PTAB Remains Hostile to Section 101 Appeals | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

There is ample evidence that patent examiner allowance rates vary dramatically from examiner to examiner and art unit to art unit.[1] This has resulted in the general understanding that there are “easy” examiners and “tough” examiners.

Naturally, there is little complaining about “easy” examiners (until you are defending against a patent with very broad claims, at least). But when patent attorneys stand around the coffee machine at work (or, more accurately, are on Zoom or Teams calls), there is a not small amount of eye rolling and wringing of hands over “tough” examiners.

Over the last several years, a particular type of “tough” examiner has emerged — one that will reject just about any claim as ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 . . . and never withdraw the rejection.[2] In other words, if you get a 101 rejection from one of these examiners, prosecution is basically over. Interviews don’t help. Arguments and amendments go nowhere, with the examiner engaging in vigorous goalpost-shifting.[3] More often than not, the natural habitats of such examiners are the verdant plains of technology centers 1600 and 3600.

The USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) is often a last resort for patent applicants who cannot afford further appeals to the federal judiciary. Therefore, should not the PTAB lay the judicial smack down on these errant plains-dwellers? If only.

Last year, we studied all substantive 101 decisions from the PTAB that came down in 2021. The results were puzzling, striking, and, not in small part, abysmal. The PTAB affirmed examiners’ 101 rejections 87.1% of the time, whereas the overall affirmance rate across all grounds of rejection was 55.6%. Why the discrepancy? The data does not provide that information, though it could be due to the notorious vagueness of the test set forth in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, the Federal Circuit’s conflicting case law, and/or the PTAB not following the USPTO’s 101 guidance.

Regardless of cause, the numbers do not lie. The PTAB is a brutal tribunal for applicants attempting to argue that an examiner’s 101 rejection is in error.

But was 2021 an outlier or a blip on the radar? Does the data from 2022 exhibit a similar affirmance rate or has there been a “regression to the mean” of sorts?

To answer this question, we once again reviewed every substantive 101 appeal decided by the PTAB in 2022. As was the case for the 2021 data, this required a particular search strategy as well as manually combing the text of each decision.

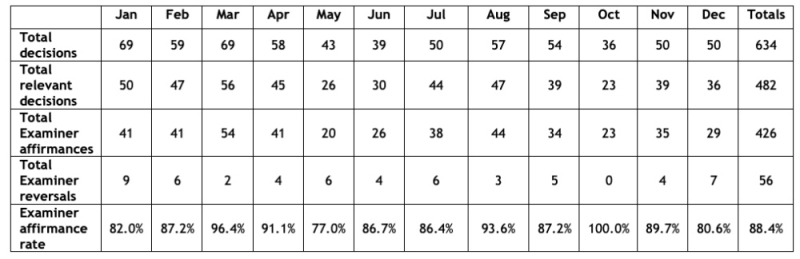

From the PTAB’s search interface, we specified the following criteria: decision dates between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2022, a proceeding type of “appeal”, a decision type of “decision”, and an issue type of “101”. Even so, the results were over-inclusive, returning decisions that just mentioned 101 in passing. Thus, we further filtered these decisions to focus only on those in which the applicant appealed an examiner’s Alice-based 101 rejection and the PTAB ruled on this grounds of appeal. This took the 634 decisions returned by the search engine down to 482 — the substantive 101 decisions.[4]

Of these, 426 were examiner affirmances, for an affirmance rate of 88.4%. Yep, the PTAB got a little worse for applicants in 2022. The month-by-month and total statistics are provided in the table below.

Not unlike 2021, the examiner affirmance rate fluctuated with no clear month-over-month trend. For example, the lowest 101 affirmance rate was in May (77%) while the highest was in October (100%).[5] Also like 2021, there is a slight downward trend in the number of appeals from Q1 to Q4. The monthly average of appeals on 101 grounds was 49.5 for the first four months of the year and 34.25 for the last four months of the year (as compared to 78.25 and 49.25, respectively, for 2021).

But one data point that sticks out is that the total number of appeals has dropped significantly year-over-year. In 2021, 708 substantive 101 decisions were handed down, while in 2022 this number was — as noted above — just 482. That is better than a 30% decline. From our (admittedly anecdotal) experience, this is not because examiners are getting easier. The opposite appears to be the case. It seems more likely that applicants have determined that appealing 101 rejections to the PTAB has betting odds akin to those of the Cleveland Browns making it to the Super Bowl.

Given that the PTAB does not provide much of a recourse for applicants stuck with a 101 rejection from an unrelenting examiner, we next wondered what grounds of rejection are popular with the PTAB. For the abstract idea exception to patentable subject matter, the three main categories are mathematics, mental processes, and methods of organizing human activity. In other words, a claim is deemed ineligible for patenting if it is directed to mathematics, a mental process,[6] or a method of organizing human activity[7] without significantly more.

Of all substantive affirmances of 101 rejections by the PTAB, 14.1% were based on mathematics, 58.4% on mental processes, and 64.6% on methods of organizing human activity. Use of the latter two categories is quite widespread among PTAB judges, with many decisions incorporating new grounds of rejection to accentuate the examiner’s mental process rejection with a method of organizing human activity rejection or vice-versa. Indeed, grounds of both mental processes and methods of organizing human activity were found in 31.9% of all affirmances.

Another factor we looked into was whether certain PTAB panels or judges were making formulaic rejections — in other words cutting and pasting large sections of their reasoning for the 101 rejections from case to case and only changing the discussion of the facts. It was not too difficult to identify a few instances of this.

For example, Appeal 2021-002509 (decided January 31, 2022) and Appeal 2021-002913 (also decided January 31, 2022) involve two different applicants claiming two different technologies, but the decisions rely on reasoning that is largely word-for-word the same. The deciding PTAB panels had two judges in common and both decisions were written by the same judge. Another example of liberal cutting-and-pasting can be found in Appeals 2021-002840 and 2021-002807, also both decided on the same day by a panel with two judges in common.

It is important to understand that this does not imply laziness or malfeasance on the part of anyone involved in these decisions. Instead, this is more evidence that it is very easy to find virtually any invention ineligible by robotically deconstructing the claims into small enough parts and ignoring the advantage or improvements provided the claims as a whole. Not convinced? Try our rationale for invalidating the eligible claims of Diamond v. Diehr that is based on observed USPTO reasoning.

There is a false narrative that has been floating around for the better part of two decades. It implies that broad claims on obvious technological variants can be easily obtained from the USPTO. There may have been some small truth to this notion in the 1990s, but today the pendulum has swung so far in the other direction that narrowly-scoped, complex, innovative technologies are often denied patentability just because they involve software.

As a consequence, the irrational arbitrariness of Section 101 provides limited access to patenting for individual inventors as well as small and mid-sized companies. Maybe someday the PTAB will lay the judicial smack down in a less one-sided fashion, but for now it appears that 101 appellants need to be wary against flying elbows of ineligiblity.

[1] See the histogram of examiner grant rates compiled by Patent Bots, for example.

[2] Okay, the word “never” is admittedly somewhat hyperbolic, but not far from the truth.

[3] Again, we want to emphasize that most examiners are reasonable, even with their 101 rejections. Some are quite clear in terms of what they deem to be sufficient to overcome a 101 rejection. But there is a notable contingent who are not, and anecdotally it seems as if the size of this contingent has grown since early 2021.

[4] Many of these decisions also reviewed rejections on other grounds (e.g., Sections 102 or 103). We did not consider anything but the 101 determinations. We also omitted rejections based on laws of nature or natural phenomena, which accounted for only 10 of the decisions and did not impact the results in any significant fashion.

[5] Ouch. Just ouch. At least relatively few appeals were decided in October.

[6] We have previously detailed how illogically and broadly that this category is being construed.

[7] This is another overly-broad category. What isn’t a method of organizing human activity at some level?

![[Event] Keeping Your Online Contests & Sweepstakes Legal – September 21st, Phoenix, AZ | Lewis Roca [Event] Keeping Your Online Contests & Sweepstakes Legal – September 21st, Phoenix, AZ | Lewis Roca](http://jdsupra-static.s3.amazonaws.com/authors/619bd413d2fab.200w.jpg?rand=62fadab4ddb41)