The Reversal in the Burden of Digital Regulation

To address this shift, legislators in different jurisdictions are adopting digital regulations across various fields, notably to curb digital market power or content moderation. To address this shift, legislators in different jurisdictions are adopting digital regulations across various fields, notably to curb digital market power or content moderation.

The striking difference between these rules and those set out in the past lies in the reversal of the burden of production. The burden of production is distinct from the burden to persuade and refers to the initial responsibility for producing evidence. The concept does not care how persuasive an argument is or what evidence the regulator might find. In this post, I explore how the concept of burden of production can be used to force platform power from its private cast. By doing so, I tested its ability to act as a magic bullet to counteract information asymmetry and limited observability. A fully-fledged discussion of my findings may be found in my recent working paper, available on SSRN

.

The burden of production in different regulatory regimes

A fundamental shift illustrates the current digital landscape. The public and private spheres are now merged, both on a collective and individual level. Collectively, it means that platform power has been untouched by regulatory (and public ) intervention until very recently. The reasoning behind the disintegration in liability suggests that economic equilibrium and the realities of the market drive digital platforms to success or failure. Users can crown or depose market leaders by interacting with digital platforms. These platforms are legitimate because they have a ‘private source’ of accountability. Users may abandon a platform in response to its transgressions of mainstream values. In fact, the exodus

from X to Bluesky in the millions demonstrates that this might be the case.

However, digital spaces are not completely private in nature. They have the ability to appoint market outcomes according to their liking. This stems from the misallocations of liability across the internet. They do this by substituting their rule-making and standards-setting capabilities with public regulatory powers in their digital ecosystems. The consequences of those decisions touch upon economics in framing competition in an oligopolistic fashion as much as they relate to the interference and interpretation of fundamental rights, notably in relation to freedom of expression and information or the right to the protection of personal data.Deliberately conflating public and private powers must trigger legal consequences for those abetting the confusion. As they did with utilities-based regulation, policymakers are progressively designing self-regulation-inspired instruments to capture private platform power. By borrowing from the rationale underlying the precautionary principle, regulators are reversing ‘walled-off’ competitive dynamics towards the public sphere.

Capturing digital platform power is not performed as an exception but by default. Digital platforms are required to explain their actions before they can be excused from liability. This is not the best way to make the logic real. This mechanism entails resource-intensiveness and an initial configuration of forces in a litigation-driven scenario.

By contrast, most regulators have introduced their legal instruments by relying on the burden of production. According to US precedents, the burden of proof is a reference to the party that has the responsibility to produce evidence at the beginning of an iterative procedure. The burden is against the party who wishes to change a legal conclusion. In that particular context, the burden of production and the burden of persuasion are set apart as two completely different notions playing different roles in iterative processes.

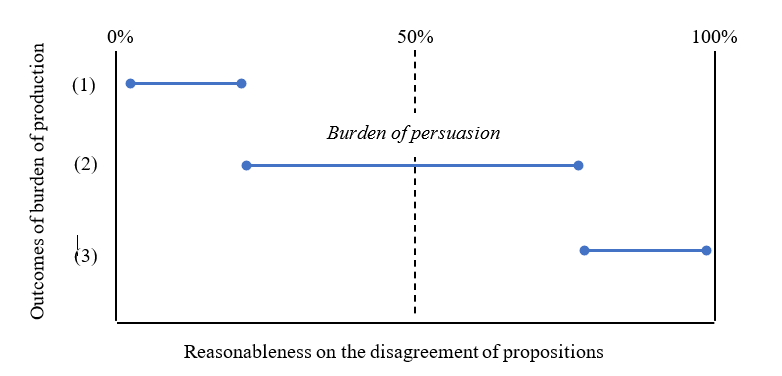

Burdens of production act as sediments to the parties’ burdens of persuasion. Persuading someone on the basis of evidence is different from producing that evidence. These are two distinct tasks that may be assigned differently to each party. The burden of proof is the obligation on a party to provide information or evidence in order to reach a specific legal conclusion. The burden of production stems from the need to assign burdens based on issues such as costs for the parties and fairness. In litigation, for example, burdens are relevant because they show whether the parties have a reasonable disagreement about the subject. This disagreement will be carried over to be the main point of contention around which the burden will be centered in the proceedings before a court. The regulator must prioritize the instances in which it will use its punitive or non-punitive tools, to influence the target’s behavior towards the regulation. The burden of production determines the exercise. If the target shows that there is no need to have a discussion with the regulator, because compliance is obvious and does not cause further controversy, it is pointless to open a new investigation. The burden of production acts, in these instances, as a means of screening cases, just as the figure below demonstrates:

Different scenarios showing the interplay between the burdens of production and persuasion.

The burdens of production, which can be in the form of disclosure or sharing of information from the regulated entity, predetermines the burdens of persuasion. This is to the extent that less reasonable arguments presented (Scenario 1) by the regulated entities will not serve as a basis for any dialogue or contention with regulator. The parties’ disagreements are not reasonable and as such the target does meet the burden of producing. This automatically means that legal consequences are not contested by the undertaking. In these cases, the regulator’s expenditure would be inefficient because the violations of law are obvious. The middle ground cases, where the party is able to surpass the standard of scenario 1, but not reach scenario 3 (in reality, scenario 2), are the ones that create uncertainty about the legal consequences. The parties must iterate so that the regulators and courts can decide which legal consequences are appropriate. The burden of proof has been removed, so the parties will compete to prove their case in accordance with the standard set by the law. This may lead to a reasonable disagreement between the two parties. The EU’s Digital Markets Act (

), UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act(DMCC)

and Japan’s Smartphone Act

all tackle digital market power by introducing hybrid enforcement where the need to disclose information does not change. Informational imbalance exists between the digital platform’s control over its ecosystem, and the rules vis-à-vis regulator. The regulation’s recipients must therefore demonstrate that they are in compliance with the regulations by engaging them on merits, and doing so in two fundamental ways. They reveal information that may have been hidden from the regulator. Second, they impose an enhanced obligation upon the targets to reverse the factual presumption that they do not comply with the legal requirements of the regulations.

Before the disclosure of information, the regulator decides whether those statements are entirely credible or whether it should pursue any further enforcement action. The regulator does not bear the burden of proof because these declarations have no legal effect on it. In fact, it is at this point that the burdens of production for digital regulation are most similar to those in US litigation. Burdens for production do not act as a burden of proof that is shifted between the parties. They predetermine the configurations of the parties. In turn, the regulator picks its battles when its targeted intervention may bring the most impact to meeting the broader objectives of the regulation, especially in those cases where undertakings overcome the burden of production and enforcement must be nailed down via the burden of persuasion.

Consequences: information asymmetries and limited observabilityIntroducing the burden of production as a means to disintermediate information asymmetries between private regulatory powers and public regulators may, in fact, generate synergies to overcome the black-box rationale. Self-regulated entities are more likely to oppose any form of interference in the absence of regulation. This is because they have better enforcement mechanisms and more knowledge than public authorities. They argue that de-regulation is essential to ensuring the best market outcomes. Information asymmetries can occur if private parties are allowed to hold more information than public regulators. The argument is that information asymmetries lead to misallocations of resources and transactional risks for regulators. This creates informational advantages and increases adaptability. By generating these informational benefits, the regulator has a preliminary amount of information to understand the true nature of the targets’ dynamics. On the other hand, adaptability benefits allow the regulator and target to exchange views on compliance without the automatic and direct application of a control-and-command regulatory structure. Instead, tit-for-tat iterations take place as an ongoing process where regulators and addressees engage in an experimental learning process adapted to strategic uncertainty, bearing in mind the dynamic nature of information asymmetries.Notwithstanding, for information disclosures to be effective, much more is needed than simply imposing the legal requirement via regulation. In a managerial sense, the undertakings should assign the responsibility of disclosing information to those who have the most knowledge about the risks and the potential control methods. In order to be feasible, it has to be less expensive and more effective to comply to the mandatory disclosure requirements rather than be subjected to regulatory standards or sanctions. The exchange of information should be more beneficial than the costs associated with not doing so. The table below shows the regulators’ potential reactions to their lack of compliance with the mandated disclosure requirements:

Digital Markets Act

Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act

Smartphone Act

Punitive responses

–

| Penalties for failure to comply with investigative requirements (SS87(1)(a)). | Fines (Article 53). | Non-puni The table below shows the regulators’ potential reactions to their lack of compliance with the mandated disclosure requirements: | |

| Digital Markets Act | Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act | Smartphone Act | |

| Punitive responses | – | Penalties for failure to comply with investigative requirements (SS87(1)(a)). |

Fines (Article 53).

Non-punitive responses

Requests of information (Article 21); Power to carry out interviews and take statements (Article 22); and Powers to conduct inspections (Article 23).

Power to require information (SS69); Power of access (SS71); Power to interview (SS72); Power to enter business premises with and without a warrant (SS74 and 75).

In this context, both the UK’s and Japanese approaches to addressing the force of the burden of production are much more prone to aligning the undertaking’s incentives to submit complete information to their regulators. The DMCC Act and the Smartphone Act allow the enforcer to sanction the target for refusing to meet the burden without needing to prove any other substantive violation. On the contrary, the DMA is not sufficiently equipped to address this risk as a standalone infringement with punitive mechanisms to incentivise undertakings to engage in full disclosure of their activities by providing the most accurate and appropriate depiction of their business models and functioning.

The burden of production is not a silver bullet mechanism ending with all enforcement problems relating to the original information asymmetries justifying the adoption of the regulation. There are many information asymmetries. This leads to a variety of enforcement challenges. The goal of narrowing information asymmetries should not be the end in itself. It is a tool to achieve a goal. This is a way to make a target more visible in a specific context. The burden of production does not always lead to positive outcomes. Information does not always translate into increased observability. Transparency does not always imply scrutiny by a particular forum. This is nothing especially new for regulators: targets of the regulation will be prone to insulating certain tenets of the regulation from transparency, which impacts most of their functioning.

01001010Key takeaways01001010Disintermediating private regulatory power is no small feat to achieve. Digital regulation that addresses market power in various jurisdictions proposes an updated version of the burden allocation to tackle this challenge. Legislators have created a new artifact instead of imposing the usual burdens of proof on targets: the reversal in the burden of production. The difference is immediately apparent. The burdens of production are not meant to reach a conclusion through a dialectical exchange, but rather to set the terms for the discussion, asking if the parties should engage in a dialogue with each other to persuade them. The paper also shows that a burden of production does not necessarily mean that asymmetries in information will disappear from a regulatory perspective. The burden of production, on the other hand, does not undermine or promote a regulation’s ability to hold platforms accountable. It is a neutral tool that can provoke either passiveness or reactiveness on the part of the target. It is not a good idea to reduce a regulation’s efficiency to this aspect. It does not align with the incentives for targets to engage in a triangular, dialectical, and iterative exchange with public regulators.