Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSA) Are a Huge Success in Canada

For most Americans, saving is a taxing experience. The most readily available option is to put money away in a savings or brokerage account and then face taxes on any interest, dividends, or capital gains received. Another option is to navigate a convoluted system of tax-advantaged accounts narrowly specified for limited uses, such as 401(k)s and IRAs for retirement, health savings accounts (HSAs) for qualified medical expenses, 529s for qualified education expenses, and the new Secure 2.0 provisions allowing employers to offer pension-linked emergency savings accounts under certain conditions.

Our neighbors to the north have found a better solution—and U.S. lawmakers should take note. Since they began in 2009, Canada’s tax-free savings accounts (TFSAs) have provided Canadians a simple option to save taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

-free without strings attached. TFSAs are a type of universal savings account (USA), in which individuals 18 or older can make contributions on an after-tax basis (i.e., non-deductible), earnings grow tax-free, and withdrawals can be made for any reason without triggering additional taxes or penalties. The annual contribution limit in 2024 is CAD 7,000 (about USD 5,200), and it is indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

. Any unused contribution allowance (“room”) is carried forward to the next year, and any money withdrawn in the current year further adds to the subsequent year’s contribution room.

While Canada also offers tax-preferred retirement account options similar to ours—registered pension plans (RPPs) that are similar to 401(k)s, and registered retirement savings plans (RRSPs) that are similar to traditional (deductible) IRAs—Canadians have quickly made TFSAs their preferred saving vehicle. By 2013, the share of Canadian families contributing to TFSAs and the amount of TFSA contributions exceeded that of either RRSPs or RPPs, and by 2020 TFSA contributions exceeded that of RRSPs and RPPs combined.

According to survey data from 2022, 58 percent of Canada’s adult population has a TFSA versus 46 percent with a retirement plan. The gap is particularly wide for young adults, with 51 percent of people ages 18 to 34 owning a TFSA versus 38 percent owning a retirement plan, indicating that a major appeal of TFSAs is the immediate and unrestricted access to funds for various purposes besides retirement. When asked which goals are most important for saving and investing, the most common responses were to “retire comfortably” and “build a safety net,” the latter of which is better addressed with TFSAs than retirement accounts.

A study based on 2015 data shows that low-income households in particular are much more likely to contribute to TFSAs than tax-preferred retirement accounts. Among households earning under CAD 80,000, about 34 percent contributed to a TFSA, substantially higher than the 20 percent who contributed to a retirement plan or 18 percent who contributed to a pension plan. The contrast is even more stark for lower income groups (e.g., among people earning less than CAD 10,000), about 15 percent contributed to a TFSA while just 3 percent contributed to a retirement plan and 1 percent to a pension plan.

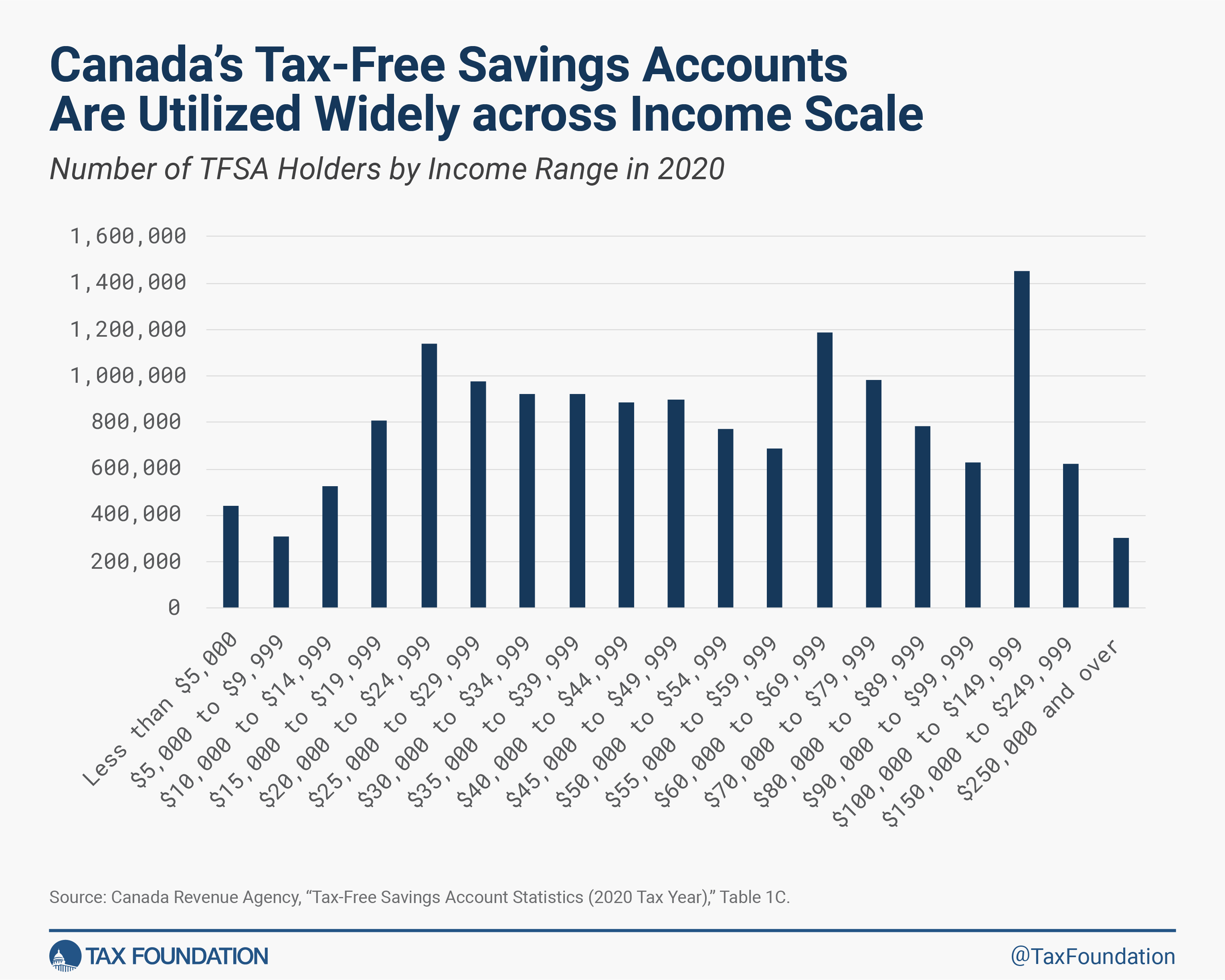

The latest statistics show Canadians across the income spectrum use TFSAs extensively. In 2020, 16.1 million Canadians owned a TFSA, more than half of the adult population (54 percent of the tax-filing population, which closely matches the adult population). Of the 16.1 million adults with a TFSA, 3.2 million earned less than CAD 25,000, indicating about one-third of this low-income group owned a TFSA. Among adults earning between CAD 25,000 and CAD 40,000, about half own a TFSA. The share of adults with a TFSA rises with income: more than 3 out of 4 adults earning at least CAD 150,000 own a TFSA.

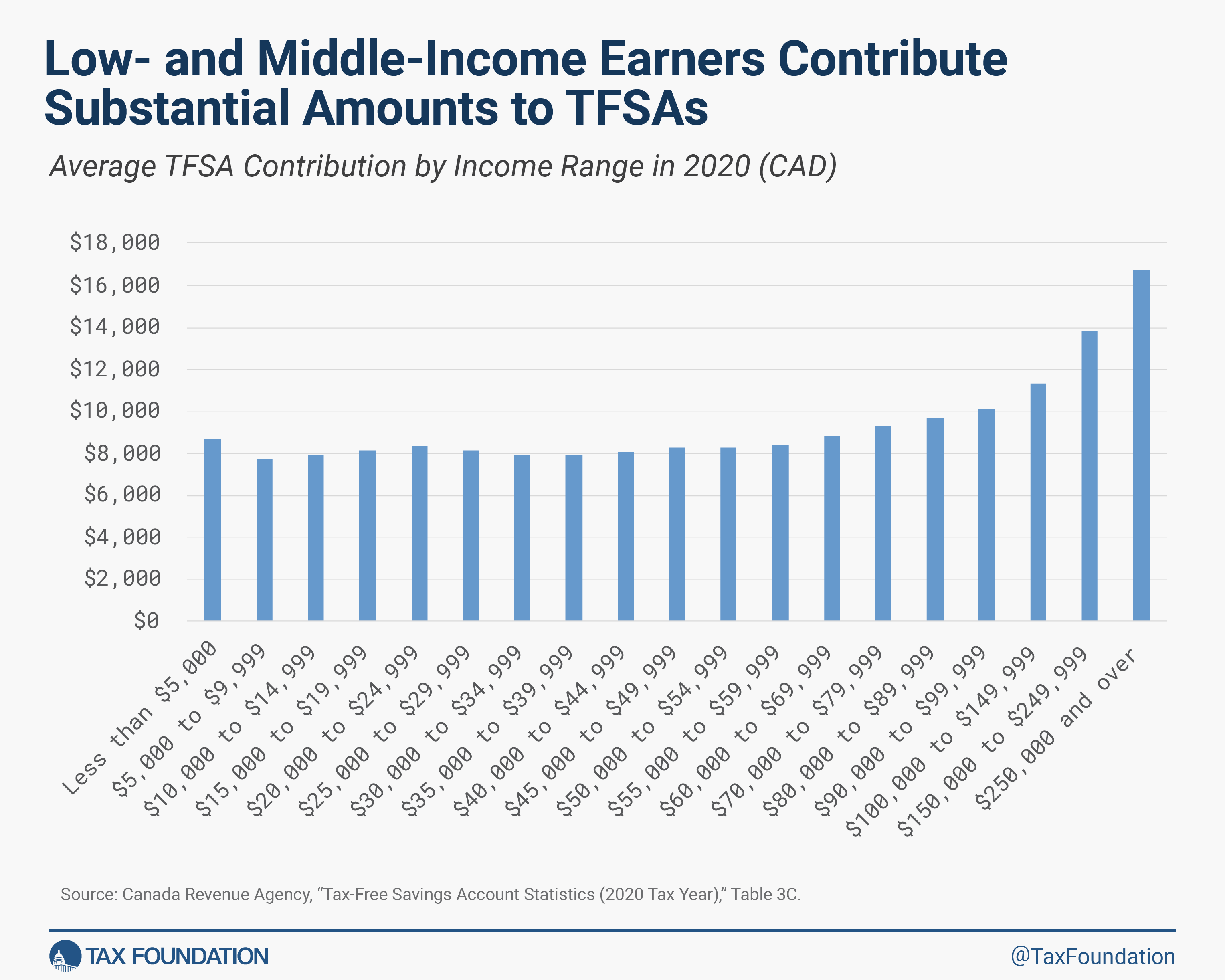

The average TFSA contribution is remarkably flat across the income scale but does rise for people earning more than about CAD 60,000. The average contribution is about CAD 8,000 for each income group earning below CAD 60,000 and rises to about CAD 17,000 for people earning more than CAD 250,000.

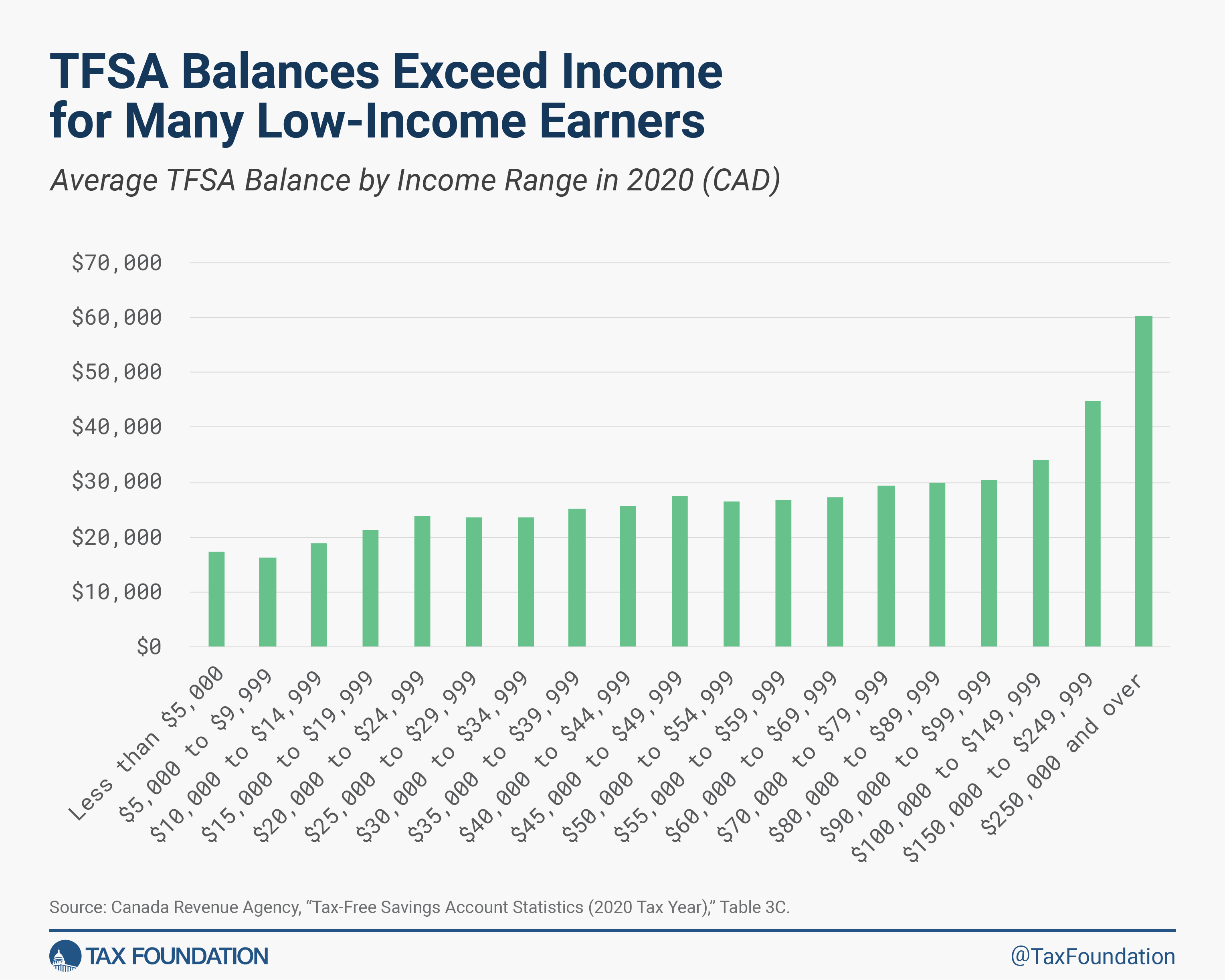

The average TFSA balance rises with income but is still quite substantial for all income groups, in fact exceeding income for many low-income earners. For the lowest income group—people earning less than CAD 5,000—the average TFSA balance is about CAD 17,000. For people earning between CAD 15,000 and CAD 20,000, the average TFSA balance is about CAD 21,000. TFSA balances rise to about CAD 60,000 on average for people earning more than CAD 250,000.

In short, Canada’s universal savings accounts appear to be a huge success in terms of encouraging private saving and financial security for households across the income scale, effectively establishing an accessible rainy-day fund for millions of low- and middle-income households. Low-income households in particular strongly prefer and utilize TFSAs rather than tax-advantaged retirement accounts.

Lawmakers in the U.S. should take note: sometimes simpler is better. Low- and middle-income households would benefit greatly from a simplified system of tax-advantaged saving, one that provides ready access to funds to cover emergencies and other short-term expenses without a tax penalty. Universal savings accounts have worked wonderfully in Canada, and there is no reason to think they wouldn’t work just as well in the U.S.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

Share