The court is poised to set jurisprudence on race for generations — and not just in affirmative action

SCOTUS FOCUS

on Oct 30, 2022

at 7:00 pm

Last term at the Supreme Court teemed with culture-war issues: guns, religion, climate change, COVID vaccines, and of course abortion.

This term will be defined largely by just one: race.

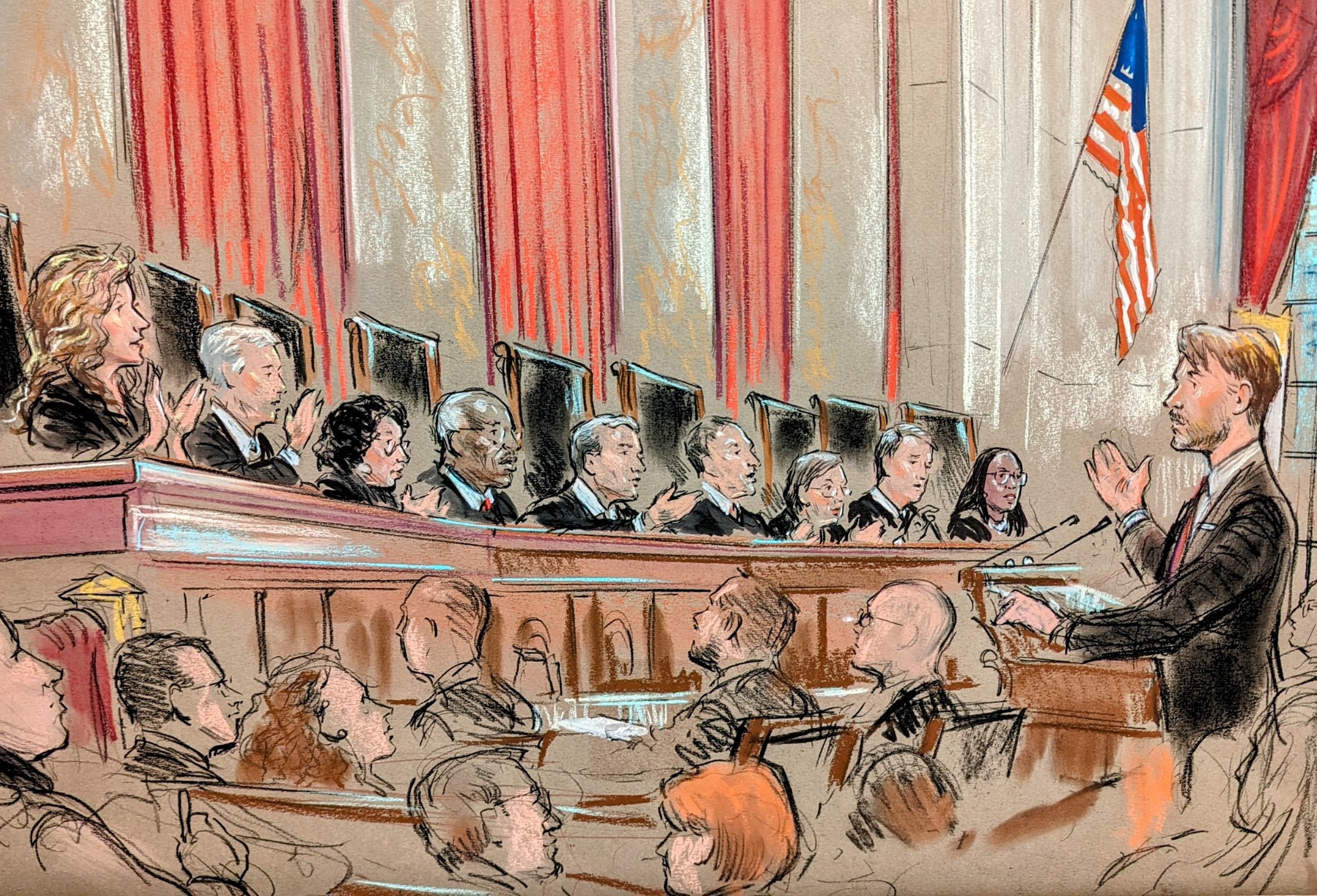

Most prominently, the justices will decide a pair of cases that test the future of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education. Oral arguments in those cases are scheduled for Monday in a Halloween doubleheader that likely will stretch for more than four hours.

But race pervades the rest of the court’s docket as well. Beyond affirmative action, two major cases challenge efforts by Congress to remedy discrimination against historically oppressed groups. And in several other high-profile disputes that are nominally about other constitutional questions, race lurks just below the surface.

This is all playing out as the Court’s newest justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson, makes history as the first Black woman to serve among the nine—and as the Court’s other Black justice, Clarence Thomas, is emerging as the leader of the court’s conservative majority. That Jackson and Thomas diverge sharply in their approaches to questions of race is perhaps emblematic of the country’s continued divisions over America’s original sin.

Start with affirmative action. In 1978, 2003, and 2016, the court affirmed that universities may consider applicants’ race as part of an effort to foster diversity on campus. (Notably, this diversity interest is the only permissible rationale for affirmative action under current precedent; the court has never endorsed an alternative justification that many find more cogent: the interest in rectifying past discrimination.) Yet the court’s decisions in this area reveal some justices’ obvious discomfort with race-conscious policies, even as they tentatively permitted such policies as part of a “holistic” admissions program. Most famously (or infamously), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s landmark 2003 opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger declared an expectation that affirmative action would no longer be necessary in 25 years — a self-imposed expiration date that would be unheard of in any other area of constitutional law.

It has been 19 years since Grutter, not 25, but opponents of affirmative action are now urging a newly conservative Supreme Court to hold that race-conscious admissions programs discriminate against white and Asian American students. In cases involving the University of North Carolina and Harvard, they argue that the 14th Amendment (which applies to public universities) and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (which applies to private universities that take federal funding) bar affirmative action altogether.

In the briefings from the universities and their supporters, a certain tension emerges. They emphasize that race is merely one “limited” factor within comprehensive admissions programs that evaluate applicants based on innumerable variables and seek to promote diversity in all sorts of ways. A student’s race, they suggest, is rarely or never decisive in an admission decision. At the same time, they warn that eliminating universities’ ability to use this limited factor would have sweeping and devastating effects. Racial diversity at many of the nation’s most selective schools, they say, would plummet.

Opponents of affirmative action also face potential inconsistencies. They spill buckets of ink on the premise, or promise, of a colorblind Constitution. But the initial Constitution was of course not colorblind: It protected slavery. And the challengers’ view of the 14th Amendment as enshrining a neutral, colorblind equality principle is contested by historians and legal scholars who argue that the 14th Amendment (as well as the 13th and 15th) were effectively affirmative-action amendments. They were not intended to be race-neutral; they were designed to lift up Black Americans.

Jackson emphatically voiced this view of the 14th Amendment earlier this month, in just her second day hearing arguments as a justice. The case was Merrill v. Milligan, which asks whether Alabama violated the Voting Rights Act by gerrymandering Black voters in a way that minimizes their ability to elect their chosen candidates. At stake is the continuing vitality of the Voting Rights Act itself, which Congress passed in 1965 (and repeatedly reauthorized) as a remedy for the history of racist voter-suppression practices.

On Nov. 9, another remedial statute is at risk. In Haaland v. Brackeen, the court will hear a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act, which Congress passed in 1978 to respond to disproportionately high rates of Native American children being removed from their parents and placed with white adoptive families. After finding that state child-welfare agencies frequently displayed bias against Native cultures, Congress expanded the authority of tribal governments to make decisions about the placement of Native children in custody cases, foster care, and adoption. The law also created a preference for Native children to be placed with other Native families if they are removed from their homes.

In Haaland, three white couples who sought to adopt Native children are challenging the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act. In an echo of the affirmative-action cases, the couples say the law discriminates against them on the basis of race.

Other cases that don’t directly deal with race are far from race-neutral. Take Moore v. Harper, the term’s other blockbuster after the affirmative-action challenges. In it, the court will decide whether the Constitution gives state legislatures the power to make rules for federal elections without any supervision from state courts. The case arises from a dispute over political, not racial, gerrymandering. But if the justices endorse the “independent state legislature” theory, state legislatures will gain new power to enact new voting restrictions — many of which disproportionately affect people of color.

And then there is 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis. That’s the case of a Colorado website designer who doesn’t want to create wedding websites for same-sex couples, despite a state law that forbids businesses from discriminating against LGBTQ people. The designer says she is entitled to a First Amendment exemption from the law, lest she be compelled to endorse same-sex marriage. One question is almost guaranteed to come up at the Dec. 5 argument: What if, instead of same-sex marriage, the plaintiff opposed interracial marriage? Would she still be entitled to a First Amendment exemption?

In 2020, in a case raising an analogous issue in the religious-freedom context, Justice Elena Kagan commented with characteristic understatement, “Race is sui generis in our society in all kinds of ways.” But the court has never articulated a doctrinal reason why a purported First Amendment right to discriminate on the basis of race should be treated differently. Soon, it might have to.

This column was originally published on Oct. 27 in National Journal and is owned by and licensed from National Journal Group LLC.