Supreme Court to hear challenge to Telecom Access Program on “nondelegation”.

CASE PREVIEW

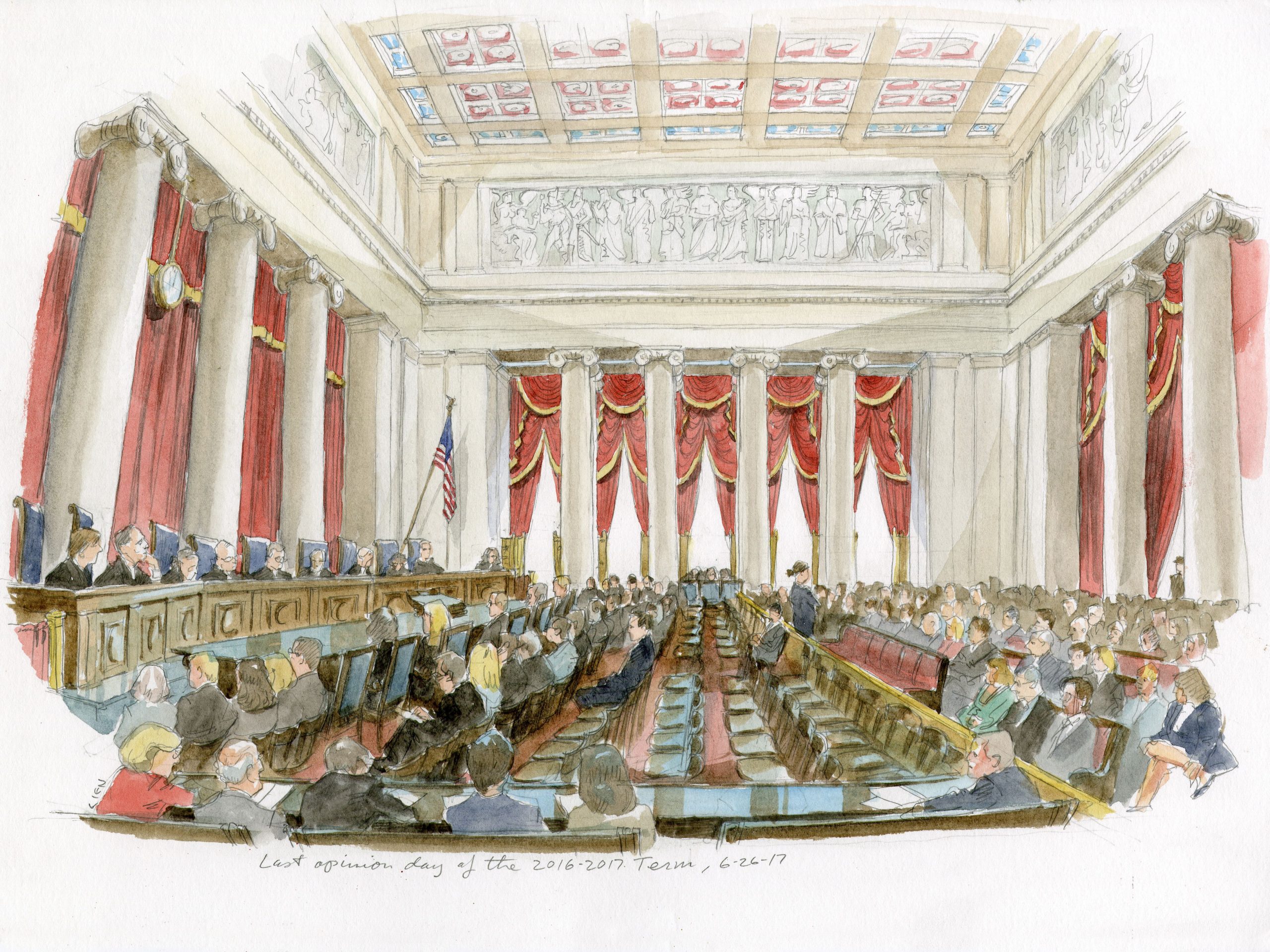

On Wednesday morning, the court will hear arguments regarding FCC v. Consumers’ Research. (Amy Lutz via Shutterstock)

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on Wednesday in a major challenge to the federal “E-rate program,” which subsidizes telephone and high-speed internet services in schools, libraries, rural areas, and low-income communities in urban areas. The stakes are high not only because the program is so large, but also because conservative lawyers and business organizations have been urging the court to revive the nondelegation theory, which is at the heart of the challengers case. If the justices accept this invitation, it could be a step in the recent efforts of the court to curtail the powers of federal agencies. The telephone industry was deregulated in 1996, and Congress created a new funding system for universal service that used more explicit subsidies. The Telecommunications Act of 96 created the Universal Service Fund, which was intended to facilitate universal service. This included telecommunications, information services, and rural health care providers. Telecommunications companies contribute to the fund which is then used to subsidise universal service. Under FCC regulations, carriers can and do pass the costs of the contributions, which are calculated every quarter, on to their customers.

Consumers’ Research describes itself as the country’s oldest consumer protection agency and has in recent years shifted its focus to fighting “woke” corporations, DEI initiatives, and the consideration of climate change on Wall Street. The group is funded in part by Leonard Leo, the Federalist Society co-chair who has raised hundreds of millions of dollars for conservative legal campaigns and helped pick or confirm each of the court’s six conservative justices.

Last year, the justices took a major step to weaken the power of administrative agencies when they overturned the Chevron doctrine, which significantly curtailed the power of agencies to interpret the laws they implement. The executive director of Consumers’ Research, Will Hild, was a co-founder of the firm that successfully brought one of those two cases.

Consumers’ Research filed challenges to the Universal Service Fund contributions calculated for several different quarters in the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the 5th, 6th, 11th, and District of Columbia Circuits.

Three-judge panels in the 6th and 11th Circuits rejected the group’s challenges in those circuits, and the 6th Circuit denied the group’s petition for rehearing. The D.C. Circuit dismissed the group’s challenge there.

Consumers’ Research was also initially unsuccessful in the conservative 5th Circuit, where a three-judge panel unanimously rejected its challenge. But the full court of appeals agreed to rehear the case and reversed, by a vote of 9-7.

In a decision by Judge Andrew Oldham, who is often mentioned as a potential nominee for the Supreme Court if a vacancy occurs during the Trump administration, the majority deemed the contributions to the fund a “misbegotten tax” that violates the provision of the Constitution giving Congress sole power to legislate.

Oldham reasoned that Congress may have violated the nondelegation doctrine by giving the FCC the power to set the amount that telecommunication carriers must pay into the fund without giving it an “intelligible principle” – as the nondelegation doctrine currently requires – to guide it. Oldham explained that the FCC could have violated the doctrine of nondelegation by giving the power to set fees to USAC. But at the very least, Oldham concluded, “the combination of Congress’s sweeping delegation to FCC and FCC’s unauthorized subdelegation to” the USAC violates the Constitution.

The FCC (along with a group of trade associations representing entities that receive funding through the E-rate program and a trade association for the telecommunications industry) went to the Supreme Court, which agreed in November to review the 5th Circuit’s decision.

In its brief in the Supreme Court, the FCC insists that Congress did not improperly delegate legislative power to it. Under the current nondelegation doctrine, it stresses, Congress can give a federal agency discretion to implement a statute as long as the law meets a standard that is “not demanding” – “it supplies an intelligible principle to guide the agency — that is, if it defines the general policy that the agency must pursue and the boundaries of the agency’s power.”

For more than a century, the FCC contends, the Supreme Court has rejected challenges to laws that give federal agencies broad discretion, including laws directing agencies to regulate “in the public interest,” set “just and reasonable” rates for natural gas, recover “excessive profits” from military contractors, and set “fair and equitable” prices for commodities.

Congress did the same thing here, the FCC says. The law creating the Universal Service Fund outlines a general policy that Congress wants the agency to follow. For example, it aims to ensure that internet and phone services are affordable and that rural areas have access to these services. It also aims to provide “reasonably similar” services and to ensure that schools and libraries can use them. The law also defines the FCC’s powers: It provides “detailed guidelines” about “who is required to pay universal service contributions, how they are to be paid, what the funds can be used for, and which entities may receive funding.”

The Schools, Health and Libraries Coalition, who is also defending E-rate, says that federal courts enforced limits even before the Supreme Court decision in 2024, Loper-Bright Enterprises V. Raimondo, which held that courts cannot defer The coalition notes that federal courts will now be more skeptical of FCC actions, since the FCC interpretations no longer receive any deference. The coalition claims that Congress has defined the “controlling policies” which are the basis of the law. The FCC maintains that it has not improperly delegated power to USAC. The FCC argues that a federal agency can “properly solicit and rely upon private advice” when exercising executive power. Here, the FCC writes, it decides how much money the carriers must contribute to Universal Service Fund. USAC only provides nonbinding advice on, for example, projected expenses for universal service programs and revenues that the carriers are expecting. The FCC notes that it can always change projections before calculating the contribution carriers must pay. The FCC argues that if taken to its logical conclusion, the court’s approach could allow litigants to claim that members of Congress delegated legislative powers by relying on too many staffers, that the President delegated executive authority by relying on too many advisers, or that judges delegated judicial powers by relying on too many law clerks. The coalition argues that the E-rate laws charge the FCC with carrying out Congress’s instructions; USAC has a “ministerial role.” Both the FCC as well as the coalition reject the 5th Circuit’s conclusion that a combination of Congress’s grant of discretion to the FCC along with the FCC’s reliance on USAC’s advice violates the doctrine of nondelegation. The coalition argues that this determination is inconsistent with Supreme Court cases which have separately considered public and private nondelegation. Alaska explains that with 80% of its state being inaccessible via roads or highways wireless and internet services are “critical” for health care, 911 emergency systems, education, as well as everyday life. The Fund’s existence is not about subsidizing telecommunications, but whether rural Alaskans will have reliable access to telecommunications at all. The groups claim that Congress would have to “restructure the FCC” in order to use the remaining funds. This could take many years. Moreover, the groups note, the E-rate program facilitates the enforcement of the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which Congress passed in 2000 to “address concerns about children’s access to obscene or harmful content over the Internet,” because the law makes discounts from the E-rate program contingent on compliance with the CIPA’s requirements.

Consumers’ Research counters that the fund’s “revenue-raising mechanism is a historic anomaly at odds with 600 years of Anglo-American practice.” If the E-rate program is upheld, the group suggests, and Congress were able to pass similar laws in other contexts, “there would be no need to pass budgets or make appropriations ever again. Consumers’ Research argues that the law creating the E rate program unconstitutionally delegated power to the FCC. Consumers’ Research cites Judge Kevin Newsom from the 11th Circuit to argue that “the FCC almost certainly exercises legislative power when it determines… the size of the universal-service programme.” Furthermore, the group adds that the universal-service is “at least equally bad” as the laws that the Supreme Court struck under the nondelegation theory in 1935, which was the last time that doctrine was invoked. This power is so important that Congress must approve both the efforts to raise revenue and the amount to be raised. Instead, the group says, Congress outsourced to the FCC its power to tax without the kind of specific limits on the size of the tax that have “been a near-universal aspect of Anglo-American constitutional law for centuries.”

Congress’s grant of power to the FCC also runs afoul of the current version of the nondelegation doctrine, the group writes, “which still requires Congress to ‘clearly delineate’ delegated power.” The law at issue here fails to provide any such clear instructions, the group maintains. Instead, the FCC is guided only by “universal principles” that are not mandatory but merely “aspirational.” Moreover, Congress has even allowed the FCC to add new “principles” or “even redefin

‘universal service’ altogether.”

But in any event, the delegation to the FCC still violates the nondelegation doctrine because the “FCC is guided by its own ‘aspirations,’ and for good measure Congress let the agency expand its own scope of authority at will by adding new universal service principles and even redefining ‘universal service’ altogether.”

The FCC has violated the private nondelegation doctrine, Consumers’ Research asserts, because it has “largely handed off” the power to raise money to the USAC. Consumers’ Research claims that once the USAC has proposed the contributions carriers should make to this fund, the FCC doesn’t do any independent or substantive review of these projections. Instead, they are simply “‘deemed approved” fourteen days later.”

Consumers’ Research and its supporters push back against suggestions that allowing the 5th Circuit’s ruling to stand will have negative repercussions around the country. Consumers’ Research, along with 14 other states and the Arizona legislature, tells the justices in a supporting brief that state courts have struck down statutes “without catastrophic effects” when they apply “a strong conception of nondelegation grounds.”

A supporting brief filed by West Virginia (along with 14 other states and the Arizona legislature) similarly tells the justices that state courts applying “a strong conception of nondelegation grounds” have struck down statutes “without catastrophic effects.”

When it granted review, the Supreme Court asked the litigants in the case to address whether the case is moot – that is, no longer a live controversy – because the challengers did not ask the court of appeals for preliminary emergency relief.

The FCC and all of the groups involved in the case agree that the dispute is not moot. The dispute is over the amount of contribution made by the carriers in the first quarter 2022. Because that quarter is over, the FCC contends, the challengers can no longer obtain future relief, and they may not be able to get a refund because the government is immune from claims for monetary relief.

However, because there is a new contribution set each quarter, and three months is not enough time to litigate a challenge to that contribution, the FCC continues, the dispute falls into an exception for cases that might otherwise be moot but are “capable of repetition, yet evading review.”

This is true, the FCC says, even when Consumers’ Research did not ask the court of appeals to put the contribution for the specific quarter it is challenging on hold. The FCC argues that if this case is dismissed, it will encourage challengers to seek preliminary relief for future cases. The Schools, Health, and Libraries Coalition also agrees that this case is not moot. But if the Supreme Court ultimately concludes that it is, the coalition tells the justices, it should invalidate the 5th Circuit’s ruling, because the case would already have been moot before that court issued its decision.

Consumers’ Research also insists that the case is not moot, writing that carriers can still seek the return of the money that they paid to the fund during the quarter in which they challenged the scheme – which is not prohibited by sovereign immunity because they are seeking restitution, not money damages.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.