The Effects Of Using New Tax Revenue To Shore Up Medicare’s Finances

How could new tax revenues ease Medicare’s substantial financial pressures? And how would those tax hikes affect federal revenues and the distribution of tax burdens across income groups? A new joint report from the Urban Institute’s Tax Policy Center and Health Policy Center examines the pros and cons of several plans to increase taxes to support the program.

Due to increasing costs per enrollee and the aging of the population, Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund is expected to be depleted in about five years. Over the next 20 years, total annual Medicare spending, including payments for physician services and prescription drugs, is projected to increase by about two percentage points of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), or roughly $500 billion in today’s dollars.

Since cost containment needs to be implemented gradually and can take years to yield results, Congress may have to address at least some of the Medicare’s financial shortfall with additional tax revenues. The financing gap just for HI (projected spending in excess of projected revenues) over the next 10 years will be $390 billion.

Our report analyzes 12 options for raising tax revenues for Medicare. Here are results for five of them.

Raise Medicare payroll tax rates. Increasing the payroll tax rate by one percentage point would be administratively simple and raise more than $1 trillion over the next ten years. That’s more than sufficient to fill the HI’s ten-year financing gap, though not enough to cover the projected long-term growth in Medicare’s overall costs.

The additional revenues would automatically be credited to the trust fund. Raising rates equally on all workers would be consistent with the program’s original intent of all workers paying at least some amount for their future Medicare benefits.

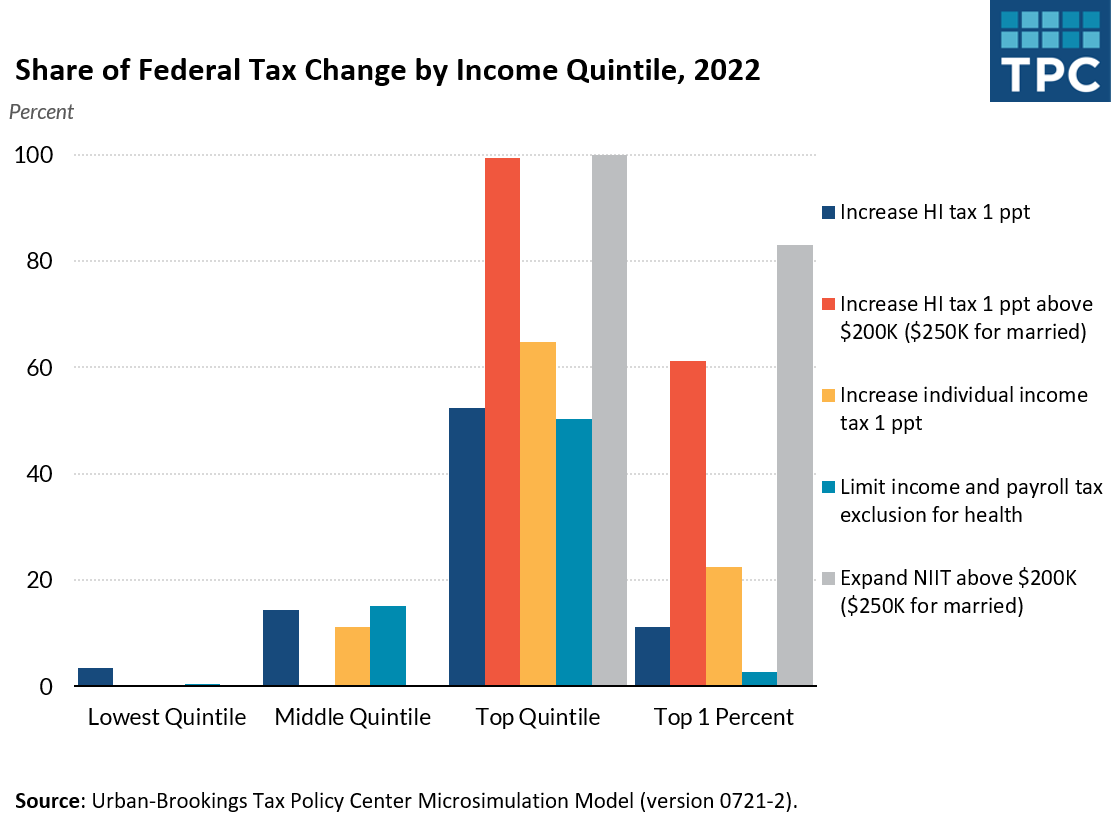

However, the option is less progressive than others since the lowest-income families would pay a larger share of the tax increase while the highest-income 20 percent of households would pay a smaller share, relative to other options.

In addition, raising payroll tax rates can increase incentives to shift compensation to tax-free benefits such as health insurance. It may also reduce incentives to work, though these tax changes may play only a modest role in that decision.

Raise the Medicare payroll tax rate only on workers with earnings in excess of $200,000 ($250,000 for married households). This alternative is also simple to implement and significantly more progressive. But it raises only about one-fifth as much revenue, highlighting the tradeoff between larger revenue increases and shielding most families from tax increases.

Increase individual income tax rates by one percentage point. This option also would raise about $1 trillion over ten years. Because it applies to capital income as well as wages and leaves a significant amount of initial income untaxed due to the standard deduction, this option is more progressive than raising Medicare payroll tax rates.

However, crediting the new revenue to the HI trust fund would require additional congressional action. It also would increase the complexity of the Medicare system. And raising income taxes can reduce incentives to work and save, increase incentives to shift to untaxed compensation and encourage spending on deductible expenses such as mortgage interest.

Limit the tax exclusion for employer-paid health insurance. The cost of this coverage is exempt from federal income and payroll taxes despite being a form of compensation. Limiting this tax exclusion at the 75th percentile of premiums could raise nearly $380 billion, and potentially reduces health care costs by reducing incentives to buy expensive insurance.

However, most of the revenue gain would not go to the HI trust fund without additional congressional action. And, absent other adjustments, the shift could encourage employers to offer health plans with cost-sharing that is too high for low-wage workers.

Expand the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). This 3.8 percent tax, adopted as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act, is imposed on certain investment and business income of high-income taxpayers. Similarly, high-income workers and self-employed business owners pay a 3.8 percent Medicare tax on their wages and related earnings. However, some income of owners of certain kinds of businesses is exempt from both the Medicare tax and the NIIT. Expanding the NIIT to cover all business income not subject to Medicare taxes above $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for joint filers would raise nearly $240 billion. It also would be very progressive since more than 80 percent of the tax increase would be paid by families in the top one percent of income.

This option would treat all high-income families the same regardless of how they receive their income and reduce distortions in choice of business organization and the way businesses pay their owners. However, Congress would have to credit the income to the HI trust fund. And, like any tax on capital, it could reduce incentives to invest.

These are only a few of the options analyzed in the report. But they illustrate that, when it comes time to raise revenues for Medicare, policy makers will need to consider the magnitude and distributional impacts of various options. And they will need to weigh tradeoffs between simplicity, equity, and efficiency.