Repealing Inflation Reduction Act Green Energy Tax Credits: Analysis

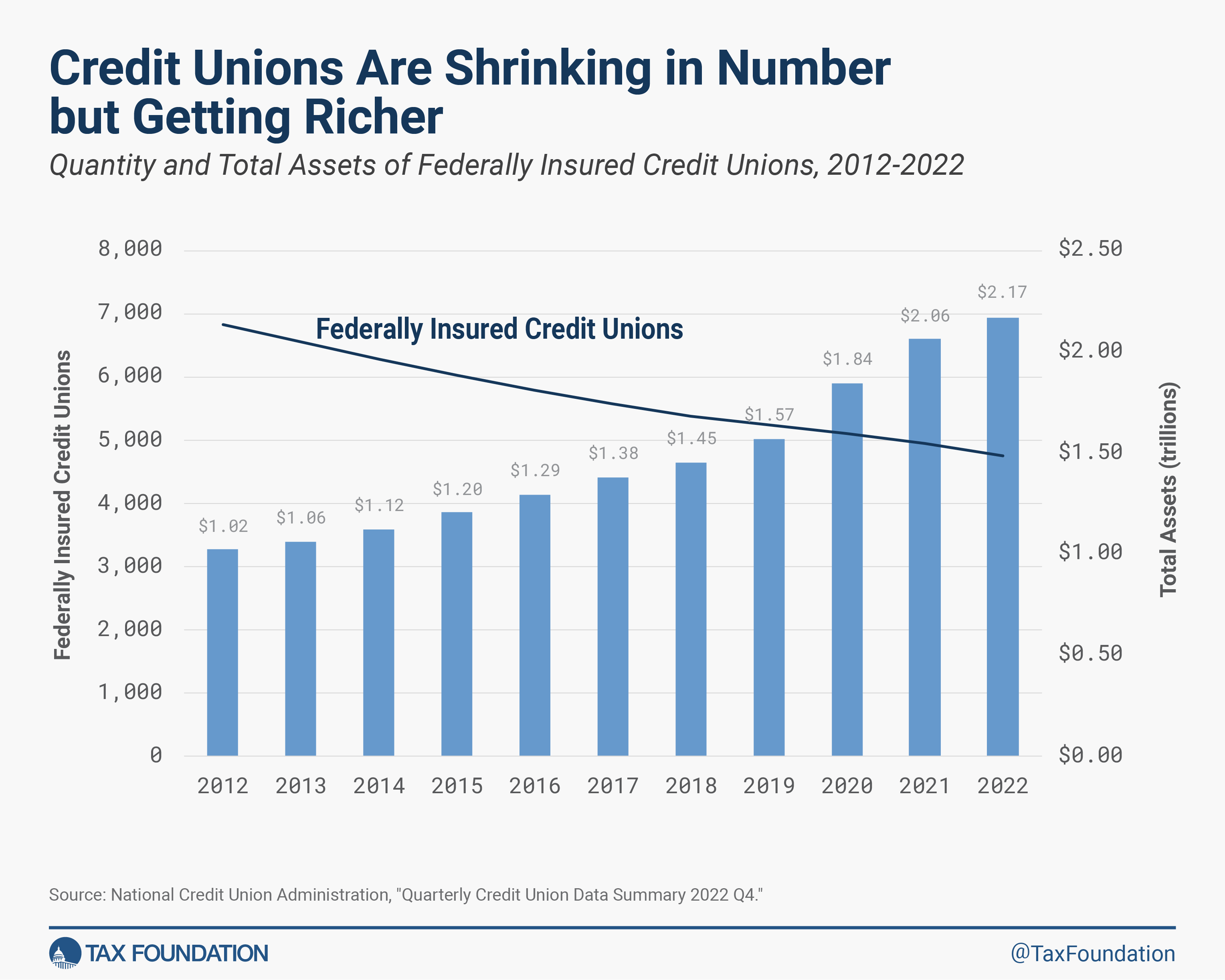

The price tag of the Inflation Reduction Act’s green energy tax credits is much higher than originally thought. This week, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) gave a new score as part of its analysis of House Speaker McCarthy’s debt ceiling bill—which would eliminate the credits—and pegged the cost of the credits at $570 billion from 2023 to 2033, roughly double its original estimate of $270 billion over 10 years. Among other things, this indicates the Inflation Reduction Act does not reduce deficits after all.

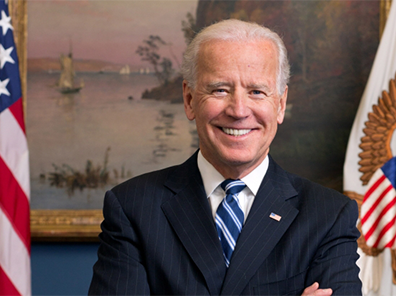

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has meant many things to many people. Last August, when it was being debated in Congress, it was sold as a way to ease inflation by reducing deficits. Initially, the CBO did find that it would reduce deficits by around $260 billion over 10 years (about 1 percent of the $18 trillion of deficits projected to occur under current law over the same period). Soon after enactment, the administration began marketing it as the “most significant climate legislation in U.S. history” because of the extraordinary generosity of about two dozen tax credits aimed at green energy technologies.

The Biden administration’s efforts to pitch the Inflation Reduction Act as a big “investment” in climate were always at odds with the deficit reduction idea. Over time, it became apparent that certain features of the credits could balloon their budgetary cost. For instance, the bill allows transferability between taxpayers to allow the credits to be fully monetized, and loose legislative language has allowed the Biden administration’s Treasury Department to expand eligibility and use through regulatory guidance.

For example, a recent Treasury ruling allows taxpayers to avoid the legislation’s eligibility limits for the $7,500 electric vehicle (EV) tax credits. Congress designed the rules to prevent people earning more than $300,000 from getting the credits and further limited them to apply only to cars with a sales price below $55,000 and SUVs and trucks with a sales price below $80,000. Treasury ruled that these, and other limits regarding domestic content requirements, don’t apply to leased vehicles. Unsurprisingly, leasing has now grown to about 34 percent of EV sales, compared to about 7 percent last September.

Though the CBO score of the credits has nearly doubled, it remains lower than many other estimates from outside experts. Researchers at Brookings Institution put the cost of the credits closer to $1 trillion over 10 years. Those estimates indicate the IRA bill as a whole increases deficits by several hundred billion over 10 years. It’s probably time for the CBO to provide a new score of the entire IRA bill so lawmakers and taxpayers understand what we’ve gotten ourselves into.

Here are a few things we know about the Inflation Reduction Act today:

- It doesn’t reduce deficits and may substantially increase deficits (CBO should rescore it).

- The energy credits drive the out-of-control cost of the IRA, showing the dangers of this kind of open-ended (non)budgeting.

- The energy credits are a boon for wealthy individuals with a preference for climate-oriented luxury goods, including expensive EVs and solar panels.

- The energy credits also benefit large corporations. For instance, the Joint Committee on Taxation recently analyzed two of the business credits that were extended as part of the IRA, finding that corporations with gross receipts of more than $25 billion in 2020 received about $3.7 billion, or 53 percent, of the Section 48 Energy Credit and about $4.6 billion, or 62 percent, of the Section 45 Credit for Electricity Produced from Certain Renewable Resources.

- Distributional analysis of the energy credits indicates high-income earners are the big winners. For example, based on analysis by the Tax Policy Center that allocates the business credits to shareholders and workers, and using updated revenue estimates, Jason Furman finds that the credits will provide a benefit of more than $11,000 for the top 1 percent of earners in 2027, raising their after-tax incomes by 0.5 percent. In contrast, the bottom quintile of earners receives a benefit of less than $100, raising their after-tax incomes by 0.3 percent.

- The energy credits add to the tax code’s complexity, increasing confusion and compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative challenges for the IRS.

- The tax hikes in the IRA, including the book minimum tax and stock buyback tax, were designed to pay for some of the costs of expanded credits, but are introducing a variety of uncertainties and compliance costs for business taxpayers. The book minimum tax suffers from many flaws, including the fact that book income is not a well-defined tax base, and so it requires voluminous regulatory guidance and taxpayer comments to try and sort out how it could possibly work. Meanwhile, the guidance continues to roll out even as the new tax liabilities are due, and many outstanding issues, such as how small partnerships are affected, will probably need to be settled in the courts. The stock buyback tax is another new idea in taxation, but not a good one. Ostensibly aimed at perceived problems in corporate finance, in practice it is also proving to be a way the administration can selectively punish certain types of firms and create additional compliance costs.

One unanswered question about the IRA credits is whether they would benefit taxpayers at all. Many countries are adopting the global minimum tax rules, and those rules allow countries to apply top-up taxes when a company has an effective tax rate below 15 percent, even if the low-tax income is beyond the enforcing country’s borders. If the credits are included in that calculation, then their value could be directly offset by tax increases in countries that have adopted the minimum tax. So, the U.S. would be giving a credit while another country gets more tax revenue through the top-up tax.

So far, it seems that at least some of the IRA credits will trigger foreign top-ups.

Speaker McCarthy’s efforts to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act’s energy credits are a step in the right direction and would constitute a real improvement in the tax code while substantially reducing deficits. If lawmakers want to address climate change, there are proven ways to do that in a more fiscally responsible manner by raising the cost of carbon emissions through some form of carbon pricing, such as a carbon tax. Carbon pricing is a standard and effective approach used in 47 countries, and it generates substantial tax revenues.

Resolving the debt crisis, including lifting the debt ceiling, will require policymakers to put political slogans aside and be straight with taxpayers about the drivers of the debt and proven ways to effectively address it. That includes recognizing when past legislation, such as the IRA green energy credits, has simply become too costly to continue.