Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2023) | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

Minerva and Hologic, competitors selling devices used for ablating uterine endometrial tissue, are notable for their dispute last year that gave the Supreme Court an opportunity to reassess an established patent law doctrine, assignor estoppel (reminiscent of the Court’s review of the Federal Circuit’s standard for obviousness in KSR Int’l v. Teleflex). As with KSR and obviousness, the Court’s decision on assignor estoppel did not do significant violence to the doctrine, but made it less certain and more difficult for courts to apply it consistently.

But Hologic and Minerva are, after all, competitors, and while they had a role to play in influencing patent law, their interests are properly their private businesses and fortunes, and in addition to the earlier case they were also embroiled in patent litigation over a different patent, U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208. Minerva had no more luck with that case, however, the District Court deciding on summary judgment that the patent was invalid for having been used in public more than a year before its earliest priority date (under the “public use” bar in pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)). Yesterday, the Federal Circuit affirmed the District Court judgment in a decision captioned Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc. & Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC.

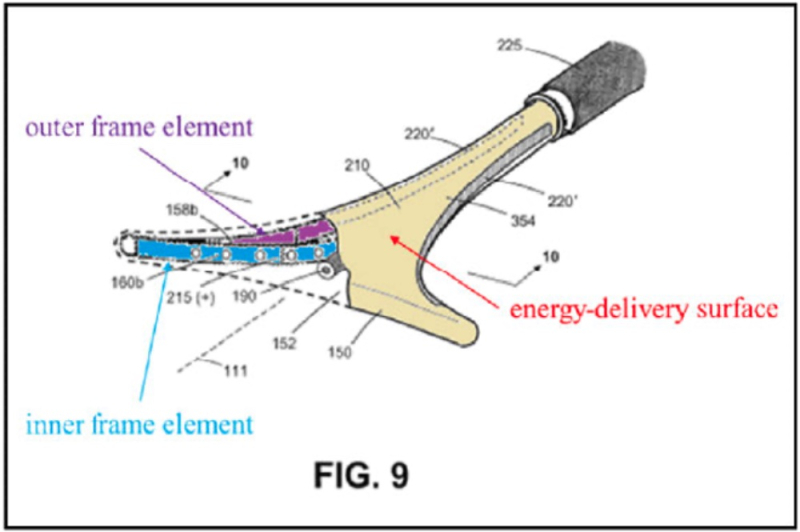

The claimed device was illustrated in the opinion by Figure 9 in the patent:

and the claims represented by Claim 13:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

(where the underlined terms were the subject of the Court’s analysis of invalidity).

The District Court’s decision on summary judgment was based on Minerva’s behavior satisfying the prongs of the test enunciated by the Supreme Court in Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 67–68 (1998), that the invention was in public use by being disclosed to the public without any restrictions or confidentiality provisions more than one year from its earliest priority date, and that the invention was “ready for patenting” (i.e., what was disclosed was the claimed invention) when it was disclosed. With regard to the latter prong, the device had “”the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (abbreviated in the opinion as the “SDMP” term) which the District Court construed as meaning that the “inner and outer frame elements have different thickness and different composition.” The facts establishing the public disclosure prong recited Minerva’s participation in a trade show — the 38th Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists and held November 16-19, 2009 (abbreviated in the opinion as “AAGL 2009”) and testimony by one of the inventors that after some failures by the time of AAGL 2009 the device disclosed at the trade show were nearly “perfect.” Minerva had a booth at the show and several (15) “fully functional” devices that were extensively demonstrated on ex vivo uteri to an audience of doctors and industry participants, a presentation by the Chairman of Minerva’s Medical Advisory Board, and an “Investigator’s Brochure” that “provided a detailed description of the Aurora device and identified that its frame elements were made of ‘Stainless steel (420 and 17-4)'” (consistent with CAD drawings prepared during development by Minerva and that the District Court found disclosed the SDMP feature recited in the claims).

Based on these facts, the District Court found no disputed material facts and granted Hologic’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity.

In the Federal Circuit’s opinion by Judge Reyna, joined by Judges Prost and Stoll, the Court agreed with the District Court that Hologic had established evidence satisfying the requirements for invalidating public use more than a year before Minerva’s earliest priority date. Relying on Delano Farms Co. v. California Table Grape Comm’n, 778 F.3d 1243, 1247 (Fed. Cir. 2015), and Dey, L.P. v. Sunovion Pharms., Inc., 715 F.3d 1351, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the panel asserted that the standard was the invention was “accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the inventor, “shown to or used by an individual other than the inventor under no limitation, restriction, or obligation of confidentiality” under Am. Seating Co. v. USSC Grp., Inc., 514 F.3d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2008). As to the “ready for patenting” prong, the Court cited Hamilton Beach Brands, Inc. v. Sunbeam Prods., Inc., 726 F.3d 1370, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2013), for the persuasiveness of there being drawings and working prototypes of the claimed invention at the time of the disclosure.

The Court rejected Minerva’s three assertions of error: that the disclosure at AAGL 2009 was not a public disclosure; that the disclosure of the device did not have the claimed SMDP feature; and that the invention was not ready for patenting because Minerva was still improving the invention at the time of AAGL 2009. As for the nature of the disclosure, the panel found dispositive that the “nature of and public access to activities involving” the disclosure were consistent with a public use because the audience consisted of “attendees who were critical to Minerva’s budding business—such as potential investors and physicians—and Minerva had every incentive to showcase the Aurora devices to these attendees as best as it could.” The extensiveness of the disclosure also supported a determination of public use, disclosing the operation of fifteen functional devices at Minerva’s booth over several days of the trade show, as well as “meetings with interested parties” and a technical presentation. This was more than “mere display,” according to the Federal Circuit in contrast to Motionless Keyboard Co. v. Microsoft Corp., 486 F.3d 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2007) cited by Minerva. The panel rejected Minerva’s contention that the disclosure was insufficient because observers were not permitted to “closely observe[] or physically handle[]” them, stating that “public use may also occur where, as here, the inventor used the device such that at least one member of the public without any secrecy obligations understood the invention,” citing Netscape Commc’ns Corp. v. Konrad, 295 F.3d 1315, 1319–21 (Fed. Cir. 2002). Summarizing, the opinion states that “[t]he inescapable conclusion of the detailed feedback Minerva received on the Aurora device is that Minerva allowed knowledgeable individuals to scrutinize the invention enough to recognize and understand the SDMP technology Minerva later sought to patent.”

In addition, the opinion cites in support of the activities at AAGL 2009 constituting a public disclosure that on the record at the District Court “there were no ‘confidentiality obligations imposed upon’ those who observed the . . . device,” nor did Minerva assert that the trade show had in place the “type of informal confidentiality obligations we have recognized in prior cases” to constitute sufficient confidentiality to rebut the existence of public disclosure, citing Bernhardt, L.L.C. v. Collezione Europa USA, Inc., 386 F.3d 1371, 1380–81 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

Finally on the disclosure prong, the Court found no genuine issue regarding disclosure of devices having the claimed SMDP feature, which was conceived prior to AAGL 2009 and regarding which there was evidence that the devices that were displayed had this feature (based inter alia on evidence that Minerva brought “fully functional” devices to the trade show).

With regard to the “ready for patenting” prong, the Court considered the record to show that the devices disclosed were “working prototypes” supported by inventor testimony explaining their function and incorporation of the SMDP feature and how they were used (i.e. with extirpated uteri). To Minerva’s argument that what it did not demonstrate was ablations on “live humans” the opinion counters (somewhat weakly) that “nothing in the intrinsic record indicating that the ‘208 patent is limited to devices only usable on live human tissue” (what else would be the device’s “intended purpose”?) despite additional “fine tuning” and “later refinements” which did not rebut reduction to practice under Hamilton Beach and Atlanta Attachment Co. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 516 F.3d 1361, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Similarly unavailing was Minerva’s contention that the device was not ready for patenting because it was not FDA approved. And the opinion states that, regardless of these considerations the disclosed devices were ready for patenting because the evidence of “drawings and detailed descriptions” in the inventors’ notebooks were “more than enough to enable a person of skill in the art to practice the claimed invention” under the Court’s Hamilton Beech precedent.

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2023)

Panel: Circuit Judges Prost, Reyna, and Stoll

Opinion by Circuit Judge Reyna