PTAB Decides Parties’ Motions in CRISPR Interference | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

Having heard oral argument at a hearing held on Monday, November 21st, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board on December 14th entered its decision on motions in Interference No 106,132 between Senior Party Sigma-Aldrich (“Sigma”) and Junior Party the University of California/Berkeley, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (collectively, “CVC”).

Sigma had one substantive motion at issue (Substantive Motion No. 1), a motion to change the Count, and CVC had three substantive motions (Motion No. 1 for priority benefit, Motion No. 3 to change the Count, and Motion No. 4 to add claims of Sigma Patent Nos. 10,731,181 and 10,745,716), and a contingent motion seeking priority benefit in the event that the Board grants Sigma’s Motion No. 1 to change the Count (Responsive Motion No. 1).

In its decision, the Board denied Sigma’s Motion No. 1, denied CVC’s Motions Nos.1 and 3, dismissed Responsive Motion No. 1 as moot (having denied Sigma’s motion), and granted Motion No. 4 (which prompted the Board to redeclare the interference to add these claims).

The opinion sets forth as an initial matter the circumstances surrounding the several interferences declared involving “similar subject matter” and CVC as a party, pointing out that its recent decision in Interference No. 106,115 (see “PTAB Grants Priority for Eukaryotic CRISPR to Broad in Interference No. 106,115”) awarded priority to The Broad Institute, Inc., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and President and Fellows of Harvard College (collectively, “Broad”). This decision prompted CVC to argue that the Board lacks jurisdiction because its decision is being appealed to the Federal Circuit, based inter alia on In re Allen, 115 F.2d 936, 941 (C.C.P.A. 1940). Sigma apparently agreed, citing 37 C.F.R. § 41.35(b)(2), albeit this rule “does not indicate that the Board lacks all jurisdiction over other proceedings involving the same claims, only that jurisdiction over the appealed decision ends” according to the Decision. The Board noted that while the Federal Circuit could overrule the Board on matters of law, “that hypothetical result has yet to come to pass” and accordingly the Board will decide the decisions on these preliminary motions “in the interest of efficiency” as justified by 37 C.F.R. § 41.1(b).

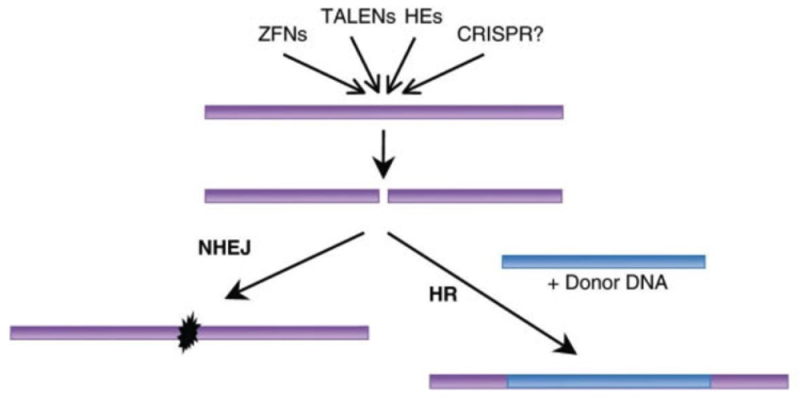

Regarding Sigma’s Motion No. 1, the Decision sets forth as the basis for the Board’s denial thereof Sigma’s failure to persuade them that the Count as declared encompasses more than one patentable invention and the Proposed Count (Count 2) encompasses only one, this being what is required for substitution, citing Lee v. McIntyre, 55 USPQ2d 1137, 1142 (BPAI 2000). In making its analysis of whether Sigma has satisfied its burden, the Board adopted the distinction drawn by Sigma between “cleavage plus integration” CRISPR embodiments (otherwise referred to in the art as homology-direct repair or HDR rather than non-homologous end joining or NHEJ) (which Sigma contended is recited in the portion of McKelvey Count 1 as declared that is derived from a Sigma claim-in-interference) and “cleavage” alone embodiments (also known as double-strand break or DSB embodiments) (which Sigma contended is recited in CVC’s portion of the McKelvey Count as declared). Sigma’s position is that these two embodiments are patentably distinct, and that the interference Count as declared encompasses more than one patentable invention. Sigma’s proposed Count 2 replaces the CVC claim recited in the Count as declared with one or another of three other CVC claims that recite “cleavage plus integration” CRISPR embodiments. In making its assessment, the Board applied the two-way test for interfering subject matter recited in 37 C.F.R. § 41.203(a) (and because the claim language differs makes its determination on obviousness grounds, citing In re Dow Chemical Co., 837 F.2d 469, 473 (Fed. Cir. 1988)). The Board made its decision based on whether the skilled worker would have had a reasonable expectation of success in the “cleavage plus integration” embodiment in light of the “cleavage only” embodiment, which the Decision notes is a question of fact under PAR Pharm., Inc. v. TWI Pharm., Inc., 773 F.3d 1186, 1196–97 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (the Board thus making any appeal of this decision more difficult in view of the deference courts must give to the PTAB’s factual determinations under Dickerson v Zurko). The Board also noted in its discussion of this standard that the required expectation of success “need be reasonable, not absolute,” citing University of Strathclyde, v. Clear-Vu Lighting LLC, 17 F.4th 155, 165 (Fed. Cir. 2021). The decision notes the difference between art that discloses only general instructions on how a particular technology can be practiced, citing Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc. v. Schering-Plough Corp., 320 F.3d 1339, 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2003) and situations where the art provides “specific instructions or success in similar methods or products” as in PAR Pharm. The Board reviewed Sigma’s arguments that NJEJ DNA repair routes following CRISPR cleavage were “far more common” than HDR and thus the skilled worker’s expectation of achieving its “cleavage plus integration” CRISPR embodiments would not have been reasonable at the time its invention was made, based on expert testimony. CVC proffered its own experts to provide contrary testimony, noted by the Board in the Decision. While noting certain deficiencies in CVC’s argument and testimony, the Decision also credits CVC with proffering persuasive testimony that HDR was used on DSBs arising from a variety of mechanisms, including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (and that Sigma did not adduce testimony challenging CVC’s experts’ assertions and conclusions in this regard). The Board concluded its discussion by asserting that the evidence taken as a whole does not support Sigma’s arguments regarding the reasonableness of the skilled worker’s expectation of success (including reference to other, more general but also unavailing Sigma arguments in this regard, many of which the Board disregarded because it considered the capacity for CRISPR cleavage to occur in eukaryotic cells to be assumed for the purpose of its analysis because it was recited in CVC’s portion of the Count that is the prior art from which the patentability of Sigma’s portion of the Count was assessed). Specifically discussed were purported uncertainties arising because the Cas9 protein remained bound to the cleaved DNA, but this did not support Sigma’s argument according to the Board because other cleavage enzymes capable of HDR were similarly still bound after cleavage. There was a similar level of discussion regarding production of blunt-ended versus overhanging-ended DSBs, with the Board stating that in this portion of the argument “[t]he preponderance of the evidence supports both Sigma’s and CVC’s positions.” Other Sigma arguments failed because in the Board’s view Sigma neglected to acknowledge that for the purposes of this analysis CVC’s portion of Count 1 was considered to be in the prior art (illustrating the sometimes-confusing artificiality of interference practice), as shown in a figure reproduced by a reference cited by Sigma in its argument:

The presence of the “?” with reference to CRISPR cleavage was enough in this context to disqualify the reference (a deficiency shared by other references cited by Sigma in support of its argument here).

The Board concluded this portion of its Decision by stating:

In light of the evidence both parties cite, we are not persuaded that one of ordinary skill in the art would have failed to reasonably expect the cleavage only CRISPR-Cas9 system of CVC’s portion of Count 1 to have been able to achieve integration of donor DNA by HDR as recited in the Sigma portion of Count 1. Accordingly, we are not persuaded by Sigma’s argument that a CRISPR-Cas9 system capable of cleavage and donor integration by HDR would not have been obvious over a CRISPR-Cas9 system capable of cleavage only. We are not persuaded that both systems are not the same patentable invention and that Count 1 should be limited to only the latter.

Turning to CVC’s Motions, the Board first took up CVC’s Motion No. 3 to change the Count (an appropriate parallel). The basis for this Motion was to limit CRISPR embodiments falling within the scope of Proposed Count 2 to utilize single guide RNA species (sgRNA), which is a limitation in CVC’s half of the McKelvey Count as declared. As in Sigma’s Motion No. 1, CVC uses a different Sigma claim that is limited to sgRNA embodiments in its Proposed Count 2. The Board rejected CVC’s argument that its Motion No. 3 should be granted to bring this interference into greater consistency with Interferences Nos. 106,115; 106,126; and 106,127 (the Decision noting that CVC did not cite Interference No. 106,133 pitting Sigma against Broad as justification for granting its motion), stating that “each of the counts include claims from different sets of parties. Because the claims in the different interferences are not identical and do not originate from identical specifications, the counts which embrace them need not necessarily be the same” and “different proofs could be appropriate in different interferences because the parties’ claims may encompass different inventions.” Regarding CVC’s assertion that the Sigma portion of the McKelvey Count as declared is ambiguous with regard to whether or not it is limited to sgRNA CRISPR embodiments, the Board disagreed with CVC that their Proposed Count 2 addresses the issue because the evidence CVC applied for interpreting the Sigma claim upon which Proposed Count 2 is based is not from Sigma’s priority provisional application designated P1 but rather from CVC’s scientific reference, Jinek et al., whereas Sigma’s argument against CVC’s Proposed Count 2 relies upon broadening language from its P1 application. In addition, the Board identified a claim differentiation issue wherein a dependent claim expressly recites dual molecule RNA embodiments of CRISPR. And CVC’s reference to the Board’s decision in the ‘115 Interference is similarly unavailing, the Decision stating that “[t]he claim interpretation in that interference, though, was of different claims, presented by a different party, originating from a different specification, and did not render any other dependent claim indefinite.” The Board’s appreciation of the totality of the evidence presented on this issue is simply stated that “we are not persuaded that Count 1 in this interference is limited to a single-molecule RNA configuration” and that “[w]e are not persuaded by CVC’s arguments to change the count because CVC fails to persuade us that a CRISPR-Cas9 system with a single molecule RNA configuration is not the same patentable invention as a CRISPR-Cas9 system with a dual-molecule RNA configuration (which of course is CVC’s basis for presenting this motion). (And in something of an aside the Decision states that “[a]lthough the separate patentability of a single-molecule RNA configuration and a dual-molecule RNA configuration has been asserted in other Board proceedings, the Board has never decided on the basis of persuasive evidence presented by any party that both configurations are or are not the same patentable invention.) Accordingly (and after addressing and dismissing CVC’s assertion of prejudice and preferential treatment for Sigma) the Board denied this motion.

CVC fared better with regard to its Motion No. 4 to add claims from Sigma’s U.S. Patents Nos. 10,731,181 (claims 1-17) and 10,745,716 (claims 2-4, 11, 14, and 21-22, the other claims in this patent having been disclaimed by Sigma) pursuant to 37 C.F.R. § 41.207(b)(2) and in satisfaction of the requirements of 37 C.F.R. 41.208(b). The Board was persuaded by CVC’s expert’s testimony (and Sigma’s failure to provide contradictory testimony) regarding the obviousness of choosing the particular nuclear localization sequence and its C-terminal localization, use of sgRNA embodiments, and the S. pyogenes source of Cas9 protein (CVC benefiting here from the presumption that CRISPR could be practiced successfully in eukaryotic cells). The Board characterized Sigma’s arguments as “attempts to support [their] argument with citations to many outdated rules and non-precedential Board opinions,” and applied instead current Board Rule 37 C.F.R. § 41.207(b)(2)(being “directly on point”), a “one-way test” of obviousness that CVC satisfied with its evidence and unchallenged testimony. The Board further rejected Sigma’s attempt to apply rules (such as 37 C.F.R. § 41.203(a) and § 41.202(a)(3)) that were directed to declaration of a new interference or wherein the claims are based on a new interference count. “Once that determination (that an interference should be declared) has been made . . . the determination of whether claims correspond to the count or not is made by a one-way test, under the guidance of 37 C.F.R. § 41.207b)(2)” according to the Decision. Finally, the Decision recognizes that Sigma improperly quoted an earlier, nonprecedential decision to support its argument, and that it asserted the Board had discretion to deny CVC’s motion, again based on prior interference rules no longer applicable. Accordingly, the Board found that the preponderance of the evidence supported CVC’s position and granted the motion.

Finally, amongst the parties’ preliminary motions the Board denies CVC’s Motion No. 1 for accorded benefit to its U.S. Provisional Application 61/652,086 (“CVC P1”), filed 25 May 2012 and U.S. Provisional Application 61/716,256 (“CVC P2”), filed 19 October 2012. The Board agreed with Sigma that this issue has been decided previously in the ‘115 Interference with regard to a McKelvey Count in that interference comprising the same CVC claim as in this interference, claim 156 of U.S. Serial No. 15/981,807. Under these circumstances, the Board applied the doctrine of issue preclusion in denying CVC’s Motion No. 1, citing A.B. Dick Co. v. Burroughs Corp., 713 F.2d 700, 702 (Fed. Cir. 1983); International Order of Job’s Daughters v. Lindeburg & Co., 727 F.2d 1087, 1091 (Fed. Cir. 1984), and Mother’s Restaurant, Inc. v. Mama’s Pizza, Inc., 723F.2d 1566, 1569 (Fed. Cir. 1983), as controlling Federal Circuit precedent (in addition to the Court’s decision affirming the Board’s determinations on this issue in Interference No. 106,048). CVC having had a “full and fair opportunity to litigate the same benefit issue” in the ‘115 Interference the Board states that “we are not persuaded that CVC should be given an opportunity to present new evidence on the identical issue” in this interference.

The Board also denied as moot CVC’s Miscellaneous Motion to exclude Sigma evidence because the Board’s Decision did not rely upon this evidence.

The Board announced at the end of its Decision that it would redeclare the Interference. Unannounced but concomitant with redeclaration, the Board suspended proceedings into the Priority Phase in view of the Board’s Decision in the ‘115 patent being under Federal Circuit review. These developments will be the subject of a later post.