Should Congress Extend Bonus Depreciation?

Although Congress managed to reach a year-end topline spending agreement, it left many tax questions unanswered heading into 2023. One is considering whether to allow firms to continue to take an immediate tax deduction for their investments in equipment and some structures.

Bonus depreciation would spur some new investment and economic growth. However, the Tax Policy Center estimates continuing the special deduction would reduce federal revenues by $250 billion over the next decade, benefit some corporations more than others, and subsidize a portion of investment that would happen anyway.

Bonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a fraction of their investment spending right away, with the rest deducted in future years. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) increased bonus depreciation from 50 percent to 100 percent through this year. But beginning in 2023, bonus depreciation is schedule to decline by 20 percentage points each year until 2027, when it is no longer available.

TPC estimates that in 2020, about 80 percent of business investment in equipment and structures was eligible for bonus depreciation. The idea isn’t new: Congress has treated investment in equipment favorably since the 1940s, either with accelerated depreciation or with investment tax credits.

Rapid depreciation can spur investment by lowering the effective tax rate on the return from new assets. Think of it as an interest-free loan from the government. Firms avoid tax today but lose benefits of depreciation in future years. In a period of relatively high interest rates, such as we are in now, bonus depreciation is even more valuable.

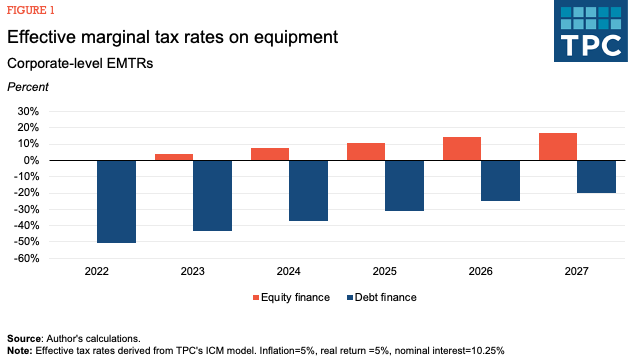

To measure how phasing out expensing would change the tax burden of new investment, TPC’s Investment and Capital Model calculated the effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) on new assets eligible for bonus depreciation. EMTRs measure the “tax wedge” between the pre-tax and after-tax returns for an investment that just breaks even after taxes, as a percentage of the pre-tax return.

In 2022, with full expensing, an inflation rate of 5 percent, and a real rate of return of 5 percent, the corporate-level EMTR is 0 percent. In other words, the investment is tax free. By 2027, the tax rate rises to around 17 percent.

Since companies also can deduct at least some interest expenses, their EMTRs on debt-financed capital investment can be negative. In 2022, the effective tax rate on such investments is a negative 51 percent. By 2027, their tax rate still would be negative, but only a negative 20 percent.

A study by Eric Zwick and James Mahon finds that between 2008 and 2010, expensing increased eligible investment by $73.6 billion to $125 billion annually. Proponents often argue that increased investment has positive effects on employment, especially in an economic downturn. The idea: Firms with more capital also hire more workers. A recent study by Mark Curtis and colleagues finds bonus depreciation led to higher employment but not higher wages in the early 2000s.

It is likely investment will decline if the TCJA’s expanded bonus depreciation phases out, though it is hard to know by how much. It’s also unclear which firms would benefit from extending it or whether continued expensing would spur investment as it did as the US was coming out of the Great Recession. There is little evidence on the impact of bonus depreciation since 2012.

One key question: Does bonus depreciation increase or merely accelerate investment? It originally was designed to be temporary, and firms may have responded by purchasing some of their investments sooner than they originally planned. If firms’ responses are mostly a timing shift, any increases in long-run growth would be much lower.

And while bonus depreciation increases overall investment, it also benefits investments firms would have made regardless. And some of this windfall has led to higher executive compensation at profitable firms.

Large firms invest a lot and some suggest they would be the primary beneficiaries of extending bonus depreciation. But Congress seems deeply conflicted about this potential windfall. Its concerns about large corporations not paying enough taxes led to passage this year of the new book minimum tax on large companies. Yet Congress excluded depreciation from the minimum tax, worried it would discourage investment.

Not all firms take advantage of bonus depreciation. TPC and Treasury research finds that already profitable firms are the most likely users. This could reduce competition by putting new or currently unprofitable firms at a disadvantage.

Before 2017, even firms with positive income on average used bonus depreciation for only 80 percent of new eligible investments. Among firms in a loss position the take-up rate was only 40-50 percent.

No doubt, extending bonus depreciation will boost investment by some companies. But how much it will benefit the overall economy is less clear.