or even “a company of certain relevance in the road transport sector, the court considers that this disproportion and the risk of the claim being uneconomical does not disappear” (Llácer y Navarro SL, claiming 108 trucks, ES:TS:2023:2480).

Looking at the limited sums at stake in most of these disputes, it is easy to agree with the view that, individually considered, most of the claimants in the cases before the Supreme Court would have found the costs of the elaboration of an adequate expert report as non-economical (see table 3, interest excluded, not in those amounts with *).

| Case nº | Number of Trucks | Amount claimed (€) | Amount awarded on appeal (€) | Amount awarded by the Supreme Court (€) |

| 923/23 | 1 | 17.358,46 | 3.985 | 3.985 |

| 924/23 | 1 | 6.694 | 1.834 | 1.834 |

| 925/23 | 3 | 40.325,92 | 9.735 | 9.735 |

| 926/23 | 1 | 18.068,14 | 4.582 | 4.582 |

| 927/23 | 17 | 151.946 | 105.546,92 | 36.182,31 |

| 928/23 | 1 | 12.270 | 0 | (4.086,88) |

| 939/23 | 1 | 14.314,90 | 0 | (4.057) |

| 940/23 | 1 | 13.605 | 1.450 | 1.450 |

| 941/23 | 2 | 24.005,04 | 8.704,57 | 8.704,57 |

| 942/23 | 2 | 72.814,11 * | 20.878,82 | 20.878,82 |

| 946/23 | 6 | 67.471,61* | 13.880,97 | 13.880,97 |

| 947/23 | 108 | 1.298.115,35 | 128.623,18 | 128.623,18 |

| 948/23 | 2 | 36.087,34* | 8.225 | 8.225 |

| 949/23 | 1 | 21.176,31 | 3.542,50 | 3.542,50 |

| 950/23 | 2 | 43.652,60 | 7.885,95 | 7.885,95 |

Table 3. Amounts claimed and awarded in cases decided by Supreme Court

In my opinion, this argument is more persuasive than the temporal argument, highlighting the need to protect claimants from the potential inefficiencies and limitations that might arise from the rules governing civil procedure in Spain. However, it ignores the fact that practical solutions were available to claimants and their lawyers (claim bundling and resources pooling). More problematic still is the fact that, contrary to the temporal argument, the economic argument would apply to more than half of the trucks cartel litigation in Spain, given that 60% of the claims involve the purchase of less than four trucks, with implications for other cases (namely, and probably with even more substance, to thousands of individual claimants in the automobile cartel).

Judicial estimation of the overcharge

To overcome the difficulties faced in the calculation of harm in antitrust damages litigation, the Directive recognizes the explicit power of courts to estimate the amount of harm (article 17.1 implemented as article 76.2 of Spanish Competition Act-this provision being applicable to the case in accordance to C-267/20 Volvo/DAF).

The Supreme Court considered that such power already existed previously in domestic law as an extension of the right to compensation in tort infringements (article 1902 of Spanish Civil Code) and as a requirement of the principle of indemnity of the aggrieved party (par. 6.15 and 6.24 of ES:TS:2023:2492).

In any case, given that the meta-data study presented by claimants has been considered unconvincing (both by the Courts of Appeal and the Supreme Court), the Supreme Court endorsed the judicial estimation of the overcharge at 5% of the price of the cartelised truck as minimum compensation. Only in one case (ES:TS:2023:2475), in which the claimants’ petition consisted also on the same extrapolation of metadata studies, the Supreme Court reduced to 5% a higher estimation of the harm by lower courts (15% in ES:JMBI:2019:547, confirmed by ES:APBI:2020:265, but with a dissenting opinion in the later precisely on this regard).

Future waves: above or below the floor of 5% of the price of the cartelised truck

The Supreme Court repeated several times that the judicial estimation of harm at 5% of the price of the cartelised truck is a “minimum”, in the context of the partial evidentiary value present in the cases that were decided now.

It is worth recalling that lower courts had arrived at that figure as the most “conservative” estimate of the overcharge taken from the “lower end” of the range of cartel overcharges on the basis of the OXERA report (Quantifying antitrust damages towards non-binding guidance for courts 2009), taking into account some qualitative features of the cartel (see eg, ES:JMV:2019:187, ES:JMV:2019:187, ES:JMV:2019:549, ES:APB:2020:2567, ES:APPO:2020:1243 and ES:APZ:2020:2008).

In endorsing the lower’s court judicial estimation of the overcharge in these cases, the Supreme Court introduced further ideas that may help in ascertaining the way ahead for the appeals that it will need to decide soon.

For the Supreme Court, the very description of the cartel that enabled the judicial presumption of harm, also indicate “that the harm was not insignificant or merely symbolic” (par. 6.24 of ES:TS:2023:2492). The floor of 5% set by the Courts of Appeal is accepted as a default quantification when none of the parties proved a different calculation. This calculation is further supported as being the award made by the CAT to large customers in its first judgment on the case ([2023] CAT 6).

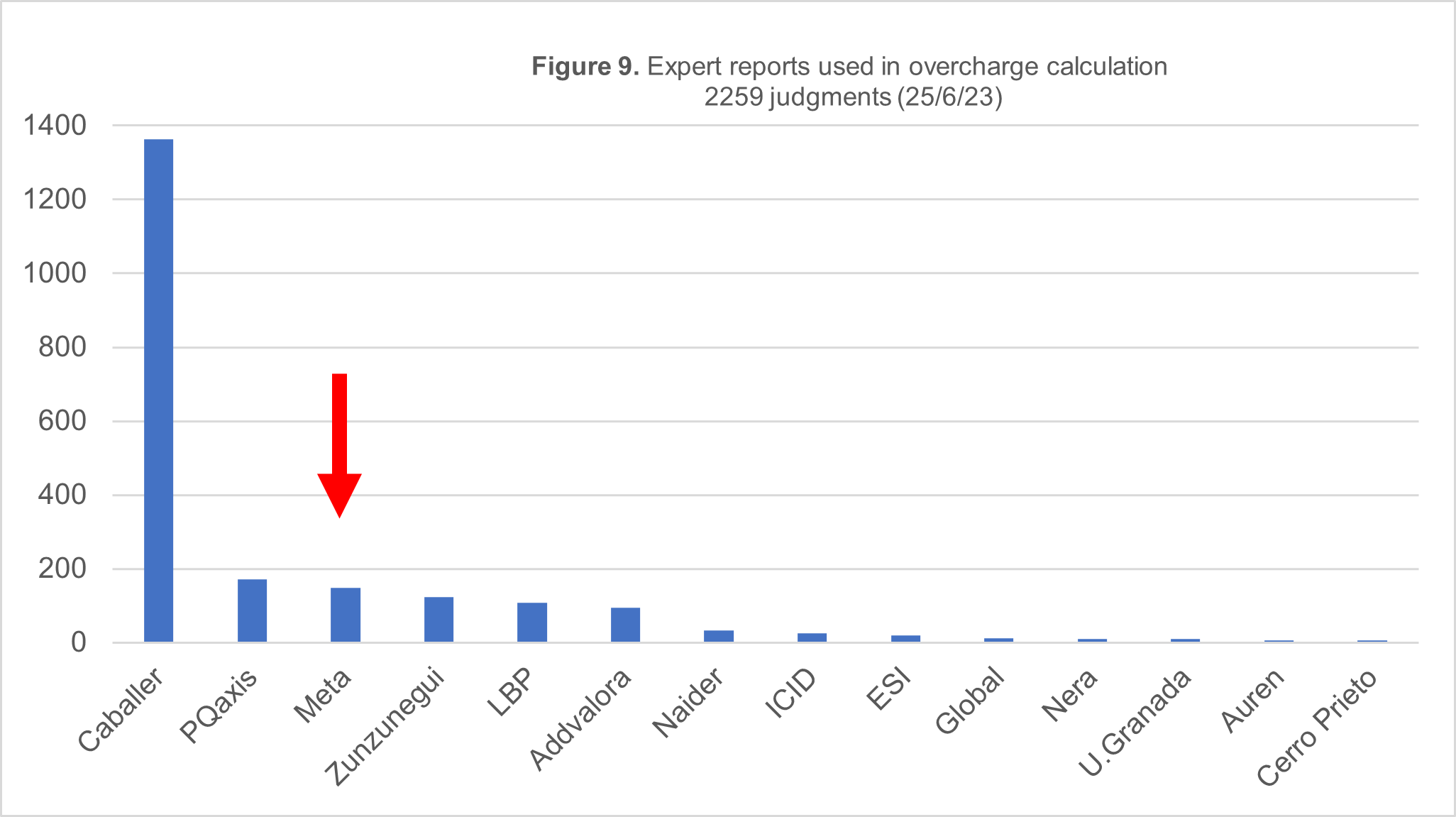

On the other hand, given that only 7% of Courts of Appeals’ judgments ruled on claims calculating the overcharge as the weighted average extracted from meta-studies (see Figure 9), it is still unknown how the Supreme Court will decide on appeals against judgments in which the claimants’ presented a proper expert report for the quantification of the cartel overcharge.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court judgments include a few reminders to its early jurisprudence (ES:TS:2013:5819) that may help to ascertain what it may do.

On one hand, the Supreme Court is clear in stating that a damages award exceeding the minimum of 5% is possible if the claimant proves that the overcharge was higher than that. On the other hand, it also considers the possibility that defendants could present an alternative overcharge calculation, lower than the minimum of 5% (par. 6.24 in fine of ES:TS:2023:2492).

In the only two cases in which the defendant (Volvo/Renault) had presented an expert report which tried to calculate the overcharge, the Court recalled that the possibility of showing an alternative harm calculation is also open to defendants (“the mere fact that an expert’s opinion on antitrust damages […] may result in the quantification of the damage at a very low value, or even show a value of 0, cannot by itself automatically disqualify its evidentiary value” par. 9. 23 ES:TS:2023:2479 and par 10.24 of ES:TS:2023:2480).

The Court explicitly affirmed that the quantification could be 0 but, in my opinion, this assertion is rather rhetorical, as it seems to contradict the Court’s own interpretation of how the trucks cartel operated and its effects on the market. Instead, it is more plausible that, using adequate and sufficient data (which KPMG did not use in the two cases referred, only utilizing prices for the 2003-2016 period), that a low overcharge was shown. For this purpose, the Court acknowledged that defendants’ data can be used in the calculation, considering that they “are relevant and adequate to be integrated in the analysis of the ham quantification“, as long as their selection was not flawed “by the application of biased criteria that could influence the results obtained from its analysis and affect its reliability” (par. 9.23 ES:TS:2023:2479 and par 10.24 of ES:TS:2023:2480).

In practice, moving away from the minimum floor will depend on the Courts’ assessment of the expert reports presented by the parties. Obviously, this idea is consistent with the general rules on the burden of proof in Civil Procedure, which also constitute a logical requirement to preserve and promote adequate investment by the parties in presenting adequate and reliable expert reports. In future appeals, however, the task of the Supreme Court is made more difficult due to some additional features present in the case law of Courts of appeals in the trucks cartel damages litigation.

It seems safe to assume that the Supreme Court will keep confirming the judgments of lower courts, as it has repeated in its judgments its unwillingness to review the assessment of the expert reports conducted by them unless there was “manifest error or arbitrariness” (par. 3.2 y 3 of ES:TS:2023:2478; par. 4.2. y 3 of ES:TS:2023:2479; par. 5.2 y 3 y 4 of ES:TS:2023:2480 and par. 2.2 a 2.6 of ES:TS:2023:2493), but a mere look to the diversity in decisions of the Courts of Appeals indicates that the Supreme Court cannot simply wash its hands of the matter.

Compared to the cases decided in the “first wave”, in other judgments to be reviewed in the future, Courts of Appeal had estimated overcharges higher than 5% of the purchase price of the truck (see figure 8). That is something that the Supreme Court explicitly contemplates, but what is relevant then is to analyze the reasoning that had led the lower courts to varying estimations of the harm.

Firstly, from what the Supreme Court has ruled, it can clearly be concluded that damages claims based on a extrapolation of metadata studies cannot exceed the floor of 5% (mainly ES:TS:2023:2475). This implies, that those judgments of Courts of Appeals that awarded more than that in those cases, if appealed, will be reduced (see, for example, ES:APC:2021:358, ES:APMA:2022:314, ES:APBA:2022:318, ES:APMA:2022:4005, ES:APA:2022:2475 and ES:APA:2022:2551).

Secondly, the fact that the Supreme Court set a minimum overcharge estimation for damages claims based on an extrapolation from metadata studies does not imply that the same estimation should apply in cases when the claims were based on proper expert reports. Therefore, as a matter of principle, and subject to the discussion below, it is possible that in other cases, if the expert report presented is deemed to have some evidentiary value, an overcharge above the 5% threshold may have been estimated.

In practice, that mean that there could reasonably exist diverse estimations and damages awards, and the Supreme Court may tolerate them, if the reasoning in lower courts’ judgments is not irrational or unjustified. Indeed, a similar situation occurred in the damages’ litigation in the envelopes’ cartel, where the Supreme Court implicitly approved a divergent assessment of the same expert report -and, subsequently, varying damages awards- by the Courts of Appeal of Madrid and Barcelona (cfr. ES:APM:2020:1 and ES:APB:2020:186). Nihil novum sub sole, and clear proof that the Supreme Court is not willing to become an additional instance for antitrust damages claims and that some level of disparity in the assessment of expert reports may be permissible.

Thirdly, the relative consensus of the lower courts and the Supreme Court on awarding a minimum estimated overcharge of 5% for damages claims based on an extrapolation from meta-studies simplifies that most Courts of Appeal have tended to project the same conservative estimation across the board to each and every case presented, independently of the different evidentiary value of the claimants’ reports. In fact, the 5% minimum estimation has become the average estimation, for every claim, as a sort of “consolation award” in 46% of the cases decided on appeal to date (all judgments in favor of claimants in Córdoba, Girona, Guadalajara, Lugo, Navarra, Orense, Pontevedra, Tarragona, Teruel, Toledo, Valencia, Vizcaya and Zamora).

At first glance, it could seem reasonable that the overcharge estimation would be equal for every claimant but, in my opinion, this understanding of the principle of equality is neither a requirement of the law nor coherent with incentivizing claimants’ efforts to present adequate evidence to the court. It rather promotes a mistaken idea of equality and propagates a false sense of legal certainty. Each claimant must reap the reward of what they have sown. This view (which I have defended in Almacén de Derecho 22/11/22 and 5/12/20) is not very original and several Courts of Appeal had introduced variations of the overcharge estimated depending on the evidentiary value of the report presented by each claimant (Almería, Barcelona, Burgos, Cádiz, A Coruña, Granada, La Rioja, Valladolid and Zaragoza).

Fourthly, at the same time, to make things even more difficult, some expert reports had been considered fully convincing by some lower courts but not by others (both at first instance and at the appeal level), due to mistakes and inaccuracies, which had led the later to reduce the damages awarded (claims based in the Addvalora, Caballer, LBP, Nera and PQAxis reports are prime examples). In that situation, it seems necessary that the Supreme Court will need to rule on these diverse assessments of the same expert reports by lower courts, because the divergences are based on a different interpretation of the requirement that, to be accepted and found convincing, any expert report quantifying the harm would need to provide “a reasonable and technically founded hypothesis based on verifiable and non-erroneous data“. In my view, it is not feasible that such contradictory assessment of the probatory effectiveness of the same expert valuation can coexist.

Interests

The Supreme Court judgments on this matter follow closely the case law of the CJEU that had interpreted the principle of effectiveness and the right to compensation of aggrieved parties as requiring that the payment of interest from the moment that the harm occurred is necessary as “a measure aimed at ensuring full compensation for the harm suffered by the victim of the infringing conduct of competition law, counteracting the effect of the passage of time between the time of the occurrence of the harm and the time at which the compensation for such harm is agreed” (par. 7.5 of ES:TS:2023:2492).

That being said, it is unclear yet what happens when the cartelised trucks were acquired through leasing and the impact that would have on the accrual of interest, as some Courts of Appeal had considered that in those cases harm was experienced with each of the installments paid (see, for example, ES:APZ:2021:1717 and ES:APGI:2022:1002) and not with the signature of the leasing contract, whilst other courts have come to the opposite view (ES:APB:2023:4207).

Conclusion

After the first fifteen judgments by the Spanish Supreme Court on damages claims in the trucks cartel, the law applicable to these claims and its interpretation have been clarified. As the judgments are final, several issues raised by Spanish trucks cartel damages litigation have been ruled upon by the Supreme Court and they are no longer subject to discussion.

First, in coherence with the design of the appeal procedure in Spanish civil procedure, the Supreme Court judgments show its unwillingness to become a “third instance”, as the judgments handed demonstrates a strong tendency of the top court to uphold the judgments appealed. Furthermore, last week reform of civil cassation will further expedite the processing of appeals before the Supreme Court, relieving the top Court from the obligation to rule on all appeals.

Second, endorsing the unanimous understanding by all Court of Appeals in over 2000 judgments, the Supreme Court has ruled that the trucks cartel had caused damage to truck purchasers. The existence of an overcharge can be presumed from the narrative of the cartel in the Decision of the European Commission. Those aggrieved by the trucks cartel are entitled to compensation of the overcharge paid and interest accruing from the moment of purchase.

Third, when claimants file their suits in court, they should provide a quantification of the overcharge but, in assessing the probatory value of their expert reports, the courts should pay attention to the specific circumstances of each dispute. In this first batch of cases decided by the Supreme Court, damages petitioned were calculated through an extrapolation from statistics and metadata studies on cartel overcharges. Those calculations were found to be unconvincing by lower courts and by the Supreme Court. Still, the Supreme Court has considered that, given the circumstances, even such calculation has some partial probatory value and that courts are enabled to undertake an estimation of the overcharge.

In the cases decided by the Supreme Court, lower courts had conservatively estimated the overcharge at 5% of the purchase price of the trucks. The Supreme Court confirmed the estimation of the lower courts, stressing that the level of 5% is the “minimum” damages award. As a guideline for future cases, it acknowledges that there may be awards above and below that minimum depending on the proof provided by the parties. Pending litigation on the trucks cartel damages in Spain will focus on the quantification of the overcharge along the lines drawn already by the Supreme Court.

_________

* The contributor serves as academic consultant of CCS Abogados, a law firm representing claimants in truck cartel damages actions in Spain, but none of the decided in the judgments here in commented. The author wishes to thank Margarita Alonso-Graña, Lluis Bielsa, Javier Borque, Jaime Concheiro, Juan De la Cruz, Pablo Fuentes, Rafael Fuentes, Javier García de la Serrana, Pedro González, Manuel Martín, Sergio Mencher, Pedro Miralles, Manuel Sánchez and Almudena Vázquez, and some judges for sharing judgments which had not been included yet in the official database CENDOJ. Comments by Miguel S. Ferro, Barry J. Rodger and Ainhoa Veiga are gratefully acknowledged.