PTAB Renders Decisions in Interference No. 106,127 | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

On September 28, 2022, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board denied all preliminary motions by Junior Party the University of California, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (collectively, “CVC”) and Senior Party ToolGen in Interference No. 106,127.

On the same day, the Board suspended further proceedings in this interference (and in Interference No. 106,126 between Junior Party the Broad Institute, Harvard University and MIT (collectively, “Broad”) and Senior Party ToolGen) “in the interest of not wasting resources” (see “PTAB Suspends ToolGen Interferences”), reasoning foreshadowed in the first portion of their decision on motions which notes that the Board’s judgment in the ‘115 Interference is binding for the purposes of this interference even though the decision is on appeal. But because the Federal Circuit has not overturned the Board’s earlier judgment, the panel continues (again “in the interests of efficiency”) in preparation for the now-suspended priority phase of this interference.

As a reminder, the parties had filed the following motions:

• For CVC, Substantive Motion No. 1 for priority benefit to U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/652,086, filed May 25, 2012 (“P1”), U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/716,256, filed October 19, 2012, (“P2”), and U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/757,640, filed January 28, 2013 (“Provisional 3”); Substantive Motion No. 2 to deny ToolGen benefit of priority to U.S. Provisional Application No. 16/717,324, filed October 23, 2012 (“P1”); Substantive Motion No. 3 asking the Patent Trial and Appeal Board to add claims in ToolGen’s U.S. Patent No. 10,851,380 to this interference; and Contingent Responsive Motion No. 1 to be accorded benefit of priority to U.S. Patent Application No. 13/842,859, filed March 15, 2013, or in the alternative U.S. Patent Application No. 14/685,504, filed April 7, 2015, or U.S. Patent Application No. 15/138,604, filed April 26, 2016.

• ToolGen filed Substantive Motion No. 1 for priority to later-filed U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/837,481, filed June 20, 2013 (“P3” or “ToolGen P3”), or alternatively, International Application No. PCT/KR2013/009488, filed Oct. 23, 6 2013 (“PCT”), contingent on the Board granting CVC Substantive Motion No. 2 to deny ToolGen benefit of priority to U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/717,324, filed October 23, 2012 (“P1”), and Substantive Motion No. 2 to deny CVC priority to its U.S. Provisional Application No. 61/757,640, filed January 28, 2013 (“Provisional 3”).

The Board’s opinion does not address the parties’ motions in order but starts with Junior Party CVC’s Motion No. 1 to be accorded benefit to the P1 and/or P2 provisional applications. The Board denied this motion based on its decision in Interference No. 106,115 on a related motion and the principle of issue preclusion based inter alia on the identify in scope of the interference count in this interference with the scope of the interference count in the ‘115 Interference, citing Lawlor v. National Screen Serv. Corp., 349 U.S. 322, 326 (1955). Citing Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 329 (1979), the Board asserts that ToolGen being CVCs opponent in this interference does not negate their application of the issue preclusion doctrine, which is based on “whether an issue of law or fact has been previously litigated,” citing International Order of Job’s Daughters v. Lindeburg & Co., 727 F.2d 1087, 1091 (Fed. Cir. 1984), and as it did in the ‘126 interference under similar circumstances, Mother’s Restaurant, Inc. v. Mama’s Pizza, Inc., 723 F.2d 1566, 1569 (Fed. Cir. 1983). Because CVC’s Motion No. 1 satisfies all the requirements for the Board to apply issue preclusion in this instance, citing A.B. Dick Co. v. Burroughs Corp., 713 F.2d 700, 702 (Fed. Cir. 1983), the Board denied this motion, with the opinion addressing and rejecting CVC’s arguments to the contrary (e.g., that the determination of priority is distinct from determination of benefit and thus the principle is not applicable because the earlier decision was not necessary for the earlier judgment; the Board asserted that the issue before it here is the same as the issue before the Board in the ‘115 Interference and thus the principle was properly applied).

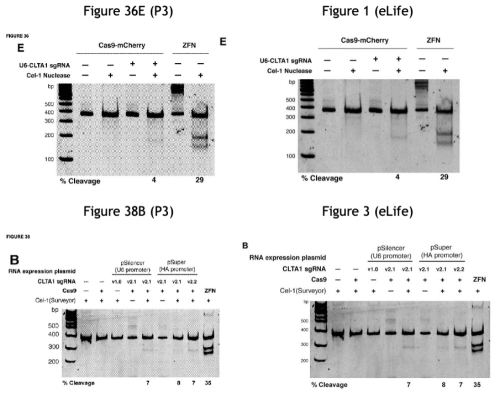

The opinion next addressed ToolGen Motion No. 2 to deny CVC benefit of its P3 provisional application. ToolGen’s argument as understood by the Board was that CVC did not show in P3 that its CRISPR-Cas9 system was “capable of cleaving or editing the target DNA molecule or modulating transcription of at least one gene encoded by the target DNA molecule” or that “meditate[s] double stranded cleavage at the [DNA] target sequence.” Citing its decision denying priority benefit to CVC’s P1 and P2 provisional applications, the Board notes that it provided two alternatives regarding possession sufficient to support priority benefit: “experimental evidence of possession of an embodiment of Count 1” or in the alternative “instructions or discussion of conditions that would have been considered to hinder activity in eukaryotic cells.” ToolGen’s arguments were unpersuasive for the Board because they focused only on the first alternative according to the opinion. The question for the Board was whether a person of ordinary skill would have considered CVC’s P3 provisional application to show possession of an embodiment of Count 1 under the second alternative basis. Regarding this the Board performed a comparison of the P3 disclosure with what CVC’s inventors (Jinek et al.) disclosed in a contemporaneous scientific publication. This comparison was directed to Example 2 of the P3 application (which ToolGen specifically argued was insufficient, supported by expert testimony) and associated Figure 36E and 38B (the latter being particularly called out by ToolGen for having bands significantly differing in size or position from what was expected if cleavage had been successful). While CVC countered with its own expert, what was ultimately persuasive to the Board (and fatal to ToolGen’s motion) was this comparison between Figure 36E and Figure 38B in the P3 provisional application with figures in a paper published in eLife on January 29, 2013 (“the day after CVC P3 was filed” according to the opinion):

To the Board, “[t]he bands in Figure 36E of CVC P3 and Figure 1E of the e-Life manuscript appear to be at least similar” and “[a]s with Figure 36E of CVC P3 and Figure 1E of the e-Life manuscript, the bands of each figure [38B and 3] appear to be similar.” Further, the Board considered the opinion of the peer reviewers of the eLife manuscript, that:

This excellent paper demonstrates the capability of a method based on the bacterial CRISPR-Cas system to introduce targeted, mutagenic double-strand breaks into human chromosomal DNA. This system could become a powerful alternative to protein-based targeting reagents, because it is based on simple Watson-Crick recognition and no protein design is required. To put this into perspective, the first proof-of concept study with zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) in human cells targeted plasmid, not chromosomal DNA [emphasis in opinion].

The Board concludes that “[t]hus, the reviewers, persons of ordinary skill in the art at the time CVC P3 was filed, considered the gels depicted in Figures 38B and 36E to contribute to evidence of a CRISPR-Cas9 system that successfully cleaved DNA within eukaryotic cells, noting ‘the paper demonstrates’ this and the study ‘show[s]’ it. While agreeing with ToolGen that Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 19 1357–58 (Fed. Cir. 2010), requires an applicant to show possession of the claimed invention, the Board emphasizes that the possession test requires “an objective inquiry into the four corners of the specification from the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art” (emphasis in opinion). The similarity of the disclosure in P3 and the eLife publication, and the publication reviewer’s assessment of the science disclosed therein, was sufficient to convince the Board that the CVC inventors possessed the invention and were entitled to priority benefit to the P3 provisional application. Accordingly the Board denied ToolGen’s Motion No. 2.

The Board dismissed CVC’s Responsive Motion No. 2 because it was contingent on the Board granting ToolGen’s Motion No. 2 and in view of its denial the Board dismissed this motion as moot.

Turning to CVC Substantive Motion No. 2, to deny ToolGen priority benefit to its P1 provisional (in some ways the most significant motion, because grant of this motion would make CVC the Senior Party) the Board denied the motion because while ToolGen did not provide a constructive reduction to practice of an embodiment of a eukaryotic CRISPR Cas9 system encoded by a codon-optimized Cas9 protein-encoding nucleic acid (as recited in ToolGen’s half of MacKelvey Count 1 as declared), the CVC half of the Count had no such requirement. The legal basis for this decision, as set forth by the Board, was that “priority of the filing date of a prior application in an interference is granted with respect to counts not claims; all that is necessary for a party to be entitled to benefit of an earlier filed application for priority purposes is compliance with 35 U.S.C. § 112 with respect to at least one embodiment within the scope of 22 the count” (emphasis in opinion), citing Falko-Gunter Falkner v. Inglis, 448 F.3d 1357, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 23 2006), and Hunt v. Treppschuh, 523 F.2d 1386, 1389 (C.C.P.A. 1975). The Board rejected CVC’s reliance on “judicial estoppel” (based on positions ToolGen had taken during ex parte prosecution of ToolGen’s utility application involved in this interference) because the standard is whether ToolGen showed reduction to practice of an embodiment within the Count, and here the Count included a portion that did not require codon-optimized Cas9 protein-encoding nucleic acid. As stated in the opinion, “[t]he purpose of an interference count is to provide the description of the interfering subject matter that sets the scope of admissible proofs on priority,” citing 37 C.F.R. § 41.201 and Slip Track Sys., Inc. v. Metal-Lite, Inc., 304 F.3d 1256, 2 1263 (Fed. Cir. 2002). As a practical matter, the Board recognized that “[i]f the parties were limited to their own ‘half’ of a count, the scope of admissible proofs could differ for each, making a determination of priority for a common invention problematic.” To CVC’s accusations of unfairness, the Board stated that “CVC did not request authorization to argue that Count 1 should be changed to refine the boundaries of the parties’ commonly invented subject matter[, n]or did CVC request authorization to argue that the parties’ claims do not interfere.” Except for these arguments, the opinion notes, “CVC does not argue that the ToolGen P1 application fails to describe an embodiment within the scope of Count 1” and further rejected CVC’s argument that ToolGen should be estopped from asserting a constructive reduction to practice. Accordingly, the Board denied CVC’s Motion No. 2, leaving the status of the parties undisturbed.

As it had for CVC’s Responsive Motion No. 2, the Board dismissed as moot ToolGen’s Motion No. 1 for priority benefit to applications later-filed than its P1 provisional application because it was contingent on grant of CVC’s Substantive Motion No. 2 (which the Board denied).

The Board also denied CVC’s Motion No. 3 to add claims of ToolGen Patent No. 10,851,380 to the interference. The only distinction between these claims and the Count was the addition of two guanine residues (“GG”) at the 5′ end of the guide RNA, and CVC argued that this difference would be obvious in view of the Jinek reference. The Board rejected many of ToolGen’s arguments, particularly with regard to uncertainty in the art regarding eukaryotic CRISPR on the grounds that the Count recites eukaryotic CRISPR and the analysis here considers whatever is recited in the Count to be prior art. Nevertheless, CVC’s arguments attempting to rebut ToolGen’s evidence of unexpected results (regarding decrease in off-target effects) were equally unavailing and the Board accordingly denied CVC’s motion in view of that evidence. And while ToolGen’s evidence is somewhat thin (“a bare assertion that one of ordinary skill in the art would have found the results to be surprising and/or unexpected”), the Board finds that “CVC had an opportunity to put forth and cite contradictory evidence of how one of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the results reported in the ‘308 patent, including from the cross-examination of [ToolGen’s expert witness]” which it did not do (“Rather, CVC presents arguments about the nature of the comparison presented in the ‘308 patent, its nexus to the claims, and whether ToolGen appropriately relied on these results. As explained above, we are not persuaded by these arguments.”) On these grounds the Board denied CVC’s Motion No. 3.

Finally, the Board dismissed as moot the parties’ various motions to exclude or concluded it has no need to address parties’ objections to admissibility in view of their decisions to deny the parties’ motions.

The interference thus remains in the same posture between the parties as it was when declared, and the parties must await the outcome of CVC’s appeal in the ‘115 Interference. Unless the Supreme Court deigns to review the Federal Circuit’s judgment (which is very unlikely regardless of the substance of that judgment) the suspension will not be lifted until sometime next spring, and a decision reversing the Board’s awarding priority to Broad should result in the priority phase here ensuing.

![[Webinar] Practical Masterclass in Patenting AI at the EPO and USPTO – October 11th, 1:00 pm – 2:15 pm EDT | Rothwell, Figg, Ernst & Manbeck, P.C. [Webinar] Practical Masterclass in Patenting AI at the EPO and USPTO – October 11th, 1:00 pm – 2:15 pm EDT | Rothwell, Figg, Ernst & Manbeck, P.C.](https://jdsupra-static.s3.amazonaws.com/profile-images/og.16055_152.jpg)