NCAs trigger antitrust sanctions against Gatekeeper Compliance Solutions

With the end of the summer holidays approaching, the NCA enforcement actions were extremely active at the end July. The Italian Competition Authority (ICA, AGCM) initiated a sanctioning procedure on 18 July against Google for the submission to users a request to consent to the linking services they offer. A few days later, the Spanish Competition Authority (SCA or CNMC) announced it is investigating Apple for conduct relating to its imposition of unfair commercial terms on developers who use the App Store to distribute applications to users of Apple products.

Both these conducts tremendously resonate with the terms in which gatekeepers submitted their compliance solutions abiding by the DMA. They may be more concerned than they should be. The DMA aims to promote contestability and ensure fairness in the digital industry. It is also based on the harmonisation basis of Article 114 TFEU. The regulation gives the European Commission the primary role in enforcing the regulations and the NCAs a secondary one. In parallel, Article 1(6) declares that the DMA is applicable without prejudice to Article 102 TFEU or national competition rules prohibiting any other unilateral conduct. The two sanctioning procedures follow the breadcrumbs secured by Article 1(6). The two sanctioning procedures: unfair is now the new black.

Unfairness can be a difficult concept to grasp. It can mean different things to different enforcers or fields of law. In the DMA, under Recital 34 it is said that unfairness means that there are imbalances between rights and obligations in relationships between business users, and gatekeepers. According to the European Commission, in its recent interpretation of unfair trade conditions under Article 102 (a) TFEU the pursuit of fairness within the DMA and Article 102 TFEU differs in terms of goals (paragraph 551 of the case AT.40437

). The EC believes that unfair conditions imposed by a dominant enterprise should be classified as unfair. This finding is supported in paragraph 552. For example, anti-steering under Article 5(4) is prohibited due to its unfair nature. Thus, unfairness in the DMA purports unfairness under Article 102 TFEU, although the EC establishes that unfair conditions are those that “are not necessary or proportionate for the attainment of a legitimate objective (…) without having to show that they have an unacceptable impact” (para 553).

Building further on this dichotomy, in the area of consumer protection, unfair commercial practices manifest in two different ways: i) if they are contrary to the requirements of professional diligence and materially distort or are likely to materially distort the economic behaviour with regard to the product of the average consumer whom it reaches or to whom it is addressed; or ii) if they fall within the category of misleading or aggressive in the sense of Articles 6 to 9 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Articles 5(2) and 5(4) of the UCPD). In the context GDPR

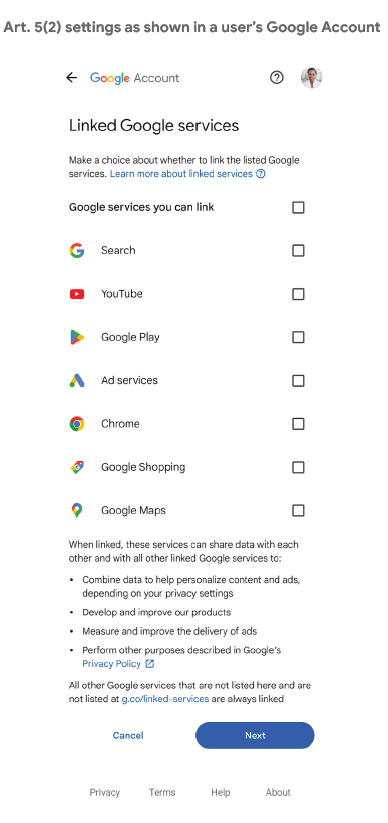

however, the principle is measured against the yardsticks of reasonable expectations and the limitation to not impose unjustified adverse impacts on the data subjects. The Italian competition authority is concerned about the consumer protection angle. The Italian NCA, which is also mandated to protect consumers by its institutional design will examine whether Google’s prompt for consenting to the ‘linking of processing’ of personal data that it collects is aggressive or misleading. The press release explains that the prompt “is accompanied by inadequate, inaccurate and misleading information, and could influence the decision of whether or to what extent consent is given”. The ICA has highlighted that the prompt does not provide any relevant information about the impact consent will have on Google’s usage of personal data. The Spanish competition authority will investigate if Apple imposed unfair terms and conditions on its developers who operate at the App Store. The ICA’s sanctioning procedure is focused on Google’s request for consent to link its services. The press release is interpreted as scrutinising Google’s compliance solution, which was introduced in response to the regulatory requirement under Article 5(2) DMA. The prompt that the ICA refers to is the one that Google included a screen shot of in its compliance document, as shown below:Image taken from Alphabet’s compliance report.

It is not contested that the New Business Terms -that the European Commission is already analysing under its third non-compliance procedure as provided by the DMA – infringe Article 102 TFEU. The European Commission has already begun to examine whether the New Business Terms, which are part of its third non-compliance process, as set out by the DMA, violate Article 102 TFEU. In fact, the Court of Justice’s interpretation of the principle of double-jeopardy in its recent bpost rules (Case C-111/20), and Nordzucker rules (C-151/20

), gives the NCAs more latitude to apply Article 102 TFEU. The DMA is very clear about its complementarity in relation to EU competition law.

As a result, public authorities can seek complementary legal responses through different procedures that form a coherent whole for addressing the different problems. (para 49, Bpost). The Court of Justice only limits the parallel sets of enforcement if i) there is a clear and precise rule that allows for the prediction of which acts or omissions will be subject to duplication of procedures and predict that there will be coordination between two competent authorities, ii), the two sets of proceedings are conducted in a coordinated manner within an immediate timeframe, and iii), the overall penalties are proportionate to the seriousness of offences committed. Articles 37 and38 DMA, in principle, enshrine mechanisms that NCAs should follow to ensure that both paths of enforcement are sufficiently coordinated. It does not mean that the NCAs’ enforcement actions are completely different in terms the legal reasoning behind them. Despite the stark differences in the manifestations of fairness, it may well be the case that the same legal reasoning underlies each of them to produce different legal consequences for the undertakings.

Even if it might sound counter-intuitive, nothing would stop NCAs from doing so. There is still a lot of room for confusion in terms of legal concepts and fields once the DMA is adopted. The AGCM’s sanctioning procedure overlaps with Article 5.2.1 DMA. The DMA prohibits the combination, processing and cross-use personal data between core platform services (CPSs), and in some cases with data from gatekeeper proprietary services or third-party services. The EC initiated a DMA non-compliance process against Meta a few days after its initial compliance deadline of March 2024. This was due to Meta’s implementation of Article 5(2) DMA. The EC’s preliminary conclusions

established that Meta’s payment model did not comply with the Article 5(2) requirements because it, among other things, “does not allow users to freely consent to combining their personal data”. The EC believes that introducing a monetisation system based on data-processing does not meet the DMA’s legal standard. In parallel to the EC’s preliminary findings, the EDPB also issued its Opinion 08/2024 on Valid Consent in the Context of Consent or Pay Models Implemented by Large Online Platforms

declaring that subscription models similar to those proposed by Meta do not abide by the terms of the GDPR.Google’s compliance solution stands in stark contrast to Meta’s: it does not introduce a fundamental shift to the monetisation of its business model, but it does propose a radical transformation to Alphabet’s data flows. The ICA’s concern is not with the data infrastructure that Alphabet has introduced, but how it presents these choices to users. Ironically, one could argue that the DMA already addresses this issue via its anticircumvention clause. The DMA’s article 13(6) states that gatekeepers are not allowed to subvert the autonomy, decision-making or freedom of choice of end users by altering the design, functionality or operation of the user interface. The overlap between the Spanish competition authority and Article 6(4) DMA

Article 6, paragraph 4, requires operating systems to facilitate alternative channels of distribution for apps and app shops. Apple’s iOS ecosystem has the most concerns about the provision’s implementation. Apple responded to this request by proposing a set New Business Terms, which its developers could choose to accept if they wished to take advantage of the DMA’s provisions. Apple’s compliance strategy has remained largely unchanged, even though it has reworked its 30% fee on all digital transactions. The truth is that most app developers are not opting into the New Business Terms, and therefore do not benefit from the business opportunities provided by the DMA. The Spanish competition authority wants to capture this exact conduct: the business conditions that developers use when they distribute their services through the App Store. Implicitly, if a developer does not wish to distribute via alternative means as opposed to the App Store, it has no need to opt into the New Business Terms.

Despite the fact that these ‘original’ terms have remained untouched, that does not make them less capturable by the DMA. Apple’s DMA plan does not include these terms, but the regulation does. The DMA cannot be applied selectively to certain business users. The European Commission has already made this point twice in two non-compliance proceedings against Apple, for its failure to comply with Articles 6(4) and 5(4) DMA. In both cases, EC revealed the obscured original’ terms which still apply to most of Apple’s corporate users. In these procedures, the European Commission will evaluate whether this false dichotomy complies with the mandate of compliance-by-default introduced by the DMA.

In the context, it is confusing that the Spanish Competition Authority will capture exactly those same terms in order to determine if they are unfair under Article 102 TFEU or the national equivalent (no doubt applying the DMA’s description). The overlap could lead to up to three different scenarios. First, neither EC nor CNMC has declared that Apple’s original conditions violate any of these standards. This seems to me the least likely outcome. Second, the EC declares Apple’s original’ business terms as a potential solution to comply with the DMA must be adapted or scraped out because they do not meet the threshold for effective enforcement. This is the most probable outcome, since it’s quite clear that Apple’s ‘original’ terms of business do not comply with Article 6(4) DMA. Apple’s false dichotomy has been designed to delay compliance by using these terms. The CNMC may also find that these business terms violate Article 102 TFEU because they are disproportionate and unjustified, such as the fee charged to developers. Or, thirdly, the Spanish competition authority might not find any evidence to add something new to the EC’s sanction under the DMA. Wouldn’t this be a resource-intensive expenditure that could have easily been absorbed by EC as the only enforcer of the regulations?

–

Three seems like too many?

The NCA contributions to the discussion surrounding the gatekeeper’s solutions for compliance advocate further the case of duplication of actions across different fields of the law regarding the exact same conduct. It is possible that they will uncover parts of the conduct which are illegal in a different way than the DMA. Parallel to this, however, the motion could put a stop on the EC’s enforcement powers, particularly when interpreting anti-circumvention in a coherent and legal manner.