The 529 Plan Conundrum | Pennsylvania Family Law

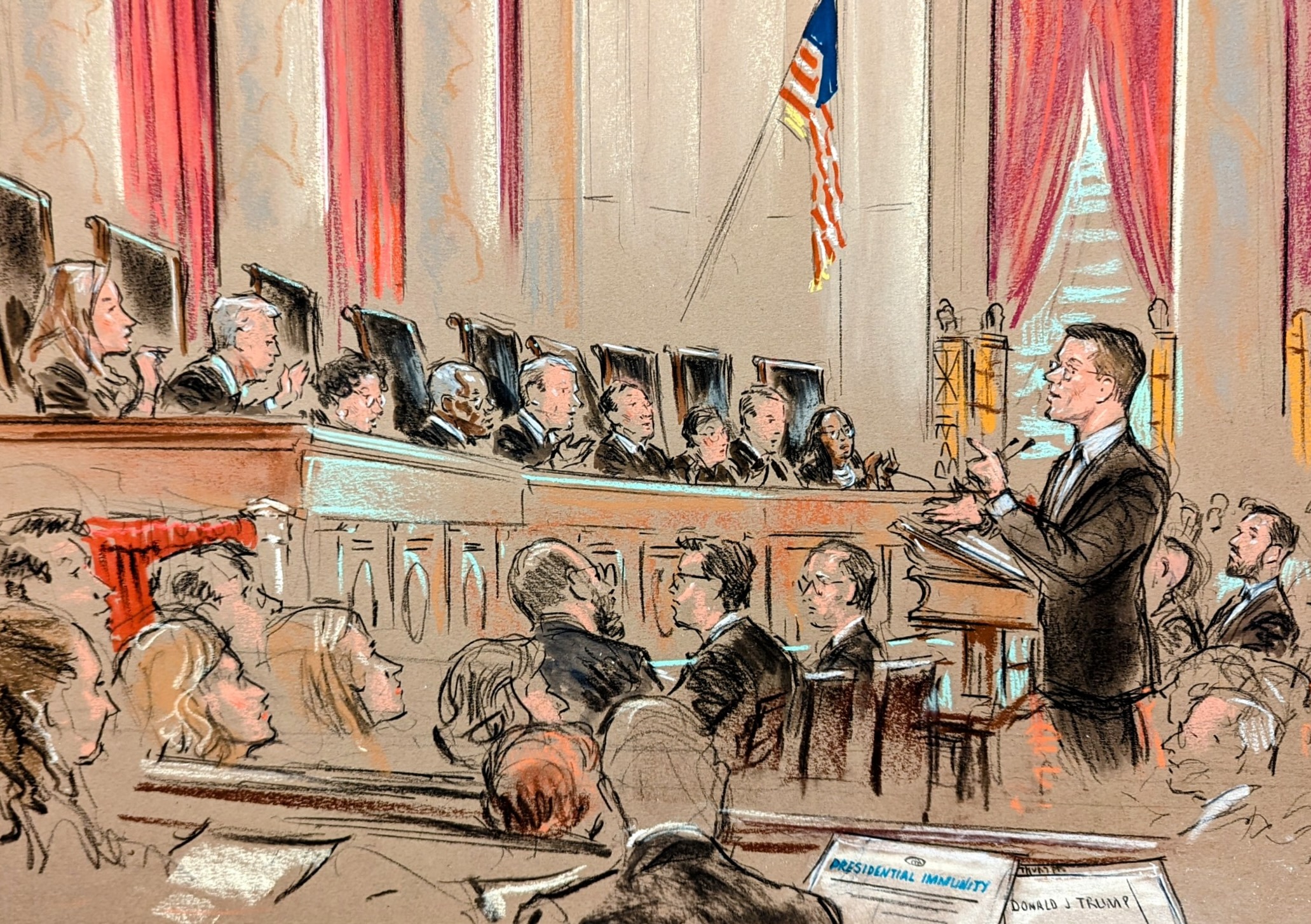

We are entering a strange new world where there are evolving questions about whether assets and rights are federally regulated or state managed. Some of this is traceable to Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, the case that overturned Roe v. Wade. These are reproductive rights cases but the Supreme Court said in Dobbs that these rights were to be state regulated. Last month the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether Texas has the right to regulate a medication which has the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine.

Today we look at and older and increasingly strange set of inconsistencies between federal and state regulation. The subject is a bank or brokerage account. In 1996 Congress passed 26 USC Section 529 to encourage college savings plans. The idea was that money could be put into accounts where there were tax advantages shielding income from federal income taxes provided that the money is deployed to pay qualified educational expenses.

The trouble is that there are no federal accounts. Rather, if you are a customer of Cincinnati’s Fidelity Investments and you call them to open a Section 529 Account, your account is part of New Hampshire’s plans. If Vanguard is the company you call, you may be opening a Nevada managed account even though your residence is in Paoli, PA. a mile away from Vanguard’s headquarters.

Section 529 plans provide some advantages both in taxability and flexibility. Unlike UTMA accounts where a completed gift is made when the account is open, a 529 account remains the property of the person who created it; it’s just that if the owner deploys its assets except for qualifying educational expenses, the tax advantages are lost. The advantage is that if the owner needs the money, he can get to it.

Under Pennsylvania law, these accounts are marital property and subject to distribution in divorce. Most couples going through divorce typically adopt agreements that state the owner of the account will maintain it and not take any withdrawals except for qualifying educational expenses. Unfortunately, the law does not permit these accounts to be held jointly.

When you open a 529 Plan, you are typically invited to name a successor owner, should you become incapacitated or die. Herein lies a problem. That successor is not bound by your agreement with your spouse unless that person somehow is made a party to the agreement. As one commentator put it in 2022: “[C]onsider the unfortunate situation where the money you intended to be spent on your child’s or grandchild’s college education was instead used by your successor as the down payment on a West Palm Beach condo.” The writer’s admonition: choose your successor with care.

The successor account owner also has the right to change the beneficiary. A stepparent might use your 529 plan to fund his or her own children’s college education, as opposed to your own. The consensus appears to be that if a successor is named, the account is not an estate asset but passes to the successor much as a joint account or transfer on death (TOD) account would. Realize that just how that process works is likely governed by the law of New Hampshire or Nevada or wherever the account is legally managed.

Of course, the whole point of Section 529 accounts is to use them to pay for those qualifying expenses so it is quite rare for a successor beneficiary to ever have rights to access an account. But death and legal incapacity (i.e., incompetency) do create risk of the West Palm condo.

Is there a reasonable remedy here that avoids the West Palm risk? Perhaps. The successor to a 529 account might be a trust crafted to require the very things the parties profess to want in their agreement. But then someone needs to draft a trust and identity an appropriate trustee. And for folks ages 40-50, the likelihood of death during any one year is 3 to 5/10s of 1% for men and half of that for women. A trust is a useful conservative approach but given the small likelihood of death or mental disability, the cost to create the trust may eclipse the risk.