Nonresident Income Tax Filing Laws by State

If you filed your taxes by the April 15th deadline, you’re probably relieved to return to your daily routine without thinking too much about income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

payments, forms, and filing obligations until next year. Tax season is a dreaded time for many, in large part due to the complexity involved in filing. In a recent poll conducted by the Tax Foundation’s educational program, TaxEDU, and Public Policy Polling, 88 percent of respondents indicated they believe the U.S. tax code is either overly complex or somewhat complex. But the complexity people complain about is the complexity people know about. Plenty of tax complexity exists that most Americans aren’t even aware of. Among the tax rules Americans understand the least—and also comply with the least—are nonresident income tax filing laws.

Very few Americans realize that nearly half the states technically require individuals to file nonresident individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S.

returns if they work for even a single day within that state. And even if more Americans were aware of these obligations, very few would go to the effort of filing income tax returns in every single state in which they work for a day or answer some emails while on vacation. This is especially true in states where employer withholding laws are more lenient than nonresident employee filing laws, which is often the case. And since taxpayers can claim a credit for taxes paid to other states against their home state income tax liability, short-term travel has a negligible impact, if any, on a taxpayer’s total state tax liability.

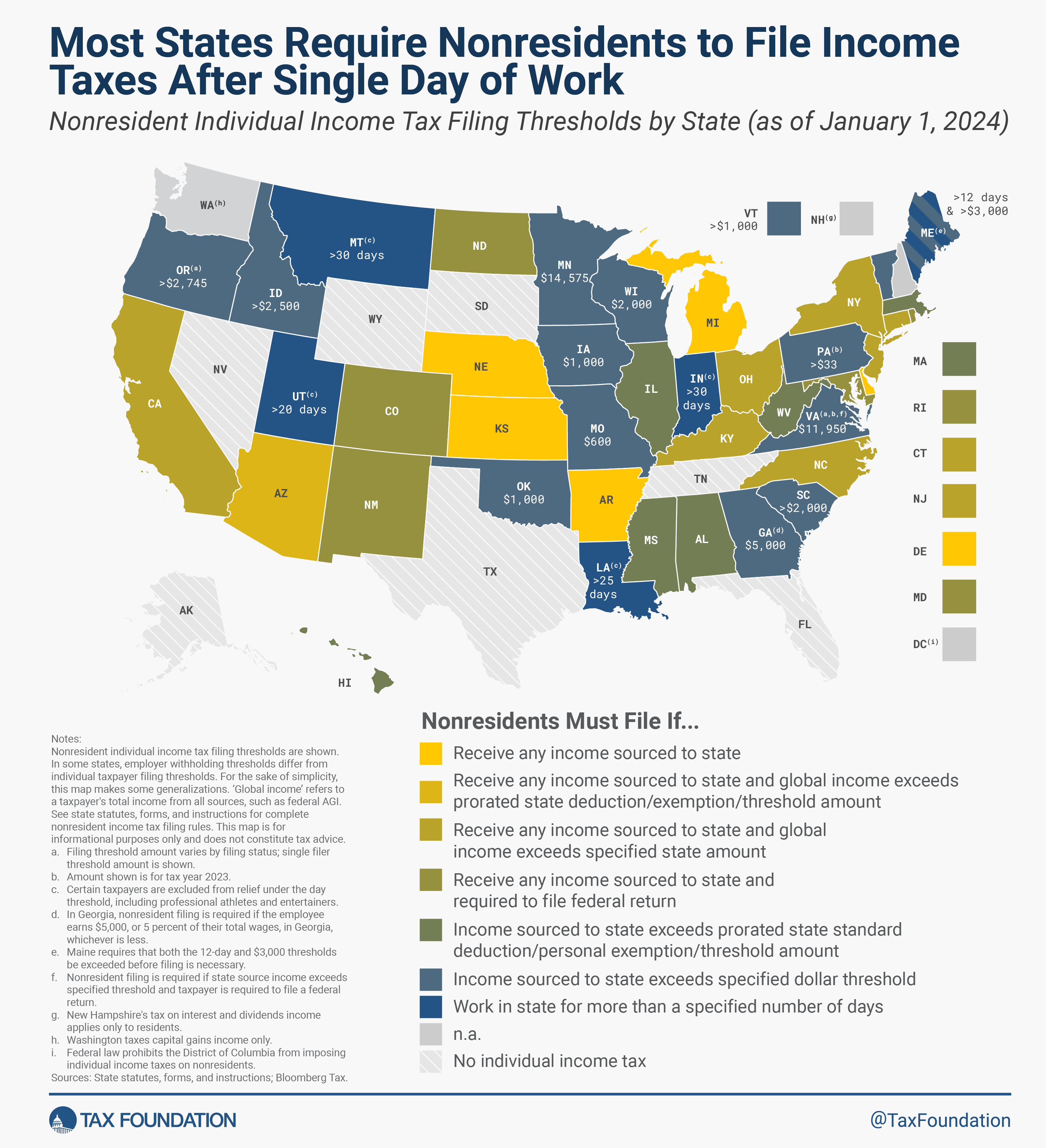

In each of the 24 states shown in yellow on the map, nonresidents are likely to incur income tax filing obligations by working just a single day in the state. Meanwhile, the states in blue have thresholds in place that protect nonresidents from having to file if they work only a short amount of time (or earn only a small amount of income) in the state.

The strictest nonresident filing obligations are found in Arkansas, Delaware, Kansas, Michigan, and Nebraska, where nonresidents are required to file a return if they earn any income in the state. Other states, like Colorado, Maryland, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Rhode Island, require nonresidents to file if they earn any income in the state and earn enough total income to be required to file a federal return. (In general, individuals are required to file a federal return if their gross income exceeds the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes.

for their filing status, which in tax year 2024 is $14,600 for single filers and $29,200 for married couples filing jointly, meaning most workers are required to file.)

Similarly, other states tie their nonresident filing obligations to whether the taxpayer’s total federal income exceeds a specified amount other than the federal standard deduction. (These state-specified amounts often differ by the taxpayer’s filing status and sometimes by their age, but in all cases, these thresholds are so low as to typically provide filing relief only to part-time workers who are less likely to travel for work anyway.)

In Alabama, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and West Virginia, nonresidents must file if their state-sourced income exceeds the state standard deduction and/or personal exemption amount, but deductions and exemptions must be prorated based on the ratio of the taxpayer’s state-sourced income to their federal income. As a result, a nonresident’s prorated standard deduction and/or personal exemption is usually so low that it will rarely negate a taxpayer’s filing obligation. Uniquely, Arizona requires nonresidents to file if they earn any income in Arizona and their total gross income exceeds the prorated state standard deduction, capturing the vast majority of nonresidents who do any work in the state.

Importantly, the states shown in blue on the map have established statutory nonresident income tax filing thresholds designed to prevent nonresidents from having to file and pay income taxes when they conduct only minimal work in the state. Eleven states have standardized income thresholds, whereby nonresidents are relieved from filing obligations if they earn less than a de minimis amount of income in the state. These states are Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Meanwhile, four states have day thresholds, whereby nonresidents are relieved of filing obligations if they work for less than a certain number of days within the state. Indiana and Montana allow nonresidents to work within the state 30 days before nonresident filing obligations are triggered, while Louisiana allows up to 25 days, and Utah allows up to 20 days. (It is worth noting that, in each of these states, certain high-income and/or high-profile individuals are not eligible for filing and payment relief, including professional athletes and professional entertainers.) Finally, one state, Maine, is unique in specifying that nonresident filing is only required after an individual has earned more than $3,000 in the state and has worked in the state for more than 12 days.

These nonresident income tax filing thresholds are a prudent way for states to reduce tax compliance burdens for those who spend only a minimal amount of time working in a state. Notably, these policies also reduce the cost to the state of processing tax returns that have low or no income tax liability associated with them.

Most of the overly stringent nonresident income tax filing laws that remain on the books today are the product of a bygone era, when most people worked from one location, and work travel was less widespread. Those days had long since passed even before the pandemic, but that is especially true now, in an era when so many people can—and do—work from anywhere with internet access. Today, these outdated state laws fit uncomfortably within a modern economy, as evidenced by utterly low levels of both compliance and enforcement. As such, the states that have not yet adopted reasonable nonresident filing thresholds should prioritize doing so.

While a de minimis income threshold is far better than nothing, the amount of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income.

earned in a state can be difficult to determine since each state has its own definitions, exclusions, and calculations for what constitutes taxable income. This can result in taxpayers being forced to spend a great deal of time and effort running calculations to determine whether they are required to file in a certain state, regardless of whether they will actually owe taxes to said state. As such, a day threshold is a simpler solution, and a 30-day threshold is reasonable and consistent with various federal proposals to standardize these thresholds across states. To the extent states are concerned about the burden on state and local resources of nonresidents passing through, it is important to keep in mind that travelers pay a plethora of state and local sales and excise taxes on hotel rooms, meals, rental cars, rideshare services, gasoline, and much more, and these taxes paid relate much more closely to state and local benefits received than taxes based on income, which yield more arbitrary tax liabilities and carry substantially higher compliance costs.

In addition to adopting higher employee filing and employer withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests.

thresholds, more states should consider adopting reciprocity agreements—especially with their neighboring states—whereby states mutually agree that taxpayers who live in one state but work in the other are obligated to file only in their state of residence.

Tax laws should be enforceable—and generally enforced. Lack of compliance and enforcement are often symptoms of a deeper problem with the nature of the policy itself. Moving forward, one relatively easy but meaningful step policymakers can take to make future tax seasons less burdensome is to modernize their state’s nonresident income tax filing, withholding, and reciprocity laws.

Note: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute tax planning advice. For tax planning advice, please consult a paid tax preparer.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

Share