Sneaker Parodist Gets Schooled: MSCHF Can’t Sidestep Trademark Infringement by Claiming Artistic Expression | Irwin IP LLP

Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Prod. Studio, Inc. (Dec. 5., 2023)

The Second Circuit was the first Circuit Court to address Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, where the Supreme Court explained that when an alleged trademark infringer relies upon the goodwill of a trademark owner to market its own goods, the standard likelihood of confusion test applies even if the mark is used for an expressive purpose. In a per curium opinion, the Second Circuit held that no special First Amendment protections applied to protect MSCHF Production Studio (“MSCHF”) against trademark infringement claims by Vans, Inc. Instead, the likelihood of confusion test was appropriate despite a claim that the limited-edition sneaker was protected parody.

The Second Circuit first laid out the two legal tests. In assessing trademark infringement, courts generally use a multi-factored likelihood of confusion test. In the Second Circuit, courts use the “Polaroid” factors: (1) strength of the mark, (2) similarity of the marks, (3) proximity of the marks in the market, (4) likelihood the prior owner may “bridge the gap”, (5) actual confusion, (6) defendant’s good faith, or lack thereof, (7) product quality, and (8) consumer sophistication. However, when an accused product is a parody, courts have instead applied the so-called Rogers test. The Rogers test raises the bar for infringement, requiring the plaintiff to show the use of the trademark is not artistically relevant to the work or is explicitly misleading consumers as to the source for expressive works. Last June, the Supreme Court in Jack Daniels clarified that even if the accused infringer claims parody, the Rogers test does not apply if the alleged infringer uses the plaintiff’s mark for source identification, i.e. as a trademark.

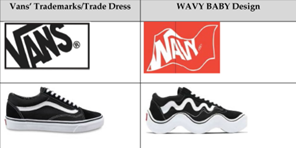

The Court then considered whether the use of trademarks and trade dress similar to Van’s should be evaluated under the Polaroid or Rogers test. Although distorted, MSCHF incorporated the Van’s black and white color scheme, the side stripe, the perforated sole, the logo on the heel, the logo on the footbed, and the packaging. Further, MSCHF did so without a disclaimer to disassociate the product from the plaintiff. These features, in addition to defendant’s admission that it started with the plaintiff’s mark in its design process, evidenced use in a source-identifying manner. After this determination, the Second Circuit applied the Polaroid test. Especially compelling was evidence of intent, actual confusion, and a similarity in terms of marketing: both MSCHF in this case and Van’s historically had partnered with artists to introduce limited edition shoes through similar channels of trade. The Court found the District Court’s conclusion to be correct and a preliminary injunction warranted.

Despite additional protections available under the Rogers test, the Second Circuit, who originally decided Rogers, made clear that companies should not expect an extra shield or to sidestep the likelihood of confusion factors by simply dubbing their goods a parody.