PA Corporate Tax Cut: Details & Analysis

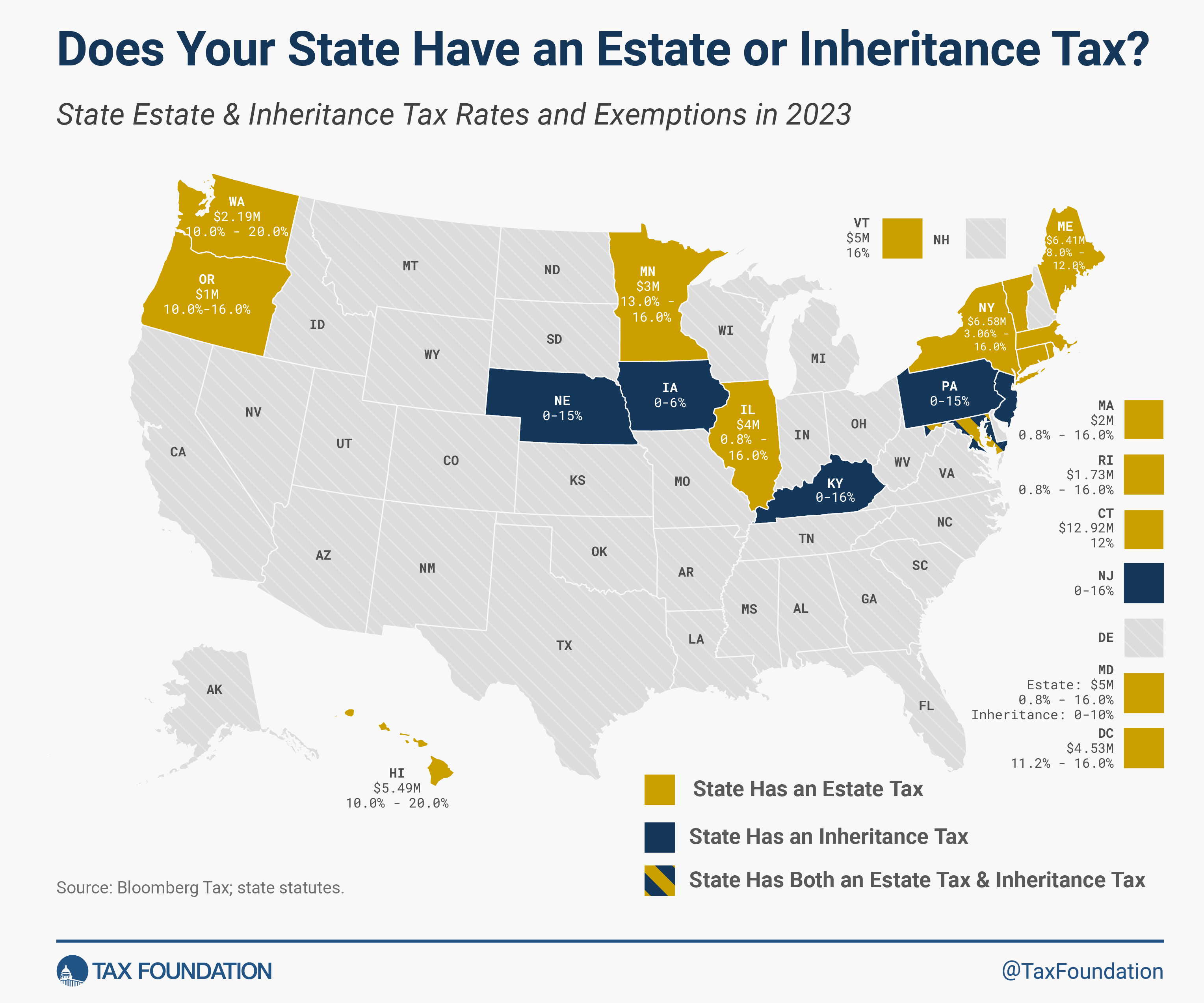

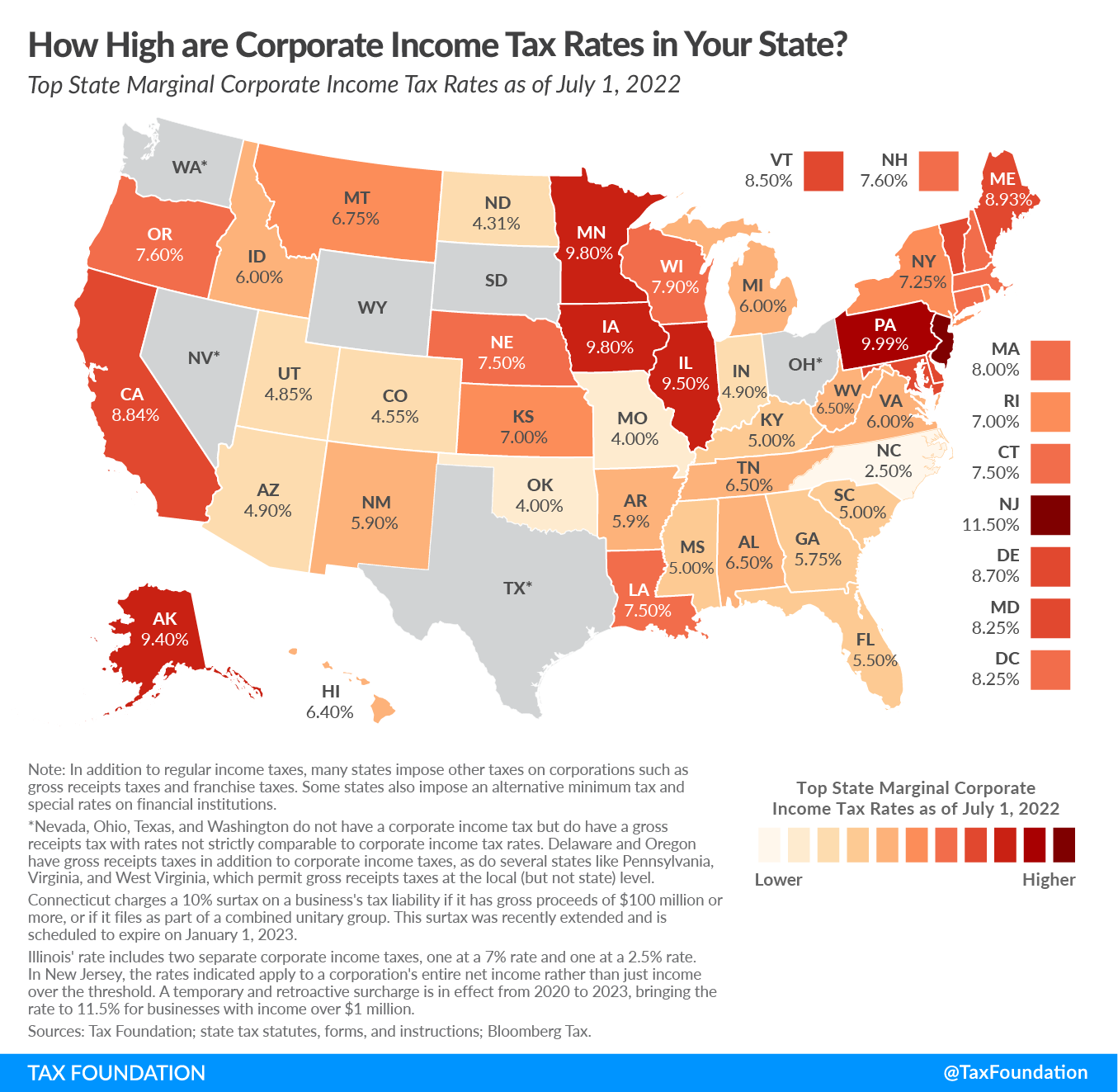

Over the past decade, policymakers from both parties in Harrisburg have proposed reducing Pennsylvania’s 9.99 percent corporate net income tax (CNIT) rate but could not agree on an approach—until now. With enactment of HB 1342 as part of the 2022-2023 state budget, lawmakers finally succeeded in cutting what had been the second highest state corporate tax rate in the nation.

Beginning January 1, 2023, the Pennsylvania corporate net income tax rate will decrease 1 percentage point to 8.99 percent. Each year thereafter the rate will decrease 0.5 percentage points until it reaches 4.99 percent at the beginning of 2031. Additionally, the law includes a provision that will increase the amount of capital investment pass-through business owners can deduct on their individual income tax returns the year the investments were made. The legislation leaves a few things to be desired, but overall, Pennsylvanians will be well served by the reforms the law sets in motion.

In June, the Tax Foundation testified before a committee of the Pennsylvania legislature regarding how structural tax reforms could benefit Pennsylvanians navigating the challenges of inflation. Several of the recommendations, including cutting the corporate net income tax rate and increasing the amount of capital investment that could be immediately expensed, were included in the final version of HB 1342.

Unlike policies that provide near-term financial relief (like tax holidays, direct cash transfers, or rebates), these structural tax reforms can help the state’s economy respond to inflationary demand. Moreover, the reforms will continue to yield economic benefits after the inflationary period has waned.

The eventual depth of the CNIT cut in HB 1342 exceeded those of House and Senate bills—7.99 percent and 5.99 percent, respectively—that passed in their originating chambers earlier this year. Governor Tom Wolfe (D) had proposed a 4.99 percent CNIT rate that would have been largely offset by an aggressive quasi-combined reporting structure. It would have added complexity and uncertainty to the Commonwealth’s tax structure while limiting the benefit of the rate reduction. The final version of HB 1342 included the governor’s rate but excluded his addback plan. When fully implemented, the new 4.99 percent rate could be the seventh lowest corporate rate in the country.

Until passage of HB 1342, Pennsylvania’s tax code also contained a uniquely large bias against small business expenses associated with investing in machinery, equipment, and other short-lived capital assets. Instead of those expenses being deductible in the year they occurred, the Pennsylvania tax code required most of them to be deducted over time according to a depreciation schedule. At the federal level, Section 179 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) lets small business owners offset the cost of investment by allowing the deduction of up to $1 million of investment in the year the investments were made. Most state allowances conform to this standard, but Pennsylvania only allowed $25,000 in immediate expensing of Section 179 property. That was tied for the smallest amount in the country.

With enactment of HB 1342, the Commonwealth now conforms to the inflation-adjusted $1 million federal deduction allowance. This is a positive development for small business owners and their employees as additional capital formation increases productivity, encourages wage growth, and increases output—all necessary at the state level to combat inflation and ward off the worst effects of a looming recession. Enacting well-designed net operating loss (NOL) provisions for pass-through businesses would also contribute to those ends. Although NOLs were not addressed in HB 1342, there are many compelling reasons to reengage that subject in future legislation.

The combined impact of the CNIT rate reduction and Section 179 expansion are perhaps best illustrated by the change in Pennsylvania’s ranking on our State Business Tax Climate Index. Prior to passage of HB 1342, Pennsylvania’s overall structural ranking was 29th out of 50. The individual income tax structure ranked 19th, and the corporate income tax structure ranked 44th. In 2023, the Commonwealth will rank 23rd overall.

Passage of HB 1342 was a good start to making the Commonwealth competitive again, but nothing is inevitable until it happens. If there is a downside to the reforms of HB 1342 it is the nine years it will take for the CNIT rate to reach 4.99 percent. On the one hand, several states with formerly high rates have followed the incremental-annual-reduction model. In that sense, Pennsylvania’s elongated reform design is not unique or necessarily cause for concern. On the other hand, the sluggish pace of CNIT reductions evokes memories of Pennsylvania’s phaseout of the capital stock and franchise tax (CSFT), which was haphazardly paused and restarted for years before finally being eliminated.

The legislature had the opportunity to make a bold cut to the CNIT rate this year and to structure opportunities for future rate cuts around well-designed revenue triggers. Instead, the Commonwealth will enter 2023 with a CNIT rate that will still be fifth highest in the nation. Under this design, it could take several years before rates are competitive enough to entice corporations back to the Keystone State.

In the meantime, lawmakers should resist the temptation to treat CNIT reform with the same skepticism as CSFT elimination. Rather, they should continue to advance structurally neutral, free-market-enhancing tax legislation in the spirit of Indiana, Iowa, and North Carolina. These states also started with incremental alterations, but each year they improved on or accelerated the tax reforms enacted in previous legislative sessions.

Indiana has consistently chipped away at its corporate income tax (CIT) rate over the last 10 years. In 2012, the CIT rate was 8.5 percent. Today it is 4.9 percent. Iowa passed comprehensive tax reforms in 2018 and then accelerated those reforms with surplus revenue in 2022. Once fully phased in, Iowa will have a more neutral tax base, a flat individual income tax rate of 3.9 percent (down from 8.98 percent), and a flat corporate income tax rate of 5.5 percent (down from 12 percent). These reforms have positioned Iowa to improve from the fifth-worst-structured tax code before 2018 to the 15th-best-structured tax code once reforms are fully phased in. For its part, North Carolina enacted comprehensive tax reform in 2013 and then built on those reforms in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2021. Pennsylvania should follow suit.

Pennsylvanians should be encouraged by the reforms this legislation has set in motion. If the reforms of HB 1342 were fully implemented today, Pennsylvania’s corporate structure would rank 27th out of 50, a drastic improvement from its current 44th. The Commonwealth’s overall tax competitiveness ranking would improve to 17th from 29th.

To maximize the benefits of the present reforms, the legislature should consider accelerating the CNIT rate reductions. Then, to amplify their effect, policymakers should conform the Commonwealth’s treatment of net operating loss carryforwards to the 80 percent federal standard while similarly extending the carryforward provisions to pass-through businesses, as nearly every other state does.

The legislature should also consider reforming the Commonwealth’s treatment of income. It should do away with the current income class structure that does not allow losses from one type of income to offset gains from another. The current design disincentivizes small business owners who file joint returns from locating in Pennsylvania.

Lastly, Pennsylvania policymakers should conform to the federal treatment of capital investment by corporations and should consider making full expensing of capital investment permanent at the state level. Many other states already conform to this provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but it will begin to expire at the beginning of 2023. Oklahoma anticipated the change and recently became the first state in the nation to make full expensing permanent at the state level. Pennsylvania can work towards a reputation of tax competitiveness by becoming the second state to do so.

According to the state treasurer, Pennsylvania was on pace to finish Fiscal Year 2022 with a $6.6 billion surplus. However, she also noted the Keystone State could face a deficit by the end of Fiscal Year 2025. By prioritizing structural tax reforms, lawmakers made a responsible choice. Such reforms can generate recurring wage and employment benefits the likes of which a one-time relief check or new program cannot. The reforms of HB 1342 are a good start to making Pennsylvania-based corporations more competitive and to fueling productivity and wage growth in the Commonwealth. As lawmakers in Harrisburg consider how to proceed in the future, they should build on the present reforms with confidence and an eye to the successes of states that were once in their position.