Stock Buyback Excise Taxes: What We Know And Don’t Know

Companies now spend more than a $1 trillion annually to repurchase their stock, in lieu of paying higher dividends to their shareholders, or investing more in their workers, factories, or equipment. Last year, Congress required publicly-traded companies to pay a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks, which continued apace.

President Biden now has proposed to increase the buyback tax to 4 percent, which Democratic congressional leaders quickly endorsed. A 4 percent buyback tax would further reduce the tax advantages of buybacks over dividends. Less clear are impacts on small investors and workers.

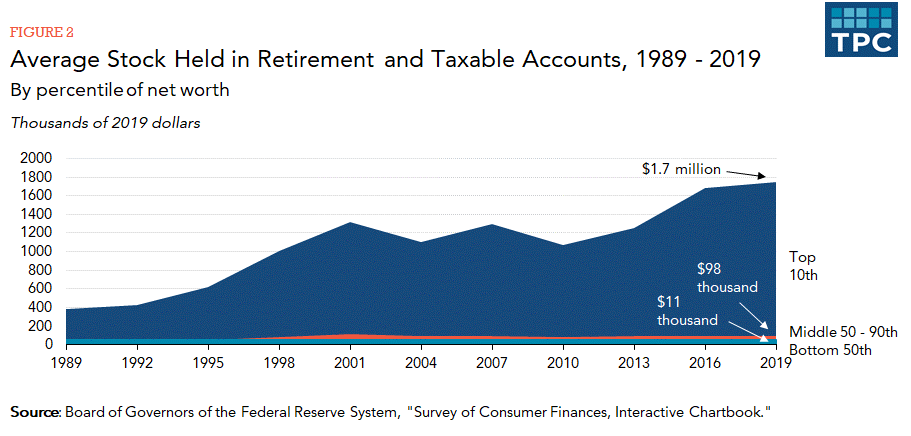

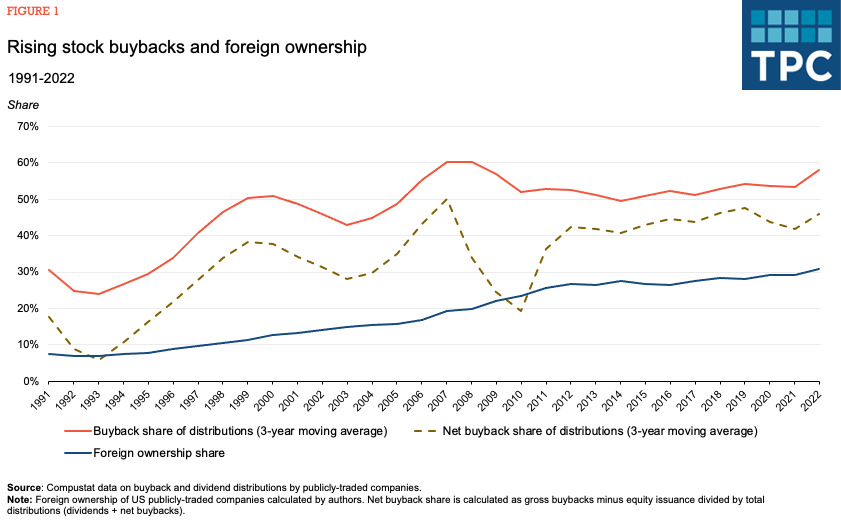

First, it is clear that corporate buybacks and foreign ownership rose sharply over the past three decades.

Buybacks and dividend distributions are largely interchangeable, apart from tax considerations. But, over the last three decades, the share of buybacks doubled, from 30 to 60 percent of all distributions. Buybacks net of stock issuances similarly rose (some companies buy back their stock to issue to their employees).

The share of foreign investors of US publicly traded stock also tripled. This increased presence of foreign investors, and the tax benefit they enjoy, adds fuel for buybacks.

Second, US tax rules still favor buybacks over dividends even with the new 1 percent excise tax.

Today, foreign investors, and US taxable shareholders, each account for about 30 percent of publicly traded stock, while US tax-exempt shareholders account for the remaining 40 percent.

Foreign investors strongly prefer buybacks to dividends from a US tax perspective. They pay no US tax on their capital gains, but the dividends they receive are subject to a 30 percent tax (often reduced to 15 percent for those that reside in a country that has a tax treaty with the US). Foreign investors may pay taxes on capital gains or dividends in their home country, but typically, there, they also pay lower taxes for capital gains than dividends (and, often, pay no tax on capital gains).

There also is some, albeit smaller, US tax advantage for buybacks over dividends for US taxable shareholders. Those who choose not to sell their shares, like Warren Buffett, may defer taxes on their unrealized gains—and potentially avoid them completely by holding their shares until death. By contrast, they pay tax on dividends at a top rate of 23.8 percent.

But most US shareholders, like 401(k), IRA, and other retirement plans are tax exempt, and therefore indifferent on buybacks versus dividends.

We used these three broad categories (foreign investors, US taxable shareholders, and US tax exempt shareholders), to estimate the US tax collected, on average, from an extra dollar of buyback versus a dollar of dividend. We estimated, on average, the US tax differential between buybacks and dividends is between 5 and 8 percent.

Foreign shareholders account for about 5 percent of the differential, which is the difference between “0” and the share of foreign shareholders (30 percent) times 16.8 percent, the average effective rate on dividends paid to foreign shareholders for 2017, the most recent year available. US taxable shareholders account for between 0 and 3 percent of the tax differential, depending on the assumptions, which are hard to pin down. And, of course, US tax exempt shareholders pay no tax on either buybacks or dividends.

With a tax differential between 5 and 8 percent between buybacks and dividends, there’s room to increase the buyback tax from 1 percent to 4, and still leave buybacks with a tax advantage over dividends.

Now to the effect on small investors and workers.

Some assert that increasing stock buyback taxes “would hit the little guy,” because households across the income spectrum own stock through 401(k) and other retirement accounts.

But, as noted above, foreign investors own 30 percent of US publicly traded stock. And, for the stock held by US taxpayers, the buyback tax would hit few “little guys.” In 2019, the most recent year available, the richest tenth of US households owned an average of $1.7 million of stock while those in the bottom 50 percent owned an average of only about $11,000. Virtually all (94 percent) of the wealthiest 10 percent of households owned stocks, while only about a third (31 percent) of the bottom 50 percent owned stock, either directly or through, for example, mutual funds or 401(k)s. “Little guys” own little stock.

Others argue extra taxes on buybacks or dividends encourage companies to invest more in “worker training, research, modernizing equipment and other [investment] activities.” Again, however, the evidence is more complicated. That is because companies generally distribute earnings to their shareholders, either in the form of buybacks or dividends, when they cannot find attractive investments. The “new view” of finance theory also suggests that additional taxes on distributions do not lead companies to retain more capital, although empirical evidence on this point is mixed.

In our view, a higher tax on buybacks would mainly lead to more dividends, which doesn’t benefit workers. But that’s OK, because the US could collect more taxes, which are sorely needed, largely from foreign investors.