Something’s Screwy with Immigration Court Border Cases

The immigration courts are a component of the Department of Justice (DOJ), and a review of DOJ statistics on decision filing rates in border asylum cases reveals that something screwy is going on — asylum grants are down, but so are asylum denials, while the percentage of “other” determinations are way up. What gives?

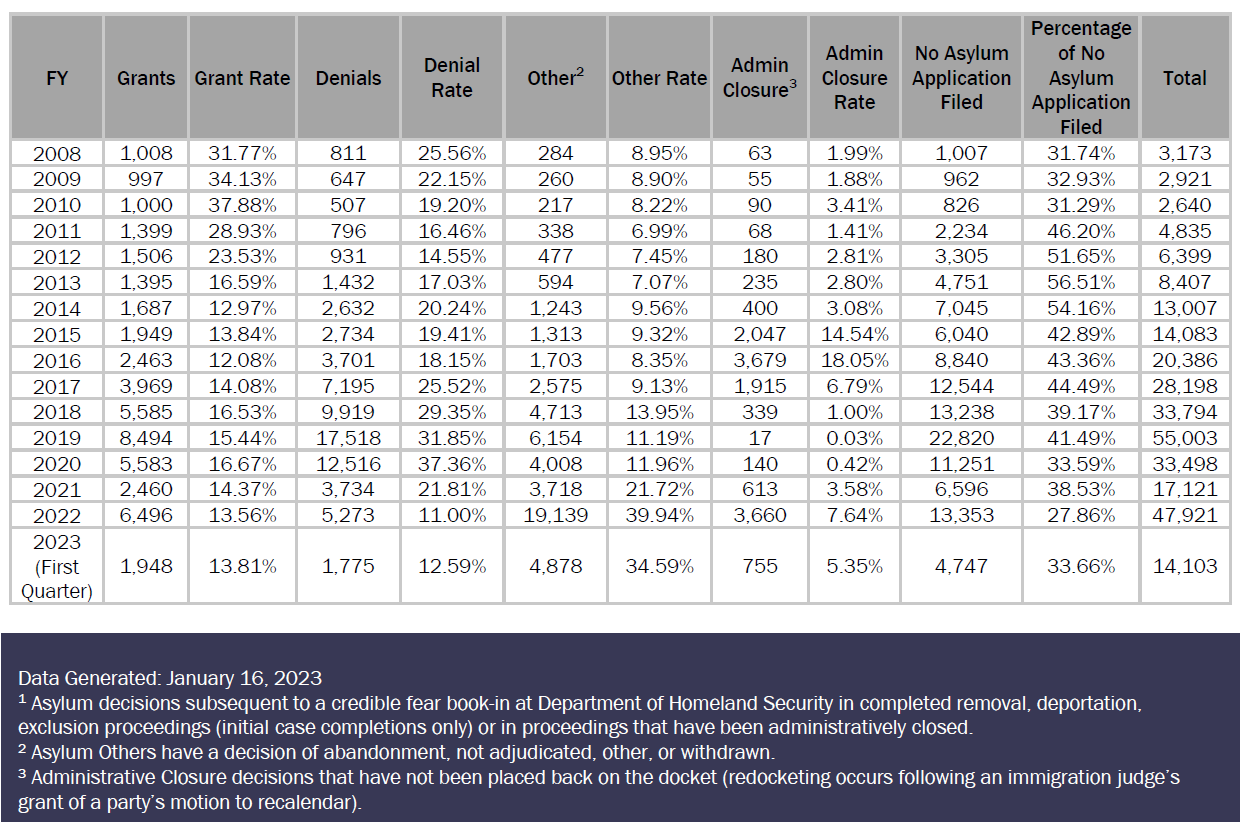

“Asylum Decision and Filing Rates in Cases Originating with a Credible Fear Claim”. The statistics, issued by DOJ’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) — the agency that oversees the immigration courts and the appellate Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) — are formally captioned “Asylum Decision and Filing Rates in Cases Originating with a Credible Fear Claim” (see a screenshot from the pdf file at the end of this post, from item 10 here). The title requires some brief explanation.

Both Border Patrol apprehensions of illegal entrants and aliens deemed inadmissible by CBP officers at the ports of entry are referred to as “encounters”, and when CBP encounters either an illegal entrant or an alien who has presented fraudulent admission documents or no admission documents at all, it has a choice.

The president’s policies have encouraged so many aliens to enter illegally that the executive branch is dispensing with the rules to keep the train on the tracks and hide the disaster.

The agency can either place the encountered alien into “regular” removal proceedings under section 240 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) before an immigration judge (IJ), or it can process the alien under “expedited removal” pursuant to section 235(b)(1) of the INA.

Expedited removal allows CBP to remove such encountered aliens directly, without obtaining a removal order from an IJ, but it comes with a catch. If an alien subject to expedited removal claims a fear of harm if returned or requests asylum, CBP must refer the alien to a USCIS asylum officer (AO) for a “credible fear” interview.

Credible fear is a screening process used to determine whether an alien may be eligible for asylum, and therefore the credible fear standard is lower than the burden an alien must carry to be granted asylum. Specifically, credible fear is defined by statute as “a significant possibility … that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum” (emphasis added).

Aliens who receive a “positive credible fear determination” from an AO are almost always referred to regular section 240 removal proceedings before an IJ to apply for asylum. Consequently, to figure out whether illegal migrants who request asylum once they are encountered by CBP have good claims, bad claims, or no claims at all, these statistics are the best place to start.

Three Caveats. Before I proceed further, however, I have three caveats.

The first is that DHS under the Biden administration has grievously underutilized the expedited removal tool that Congress gave it. For example, of the nearly 785,000 illegal migrants apprehended by Border Patrol agents at the Southwest border in the first seven months of FY 2023 who weren’t expelled under Title 42, fewer than 71,500 of them — 9.7 percent of the total — were subject to expedited removal.

In lieu of expedited removal, the Biden administration has chosen to simply release most of the illegal migrants Border Patrol has apprehended at the U.S. Mexico line. It has either shuffled them out the door directly into section 240 removal proceedings (the choice in more than 166,000 cases this fiscal year, or 22.7 percent of all apprehended aliens not expelled), or on parole (nearly 295,000 cases thus far in FY 2023, or 40 percent of apprehended migrants who weren’t expelled).

The latter category, the aliens released on parole, lead me to my second caveat. Those aliens aren’t going to be in removal proceedings for a while, and by “a while” I mean for up to a decade or more. In fact, in February NBC News reported that there were nearly 600,000 border aliens released on parole who hadn’t been served with the papers that would even get them in to see an IJ.

Instead, they’re allowed to live and work here indefinitely, building up the “equities” (jobs, houses, families, kids) that will make it impossible to remove them ever, all the while — as my colleague George Fishman has explained — gaining time that will quickly make them eligible for federal benefits.

In any event, most of those paroled aliens won’t show up in any DOJ statistics anytime soon. Assuming that I am still working (or alive) in 10 years, catch me then and I will tell you how their cases are going.

That said, as I have explained elsewhere, regardless of whether those migrants are being cut loose and sent directly to removal proceedings or alternatively being released on parole so they can wait around for years to be placed into removal proceedings, the Biden administration has no authority — at all — to just release them en masse as it has been doing.

I know that, and for what it’s worth, the administration knows that (despite its claims to the contrary), but neither the president nor his DHS secretary, Alejandro Mayorkas, cares.

What they will say is that so many aliens are coming to the border illegally that they can neither detain those aliens nor subject them to expedited removal — now. To borrow an analogy from my colleague Mark Krikorian they are like “Lucy in the chocolate factory”, moving aliens out as quickly as possible in the hope that things will be better tomorrow, and they can finally do what’s right.

But for Joe Biden’s border, tomorrow never comes; all of those releases simply encourage even more migrants to arrive, as a federal judge recently held.

The third caveat is that many if not most of the aliens who have received asylum decisions from IJs of late after making credible fear claims were apprehended under the Trump administration. Still, the DOJ statistics give you some idea of the strength of border asylum claims, and what IJs are doing with them.

Back to the DOJ Chart. Which brings me back to the DOJ asylum decision rate chart.

In the first quarter of FY 2023, IJs completed 14,103 cases involving aliens (most if not all encountered at the Southwest border) who were placed into removal proceedings to apply for asylum after receiving positive credible fear determinations.

In 1,948 of those cases, or less than 14 percent of the total, asylum claims were granted. In other words, only one in every 7.24 migrants stopped at the border had a good asylum claim. The administration, however, still acts as if they all have good claims, until an IJ finds otherwise.

In 1,775 of those cases, or 12.59 percent of the total, asylum was denied. That means that 73.6 percent of the cases — 10,380 in total — were completed by an IJ who neither granted nor denied an alien asylum.

To be clear, not every asylum case that originates with a credible fear claim ends up with either an asylum grant or denial. In certain instances, the claim is shelved indefinitely for the court’s convenience, a scheme called “administrative closure”.

In the first quarter of FY 2023, 755 cases (5.35 percent of the total) that originated with a credible fear claim were, in fact, administratively closed. That still leaves 9,625 cases that were completed but not granted, denied, or closed, more than 68 percent of the total. That’s where the “screwy” comes in.

Historical Comparisons. I’ll give you some educated guesses about what happened in those cases, but first I want to compare the latest figures with prior years. In FY 2019, the last year before the Covid-19 pandemic, IJs completed just over 55,000 such cases, granting nearly 8,500 (15.44 percent), denying more than 12,500 (37.36 percent), and administratively closing 17 (.03 percent) — more than 26,000 cases in total, or 47.3 percent.

In FY 2018, a year in which IJs completed nearly 34,000 cases that started with a credible fear claim, they granted asylum to 5,585 aliens (16.53 percent), denied asylum claims in more than 9,900 others (29.35 percent), and administratively closed 17 (1 percent) — accounting for 47 percent of all decisions.

There’s a big difference between roughly 47 percent of all cases being completed with a grant, denial, or closure, and 32 percent of them being completed in one of those three manners. So, what gives?

What Gives. The most significant other option that I have not discussed is that many of those aliens whose cases originated with a credible fear claim failed to appear in court, and IJs completed their cases by ordering them removed in absentia or instead by simply dismissing their cases in the hopes they show up later.

Congress requires IJs to issue in absentia orders to alien respondents who fail to appear, so long as ICE proves that they received notice of the hearing. And yet, anecdotally I have heard ICE attorneys are not pushing for such orders in certain cases, for whatever reason.

While there has been a great deal of debate between immigration hardliners and aliens’ advocates over the in absentia rate (most of it tendentious), EOIR’s own statistics reveal that of the 91,000-plus overall IJ decisions (including border claims and all other removal cases) in the first quarter of FY 2023, a third — 33 percent — were in absentia removal orders.

The “no-show” rate for cases that originated with a credible fear claim is likely at least that high. The EOIR “Asylum Decision and Filing Rates in Cases Originating with a Credible Fear Claim” chart reveals that 4,878 IJ decisions — nearly 34.6 percent of the total — in the first quarter of FY 2023 were closed under the category “Other”.

“Other” cases are defined therein as “a decision of abandonment, not adjudicated, other, or withdrawn”. In absentia removal orders would fall under the first three categories.

That said, in absentia orders could also fall under two other categories: “denials” and the one I haven’t mentioned yet, “no asylum application filed”. More than a third (33.66 percent) of the decisions in cases that originated with credible fear claims involved aliens who never filed an asylum application — which is remarkable when you consider that the only reason they were sent to court was to apply for asylum.

In any event, a no-show would be a denial if the alien respondent failed to appear after filing an asylum application, while it would fall under the no asylum application filed category if the respondent either never appeared at all (and thus never filed an application) or no-showed after appearing but before filing an application.

It would be helpful if EOIR revealed how many cases involving border migrants placed into proceedings after making a credible fear claim resulted in absentia orders — which, as the other EOIR statistics I cited show, they could do. EOIR simply doesn’t.

There’s still something screwy, however. In the five fiscal years between FY 2015 and FY 2019, just 10.4 percent of all cases originating with a credible fear claim, on average, were completed under that “other” category. The “other” rate in the first quarter of FY 2023 was more than three times higher, and higher still in FY 2022 (nearly 40 percent) — both years under the Biden administration.

That suggests that Biden’s DOJ — and perhaps also ICE — is handling those cases differently than they have in the past.

What I do know is that a memo issued by ICE’s “principal legal advisor” (the agency’s de facto general counsel) in April 2022 directed her attorneys to drop cases that should have resulted in removal orders, and in April I explained that ICE’s FY 2024 budget documents revealed that the agency’s lawyers had in fact tanked nearly 92,000 cases that logically would have resulted in removal orders in FY 2022.

Why is Biden’s ICE doing that? They’ll claim it’s in the interests of justice and equity, but it’s really being done for the same reason Biden’s CBP has released more than two million illegal migrants it was supposed to detain: The president’s policies have encouraged so many aliens to enter illegally that the executive branch is dispensing with the rules to keep the train on the tracks and hide the disaster.

Key Takeaways. Statistics are just statistics, and the pundit must explain what they mean. DOJ hasn’t given this pundit much to go on, but here are a few key takeaways: Few migrants who enter illegally have valid asylum claims; a third or more probably aren’t showing up in court; a third aren’t even applying for asylum; and the administration likely isn’t even trying to get removal orders in those cases, let alone remove them.

That’s all screwy.