Parolees Paroling In More Parolees

My colleague Todd Bensman recently reported on the 320,000 foreign nationals (including Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans) who were allowed to fly to the United States and released on “parole”. Immigration parole is not a visa, it is a mere “official permission to enter and remain temporarily in the United States” and does not constitute a “formal admission under the U.S. immigration system.”

Many of the foreign nationals who flew here and were granted parole upon arrival were “privately” sponsored into the United States under a program called the “Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans. This is one of the many programs the Biden administration designed to facilitate “legal” access to the United States in order to deter illegal entries (though it is clearly not working). Moreover, these programs characterized as using “private sponsorship”, meaning a private individual – including a foreign national – agrees to pay for another to follow and stay here, though such an agreement can, in fact, be fueled by federal funds (i.e., taxpayer dollars).

The “Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans” allow foreign nationals (of any nationality) who have “temporary authorization” to remain in the United States – such as on parole – to sponsor other foreign nationals in turn to come here on parole.

Under this process, U.S.-based sponsors do not need to be U.S. citizens or permanent residents (i.e. green card holders) or even have a formal legal status.

U.S.-based sponsors can be here on parole. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) uses its “discretion” to authorize parole. Parole allows individuals, “who may be inadmissible or otherwise ineligible for admission”, to be released into the United States for a temporary period. Those paroled in are not being “formally admitted into the United States for purposes of immigration law.” Yet, those granted parole can now decide who gets to join them here “temporarily” under parole. Most of us are aware of the permanent nature of the temporary status held by migrants here, especially under the Biden administration.

. . . or on Temporary Protected Status (TPS). TPS is a designation that “gives immigrants time-limited permission to live and work in the United States and avoid potential deportation.” Yet someone with a “limited permission to live here” can now sponsor a foreign national into the United States. The Biden administration has greatly expanded those who are eligible for TPS.

. . . or on Deferred Enforced Departure (DED). Although DED is “not a specific immigration status, individuals covered by DED are not subject to removal from the United States for a designated period of time.” So those who are granted DED, which is a benefit “authorized at the discretion of the President of the United States that protects certain individuals from deportation” and allows them to live here “temporarily”, can now sponsor and decide who gets to join them and live in the United States.

. . . or on Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). DACA “temporarily delays the deportation of people without documentation who came to the U.S. as children.” Note that DACA is being challenged in court, and as a result, “DHS is prohibited from granting initial DACA requests and related employment authorization under the final rule.” Yet, DACA recipients can now give U.S.-entry tickets to migrants of their choosing

Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans

The program allows Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans and their family members (of any nationality) to be released into the United States on parole (for an initial period of two years, renewable) and apply for employment authorization, provided U.S.-based supporters (sponsors) agree to provide them with financial support during their stay here.

A “U.S.-based supporter” need not be a U.S. national, citizen, or lawful permanent resident (green card holder); other individuals present in the United States can also act as a sponsor under this new process. Examples of individuals who meet the supporter requirement include:

- U.S. citizens and nationals;

- Lawful permanent residents, lawful temporary residents, and conditional permanent residents;

- Nonimmigrants in lawful status (who maintain their nonimmigrant status and have not violated any of the terms or conditions of their nonimmigrant status);

- Asylees, refugees, and parolees;

- Individuals granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS); and

- Beneficiaries of deferred action including Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or Deferred Enforced Departure (DED).

The “Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans” is modeled on the “Uniting for Ukraine” program designed by the same administration following the Russian invasion to offer Ukrainians a chance to come to the United States via parole. These programs are presented as “private”, non-taxpayer-funded sponsorships, except that they could, in fact, benefit from taxpayer money.

Here’s how. Even though only one U.S.-based supporter can complete and file online Form I-134 (Declaration of Financial Support) on behalf of one beneficiary, they can do so “in association with or on behalf of an organization, business, or other entity that will provide some or all of the necessary support to the beneficiary.” Multiple supporters (including representatives from various human rights and refugee advocates organizations) can therefore agree to come together and share responsibility to support a beneficiary and facilitate approval. In such a case, the supporter who files a Form I-134A should include supplementary evidence demonstrating the identity of, and resources to be provided by, the additional supporters. Furthermore, individuals “who are filing in association with an organization, business, or other entity do not need to submit their personal financial information, if the level of support demonstrated by the entity is sufficient to support the beneficiary.” (Emphasis added.)

So, financial support can come from organizations such as refugee resettlement agencies and their local affiliates that are, in turn, mostly funded by U.S. government contracts. In the end, U.S. tax dollars that go to resettlement contractors can in turn be used as additional support in the Declaration of Financial Support form submitted to admit the beneficiary into the United States.

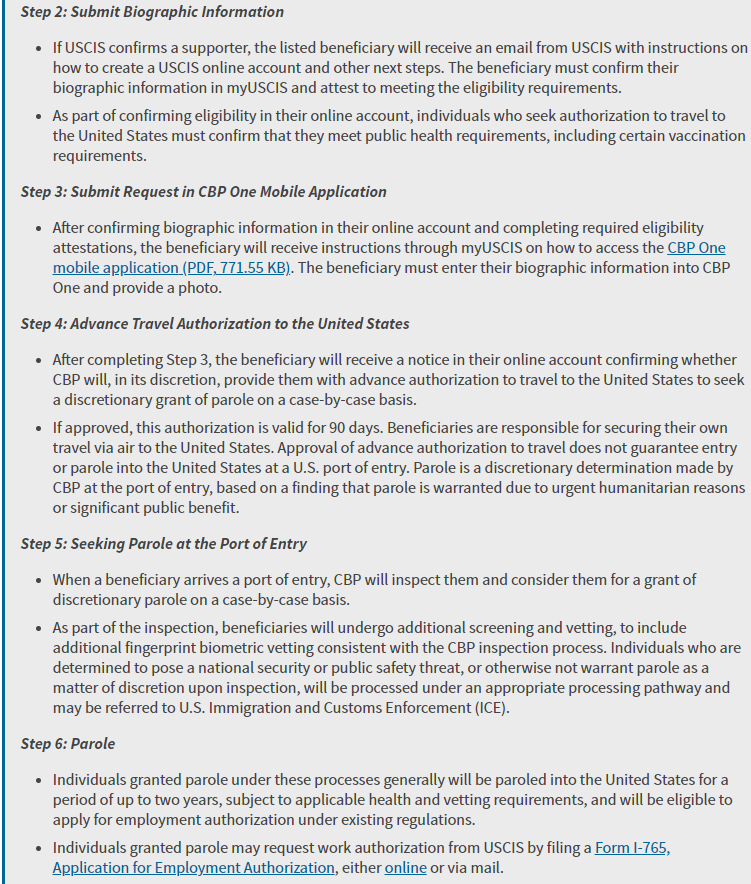

Addressing the issue of financial support is Step 1 in the process, as outlined on the USCIS website. The subsequent steps are:

Some final thoughts.

The Biden administration’s plans to expand “access to safe, orderly, legal migration pathways” in accordance with the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) anchored in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, are also based on the directives of the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants that was adopted by UN member states (including the United States under the Obama administration).

The plan to discourage migrants from “putting their lives in the hands of dangerous smugglers and traffickers” by offering other “legal” pathways is obviously not working, with hundreds of thousands still illegally crossing every year.

Another point to be underlined here pertains to the geographical aspect of settlement. Just like refugees who are “privately” sponsored under the Welcome Corps program (a new initiative launched by the Biden administration under the refugee resettlement program to allow private individuals in the United States to select their own refugees and future American citizens), these Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan parolees are flying straight into American communities without the knowledge of state and local officials or residents.

Under the regular refugee resettlement process, the reception and placement of refugees is determined by resettlement agency representatives. Since initial resettlement services are provided to newly arriving refugees by a local affiliate of one of the participating resettlement agencies, refugees are usually not resettled in states that do not have any local affiliates. This geographical “obstacle” has now been shattered with the private sponsorship of refugees under the Welcome Corps.

Similarly, parolees under the “Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans” can fly and settle in any American community without prior notice and under the radar. America’s airspace and communities are wide open for them.

One last point pertains to the extensive use of parole by the Biden administration.

Parole authority under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A) grants discretion to DHS to temporarily parole an alien into the country “only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” The problem is that, as the Congressional Research Service recently put it, the statute “does not define urgent humanitarian reasons, significant public benefit, or case-by-case basis, leaving substantial debate over the manner in which the executive branch exercises discretion in invoking what is commonly known as humanitarian parole authority.”

The legality of the Biden administration’s extensive use of parole has been widely questioned, including by my colleagues George Fishman, Andrew Arthur, and Elizabeth Jacobs. What is equally, if not especially puzzling, is that this administration is transferring power to parolees (who, supposedly, are here on a provisional, short-term basis) by allowing them to pick who gets to join them in the United States, to live and work here, under that same illusory, “temporary”, and highly ambiguous status.