Merger Control Metamorphosis: Illumina-ting EU Merger Control

As Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke noted, just as duck hunters must anticipate the future position of their prey, antitrust policymakers are urged to foresee potential anti-competitive behaviours rather than solely focusing on past constraints.

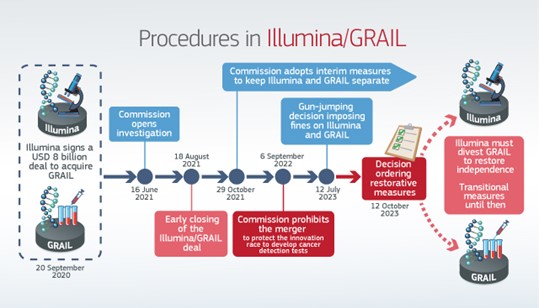

This concept of anticipating potential anti-competitive behaviours has now firmly landed on the desks of policymakers, and the last two years have proven to be legally innovative in the realm of EU merger control, with one of the most recent highlights being the European Commission’s decision for Illumina to unwind its previously finalized acquisition of GRAIL.

In this blog post, I will delve into the Illumina/Grail decision and its background, explore its significance for EU merger control, and provide guidance for practitioners, companies, and interested parties.

A closer look at the background of the decision

The case revolves around Illumina, a leading globally active genomics company whose business rests mainly on the development, manufacturing, and commercialization of the next generation of sequencing systems (NGS), purchasing GRAIL, a healthcare company developing blood-based cancer tests based on NGS.

The acquisition in question did not meet the EU notification threshold set out in the EU Merger Regulation (EUMR) nor was notified in any of the Member States. However, Illumina/Grail was the first case that the Commission accepted to review under the new Guidance on Referral Mechanism, following its referral by six of the Member States. After the Commission’s in-depth investigation, in September 2022 the Commission prohibited the acquisition of GRAIL by Illumina over concerns that it would have significant anti-competitive effects. These concerns included Illumina’s ability and incentives to foreclose GRAIL’s rivals, stifle innovation, and limit choices in the emerging market for blood-based early cancer detection tests.

While the Commission’s review was still ongoing, Illumina closed its acquisition of Grail on August 18, 2021. This action was not driven by confidence in the outcome of the litigation but rather by the “Regulatory Termination Fee” stipulated in the takeover agreement. However, this development did not yield favourable results, as the European Commission fined Illumina approximately €432 million (the largest-ever gun-jumping fine) or intentionally violating the standstill obligation and failing to adhere to the gun-jumping prohibition.

In contrast, GRAIL received only a symbolic fine of €1000, making it the first target company to be fined for gun-jumping, insofar as it played an active role in the infringement.

Decision regarding the reversal of the acquisition

After the acquisition had been declared incompatible with the internal market, in accordance with Article 8(4)(a) of the EUMR, the Commission pursued the subsequent viable course of action, which involved taking restorative measures to revert the situation that existed prior to the implementation of the concentration. Thus, on October 12 2023, the Commission adopted (i) divestment measures compelling Illumina to unwind the transaction with GRAIL and (ii) transitional measures that Illumina and GRAIL should comply with until Illumina had dissolved the transaction (find the previous summary here).

In terms of the divestment measures that were ordered, the Commission established that the transaction should aim for GRAIL’s independence from Illumina, ensuring its continued viability and competitiveness. The divestment must also be executable within clearly defined deadlines with sufficient certainty. Therefore, Illumina is required to submit a divestment plan which needs to be approved by the Commission. These measures are intended to enable GRAIL to continue the innovation race it had previously endeavoured and to prevent any anti-competitive disadvantage that Illumina might have been inclined to impose on GRAIL’s rivals.

The new transitional measures which will replace the prior interim measures adopted by the Commission foresee Illumina and GRAIL to remain separate to avoid further integration. Illumina is also obliged to maintain GRAIL’s viability by providing ongoing funding to support the development and introduction of its early cancer detection tests.

Source: European Commission Press Release: ‘The Commission instructs Illumina to reverse its finalized acquisition of GRAIL, 12 October 2023.

Why is it groundbreaking?

Over the years, a prominent and widely debated topic within EU merger control has been the possible regulatory gap existing concerning “killer acquisitions”. Although divergent opinions exist, this term refers to recent empirical and theoretical research in Big Tech and pharma industries which identified a trend for large incumbent firms to acquire start-ups with the sole purpose of eliminating potential competition. In response to these concerns, various steps were taken to adopt a more strict approach to merger control, including the new Guidance on Referral Mechanism, and the Digital Markets Act (DMA). The Illumina/GRAIL decision also serves as an illustrative example of the European Commission’s evolving rigorous stance on enforcement. This evolving approach is further evident in the recent referrals Autotalks/Qualcomm and Nasdaq Power/EEX.

The Commission’s decision to review the concentration was premised on the re-interpretation of Article 22 EUMR, which was swiftly appealed to the General Court. The General Court upheld the decision of the Commission accepting the referral request and, thereby, acknowledged the Commission’s competence to examine the concentration even if the transaction in question did not meet the turnover thresholds set at the European or national level. This acknowledgement stemmed from a thorough analysis of Article 22 EUMR, encompassing its literal, historical, contextual, and teleological interpretations. In particular, the General Court considered the referral mechanism under Article 22 EUMR as a “corrective mechanism” which provides flexibility in the turnover threshold-based system. However, Illumina’s appeal is currently pending before the Court of Justice.

Historically, Article 22 of the EUMR, also known as the Dutch clause, was in place to help some of the Member States that had no effective merger control system. Accordingly, Lord Brittan, the then Commissioner for Competition, stated during the proposal of the original ECMR: “This provision is therefore narrowly defined and would not permit the [Commission] to deal with mergers below the threshold on a general basis even if it were inclined to evade the spirit of the threshold provision in this way.”[1]. However, Article 22 currently enables the Member States to refer the acquisition to the Commission which can threaten to significantly affect competition and the trade between the Member States, even if it does not meet the national or the EU notification thresholds. The so-called Dutch clause is now used as a generally applicable corrective mechanism for the non-flexible turnover threshold mechanism.

With regards to the digital sector, with the introduction of the DMA’s Article 14, gatekeepers are now obliged to notify the Commission about all intended transactions, signalling a more strict approach to competition oversight. Under this new framework, the Commission, upon receiving these notifications, is required to share the information with the Member States to enable them to make a merger referral under Article 22 EUMR. In essence, the combined effect of the DMA’s Article 14 and Article 22 of the EUMR empowers both the Commission and the Member States to better identify the problematic transactions that may arise in the digital sector, without the inherent limitations of the thresholds-driven approach (see the views on this same point here and here).

To summarise, the Commission’s and the General Court’s interpretation of Article 22 allows any transaction to be called in for review, regardless of its size, without any proper time limit. Given that Illumina’s appeal is currently before the Court of Justice, contesting the Commission’s authority to evaluate the transaction. If this appeal proves successful, the foundation for the divestment order would become void. Despite the potential complexity of the issue, we must await the decision.

The decision is also remarkable for several reasons. It concerns the blocking of a vertical (non-horizontal) merger. Additionally, it is the first time that the Commission has ordered the unwinding of a finalised acquisition, and it is the first time that the Commission has used the novel innovation theory of harm against a vertical merger, based on its predictions by 2035.

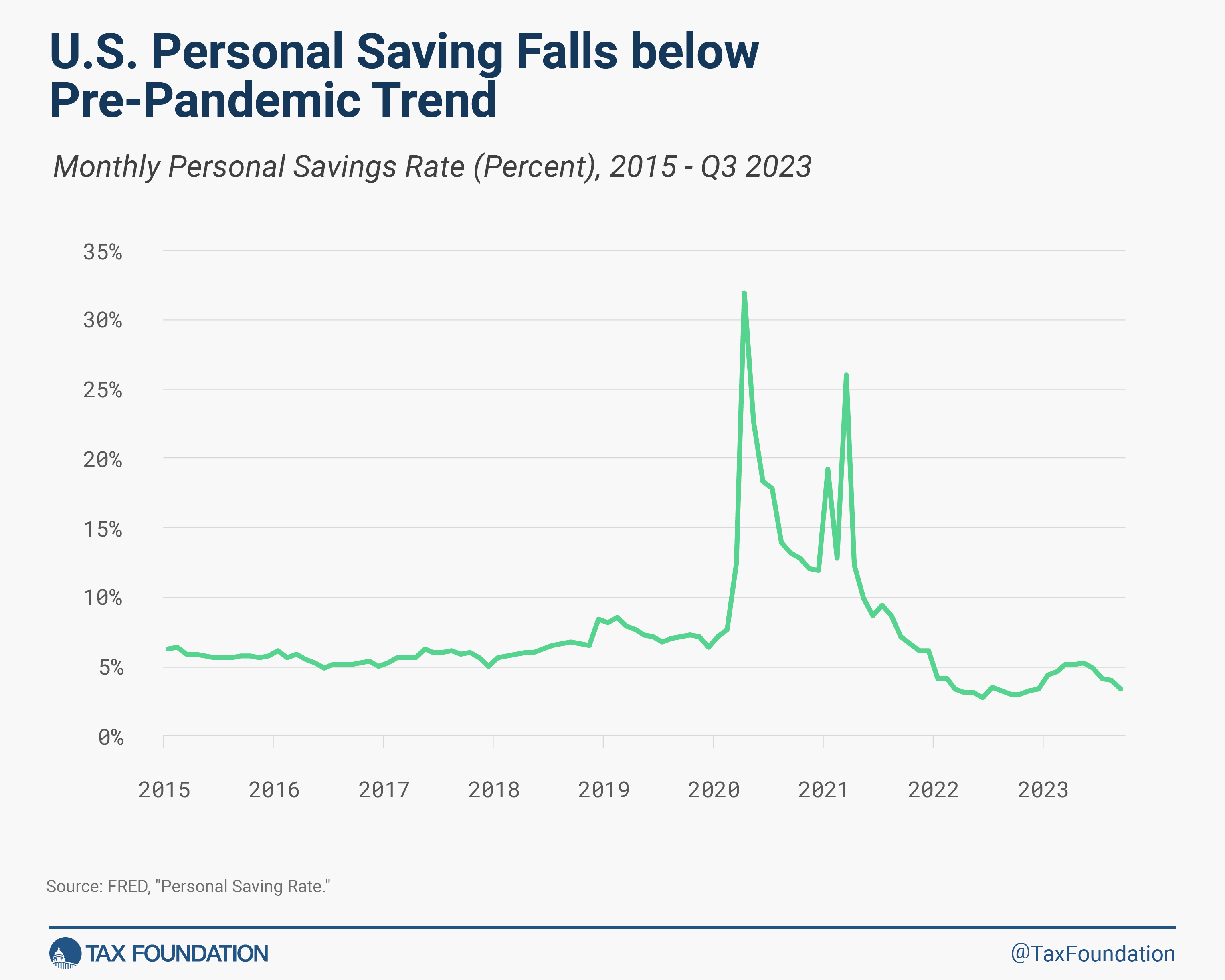

The innovation theory of harm is a concept which focuses on the potential negative effects of a transaction on innovation within an industry. Nevertheless, it can be challenging to evaluate, especially when research and development (R&D) activities do not follow a clear and well-defined process. Critics argue that the threat of future enforcement actions based on future market situations might discourage prospective merging parties from entering into efficiency-enhancing mergers. According to the Commission’s assessment, the nascent market for blood-based cancer tests will have a volume of around EUR 40 billion per annum by 2035, and this market is based on NGS technology, in which Illumina is actually the dominant player.

The Commission identified the potential of a foreclosure effect on the innovation race within the relevant market should the acquisition take place. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the connection between innovation and market structure lacks a clear consensus. Interestingly, the theory surrounding vertical mergers can suggest anti-competitive foreclosure. However, empirical evidence predominantly favours the perspective that the majority of vertical mergers have pro-competitive effects, such as the elimination of double marginalization. Thus, many commentators argued that even if a vertical merger were to harm a rival, it could still lead to lower overall prices and consumer welfare could rise. Such a transaction is pro-competitive under antitrust, and the theory that they harm innovation remains inconclusive and uncertain for practical use. However, to understand the Commission’s approach, we must wait for the release of the complete text of the decision.

In terms of the unprecedented unwinding decision, “unscrambling the eggs” could be seen as costly and complex since the transaction has already been consummated, and even after divesture, conditions might not be able to restore the level of competition that prevailed prior to the acquisition.

Practical Implications

The Illumina/GRAIL decision signals the commencement of a new chapter in the future of merger control in the EU and signifies a shift towards a more interventionist and innovation-focused approach. Pending confirmation by the Court of Justice, the recent endorsement by the General Court of the Commission’s interpretation of Article 22 empowers the Commission to assess any transaction that poses a risk to competition law, even if the transaction in question does not meet the European turnover thresholds or those at the national level. However, this policy shift may introduce significant business implications.

Companies are also suggested to make voluntary notifications for their transaction if they encounter any concerns during their due diligence process, even in cases where these transactions fall below the turnover threshold requirements. Failing to provide such notifications could result in prolonged legal uncertainty, extending beyond the transaction’s closure, as the General Cour’’s interpretation of the“”start date”” of the 15 working days is relatively broad (the deadline may not be triggered until the Member State considers that it has enough information to make an evaluation).

It is crucial to establish appropriate financial consequences in the deal documentation, considering the potential delays caused by external factors such as referral and pending approval by the European Commission. As exemplified in the Illumina/GRAIL transaction, the parties could not wait for the clearance by the Commission and incurred the largest fine ever in a gun-jumping case. Thus, parties involved in a transaction should be aware of the risks and seek legal advice to navigate the complex merger control procedures.

Concluding Remarks

As noted above, EU merger control is currently experiencing a period of significant developments, including the introduction of the new Guidance, the DMA, and a highly debated opinion from the Advocate General on the Towercast judgement confirming the application of the concept of abuse of a dominant position to mergers that are not subject to notification requirements (see my comment on the opinion here and already existing case for further details). All these developments point to a single overarching trend: a more stringent approach imposed on undertakings with fewer opportunities for its evasion.

Thus, it is important to emphasize that the Illumina/GRAIL decision also holds notable significance for merger control procedures in this rapidly changing environment. While it may not be an everyday occurrence, Illumina and GRAIL were expected to be aware of the established policy goals and the Guidance. There are valuable lessons to be drawn from the judgement such as recognising the significance of the transaction in advance and refraining from implementing and complying with the standstill obligation. While we need to wait for the release of the full text to clarify the discussed points, even at this stage, the decision is very illuminating.

________

[1] L. Brittan, ‘The development of merger control in EEC competition law’ in Competition Policy and Merger Control in the Single European Market, 1991.