Supreme Court, once again, rejects California treatment of arbitration

OPINION ANALYSIS

on Jun 16, 2022

at 12:09 pm

The holding of Wednesday’s decision in Viking River Cruises v. Moriana will surprise nobody. As it has so many times before, the Supreme Court rejected California’s treatment of arbitration under California law, in this case California’s Private Attorneys General Act. The most surprising thing about the decision is how close it came to unanimity. Eight of the nine justices agreed in the result, with the lone dissent coming from Justice Clarence Thomas, who long has held that the relevant federal statute (the Federal Arbitration Act) does not apply to cases in state courts.

The Private Attorneys General Act, PAGA, permits any individual employee to sue her employer and assert claims against the employer on behalf of all employees for any of the employer’s violations of any provision of California’s (lengthy) Labor Code. California employers (like Viking River Cruises) routinely obtain pre-dispute arbitration agreements from their employees; those agreements routinely (and in this case) include an explicit waiver of the employee’s right to pursue those aggregate claims under PAGA. The California state courts (predictably) rejected that waiver as inconsistent with PAGA. Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion, in turn, rejected that holding, validating the ability of the employer to hold the employee to bilateral arbitration limited to the employee’s own claims.

Alito starts by repeating the court’s long-standing view that Congress adopted the FAA “in response to judicial hostility to arbitration.” He discusses two lines of cases under the FAA. First, quoting earlier decisions, he summarizes “an equal-treatment principle … [that] preempts any state rule discriminating on its face against arbitration.” That equal-treatment principle has included most of the court’s cases under the FAA, several of which have reversed decisions of the California Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit (the federal appellate court that covers California).

More recently, the court has begun to add substantive content to the FAA, reversing decisions that apply even-handed rules if, in the terms of one earlier case Alito discusses, they “could be used to transform ‘traditional individualized arbitration’ into the ‘litigation it was meant to displace’ through the imposition of procedures at odds with arbitration’s informal nature” (cleaned up). Alito explains that this second principle has led the court to hold, in the terms of one prior case, that “a party may not be compelled under the FAA to submit to class arbitration unless there is a contractual basis for concluding that the party agreed to do so.”

Ultimately, Alito finds “a conflict between PAGA’s procedural structure and the FAA,” because the PAGA “permits ‘aggrieved employees’ to use the Labor Code violations they personally suffered as a basis to join to the action any claims that could have been raised by the State in an enforcement proceeding.” Thus, for Alito, PAGA “unduly circumscribes the freedom of parties to determine ‘the issues subject to arbitration’ and ‘the rules by which they will arbitrate,’” something the court will not tolerate. Hence, the employee is free to arbitrate her claim against the employer, but she cannot raise the PAGA claim on behalf of other employees in that arbitration. Because the employee cannot raise the individual claim in a judicial proceeding, the employee is left unable to raise the representative part of the PAGA claim in any forum at all.

Before the straightforward condemnation of PAGA quoted in the preceding paragraph (Part III of Alito’s opinion), Alito oddly includes a discursus of several pages that seems strangely remote from PAGA. The general point of that section is that PAGA is best viewed as a “representative standing” statute – with the aggrieved employee pursuing claims as a representative of California’s labor agency – and that the FAA need not mandate the enforcement of all “waivers of standing to assert claims on behalf of absent principals.” The discussion mentions such far-flung examples as “shareholder-derivative suits, wrongful-death actions, trustee actions, and suits on behalf of infants.” I discuss this passage – plainly unnecessary to the decision – because it sparked considerable disagreement among the justices.

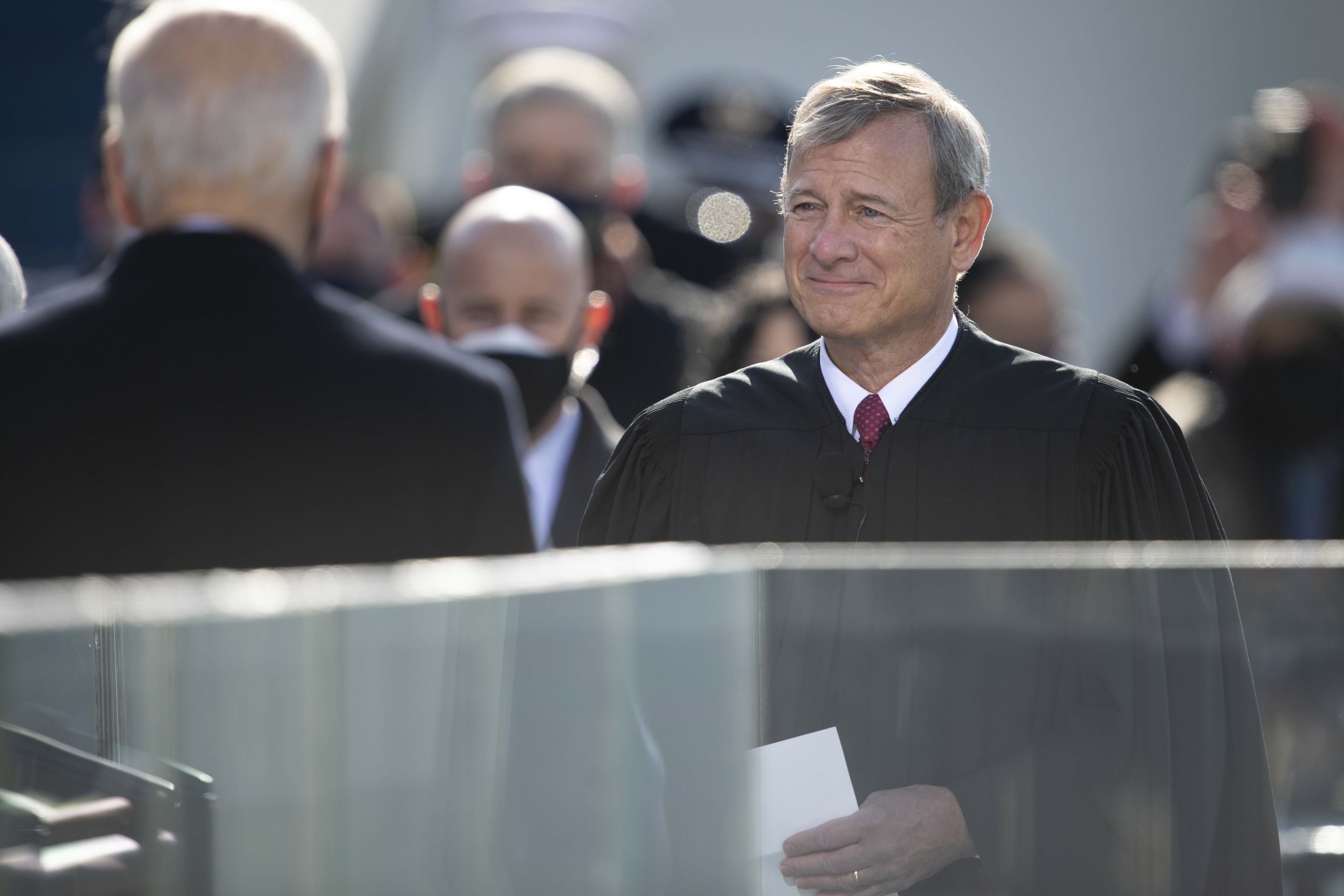

To explain, Justice Sonia Sotomayor (who often dissents in FAA cases), concurred in all of Alito’s opinion, explaining in a separate opinion that she approved especially of the discussion in Part II of all the things that Alito said the FAA did not preempt. Conversely, three of the justices who typically are in the majority in FAA cases supporting arbitration (Justice Amy Coney Barrett, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh), wrote separately to distance themselves from Part II of the opinion, limiting their agreement to the brief analytical discussion in Part III. Perhaps this apparently pointless bickering is evidence of a slight fray of tempers at the court this June.

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to SCOTUSblog in various capacities, was counsel on an amicus brief in support of Viking River Cruises in this case. The author of this article is not affiliated with the firm.]