Nudging Competition Authorities to Work Under the Gender Lens

In 2018, the OECD and the Canadian Competition Bureau launched the Gender Inclusive Competition Policy project, which aimed to explore the interdependence between the gender perspective and competition policy. Seven research proposals were selected based on their interesting initial findings, which provided specific examples of how competition policy might benefit from adopting a gender perspective. Although the study proposals were published and discussed during an OECD workshop in February 2021, as of this writing, there has been limited progress in further exploring these findings or promoting new initiatives concerning gender and competition policy.

To further advance the findings of the aforementioned studies, this article suggests that competition agencies need to be nudged to incorporate a gender perspective into their day-to-day activities. This approach would not only contribute to a deeper understanding of gender and competition by means of collecting more empirical data but would also help to explore other alternatives to enhance competition in markets.

The following sections will elaborate on the concept of a gender perspective and the reasons for incorporating it in competition policy. Furthermore, specific examples will be provided on how the concept of nudging, drawing from behavioural economics, can be applied within competition agencies to encourage gender consideration in their daily tasks.

What is the gender perspective and why should competition policy care about implementing it?

Following the UN criterion, the concept of gender refers to both men and women. Therefore, when the term gender perspective is used, it must be understood precisely as considering the different genders that exist and the manner in which either one of them has been relegated by laws and policies.

The legal literature has pointed out that law and its institutions have been historically designed and shaped by men (MacKinnon, Toward a feminist theory of the State, 1991) and consequently, implicit assumptions can be found in existing laws that contribute to the absence of a gender perspective (Levit, The Gender Line, 1998). For this reason, the perspective of other gender groups –such as women– has not necessarily been incorporated into the legal mix and competition law is no exception to this situation.

This absence of a gender perspective in the law and its institutions is compounded by contingencies that tend to affect women in particular. As a relatively recent example, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the last report of the World Economic Forum set out that the years needed to achieve full parity increased from 100 to 132 years, assuming that the rate of progress would remain the same throughout that period. Last March, the UN Commission on Status of Women emphasized how crucial it is to continue tackling the gender gap despite other pressing issues.

Beyond reasons linked to the gender parity goal, women as a gender group put forward compelling arguments to be considered in competition policy in terms of economics. According to the latest data available from the World Bank, women made up 39,7% of the world’s workforce in 2021, had a life expectancy of 75 years in 2020 (as opposed to men’s life expectancy of 70 years) and constituted 49,7% of the world’s population in 2021. These numbers are significant in terms of competition and markets, especially if we consider that the consumption patterns of men and women may differ depending on the market under analysis, especially in ‘sensitive’ markets, such as labour, transport or household items. In any competition investigation, whether of anti-competitive conduct or merger control, the authorities need to obtain as much information as possible to conduct a sound analysis of the market under analysis. How can this analysis be comprehensive if it does not examine a priori the possibility of a difference in consumption behaviour according to gender? This issue is compounded by the gap in data collection between men and women (Criado Perez, Invisible Women, 2019), a fact confirmed recently by the UN.

In this regard, authors such as Santacreu-Vasut and Pike suggest that incorporating the gender perspective may reduce market distortions and, at the same time, it could help in reducing gender inequality. To mention a few examples from the legal literature, Santacreu-Vasut and Pike observed that women are less involved in the participation of cartels, which according to Haucap and Heldman could indicate an under-representation of women in leading positions in companies or a lower propensity to collude.

Indeed, it seems reasonable to suggest that the object of competition policy –often to as consumer welfare– may not be achieved if the competitive analysis is biased, for instance, by not considering the perspective and outcomes of particular groups of people that seek to protect – such as women. As noted by Long, consumer welfare is not maximised if it is subject to inequality. According to the author, if markets are influenced by gender bias, or if the structure and functioning of the markets aggravate gender inequality, this translates into an impact on consumer welfare, which is the cue for competition authorities to intervene.

Thus, including the gender perspective in competition policy and law entails considering men and women in a cross-cutting manner (in addition to other categories that society constructs as it develops) in market analyses, which are at the core of competition assessments. This approach can contribute to reducing distortions in markets and promoting consumer welfare, as it acknowledges the impact of gender on market dynamics. Recognising and addressing gender biases in competition policy can result in more inclusive markets that benefit all consumers.

How can we nudge competition authorities to start working bearing in mind the gender perspective?

Having raised the need to consider the gender perspective in competition policy, the next question is, logically, how should it be incorporated. Regarding the research proposals of the OECD and the Canadian Competition Bureau’s Gender Inclusive Competition Policy project mentioned before, it is worth noting that the majority of the proposals revolve around the adoption of tools and strategies by competition agencies during the investigation and enforcement stages, while only one of the seven proposals involves a legal amendment. Indeed, using South Africa as a reference, the work of Mkatshwa, Tshabalala and Phala proposes incorporating gender perspective as a part of the public interest values associated with equity that are already included in South African competition law, especially regarding concerning merger regulation and the adoption of measures to prioritise historically disadvantage groups. The authors advocate for the inclusion of non-economic goals in competition policy and state in their conclusions that all societies should incorporate such considerations.

In fact, in recent years there has been a growing tendency to discuss the feasibility of incorporating non-economic goals into competition policy. Last December, the OECD’s Global Forum on Competition discussed whether competition law could be adapted as a policy instrument to address new socio-economic trends better. The academic community has particularly referred to the relationship that competition law could have with sustainability and economic inequality, respectively. In this context, gender equality advocates may see this as an appropriate instance to set this interest in the goals of competition regulation.

Yet, changing regulations in any country usually faces a lot of resistance and, major progress in the right direction may not be seen for years. In addition, the approach taken by the remaining six studies suggests that practical measures that integrate gender perspective should be easier to incorporate into the daily practice of competition authorities. Indeed, more immediate solutions are needed in order to address the absence of a gender perspective in the analysis of competition agencies. This is where the concept of nudge coined by Thaler and Sunstein (Nudge, 2021) can be a source of inspiration. One of the core elements of nudging someone consists of an intervention that can be easily avoided without significant costs. In that sense, a nudge is not an obligation, but a suggestion. Thaler and Sunstein argue that the benefit of nudging is to improve people’s lives without altering their freedom to make decisions. The authors presented an example where a school aimed to influence students’ food choices towards fruits and vegetables by displaying them at eye level in the cafeteria while placing other food options –like fries or candies– in lower sections of the shelf. After a few weeks, the students started to incorporate more fruits and vegetables into their diets. The intention was to make healthier food choices visible and accessible, without completely removing other options from students.

Applying this concept to tackle the lack of a gender perspective in competition law –by putting this perspective at the agencies´ “eye level”– could lead to two possible outcomes: either they will be influenced to start working by considering the gender lens or not. Ultimately it will be up to the agencies to decide whether to adopt these suggestions. Certainly, all of this is merely a theoretical exercise that, if proven to be effective, could lead to the positive results described in the previous section. Nudges must not only be attractive on their own but must also come from convincing entities with the ability to trigger the intended change. The following three sections address the proposed instruments to incorporate the gender perspective in competition policy.

The influence of academia and international organisations

It would be helpful that the academic community and international organisations to refer to the interrelationship between gender perspective and competition policy as one of the priorities in their agendas. Discussing competition policy and implementing new goals –such as gender perspective– requires the participation of experts from the academic community, research centres, and international organisations such as the OECD, as well as associations and forums linked to competition law. Further research and analysis of the interdependence between gender and competition are essential to engage in the search for solutions that promote greater market competitiveness. It is up to these experts and organisations to advocate for the inclusion of a gender perspective in the competitive assessment of markets.

The gender lens in defining relevant markets

There is no need to go far to find interesting and easy-to-implement proposals. The example of Canada comes in handy: Canadian public authorities promote the inclusion and use of a “Gender-based Analysis Plus” tool, which consists of incorporating questions into the daily duties of public employees to recognise gender specificities, when appropriate. These questions work as a checklist where the public servant has to discern whether there are gender biases on his or her part that could influence the decisions they take on a daily basis.

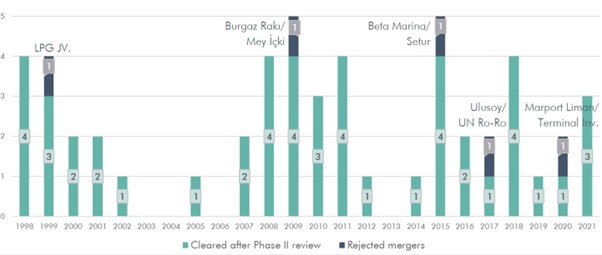

Translating the tool into antitrust, market definition presents a natural opportunity to incorporate the gender opportunity due to its adaptable and instrumental nature, particularly in Market studies must collect all the information necessary for their analysis, so the inclusion of gender-related data is an additional input for the authorities’ task to identify competition problems in markets, resulting in an absolute gain according to Santacreu-Vasut and Pike. Meanwhile, incorporating the gender perspective in merger control would provide additional information for the authority, especially in ‘sensitive’ markets for consumers through more tailored surveys. In addition, the regularity with which staff members in competition agencies have to define markets in the context of merger control makes adapting a checklist for gender mainstreaming a standard part of the routine and may eventually result in a relatively natural application. This proposal is easier to implement than a legal amendment, although it requires efforts on the part of competition agencies, which leads us to the next proposal.

The domino effect caused by competition authorities: a wink at the Brussels effect

One nudge that has proven effective in other circumstances is the leading competition authorities’ influence on other competition agencies. It is not a coincidence that the influence of the European Commission on other jurisdictions has been recognised as the Brussels Effect. Getting such influential competition authorities as the European Commission to promote working from a gender perspective may be more than enough for other agencies to follow suit.

There seems to be enough space in the current EU legislation to consider the gender perspective in competition matters. Article 2 of the TEU governs the actions of the Union’s bodies and establishes equality between women and men as one of the Union’s values. So technically, there is a binding reason to justify the adoption of a gender perspective in the EU competition agency, even though it has never been mentioned in the application of Article 101 TFEU, as pointed out by Brook. Anyhow, what is relevant is to accumulate more experiences and results from different jurisdictions that will enrich the debate on the relationship between competition law and the gender perspective and both the European Union and its member countries are ideally placed to make a valuable contribution.

Implementing these three nudges would be an important initial step to assess from an institutional approach whether the gender perspective should be part –or not– of the new objectives of competition policy. In any case, its materialisation as a goal does not imply that it should not be an inherent part of the analysis of competitiveness in the markets. After all what matters is to make markets competitive for all, since consumer welfare as an ultimate competition law goal does not –or should not– discriminate based on gender.