Massachusetts Graduated Income Tax Amendment: Details & Analysis

Key Findings

- Massachusetts’ tax advantage in New England is primarily driven by its competitive individual income tax rate and its sales and use tax structure.

- The graduated income tax amendment would be paid by many small businesses, in addition to wealthy individuals.

- The proposed surtax is likely to have negative economic effects that will impact low- and middle-income earners.

- If approved, the graduated income tax could contract the Massachusetts economy by $6 billion by end of 2025.

- Massachusetts has seen net outmigration of adjusted gross income (AGI) since 1993, resulting in $23 billion of AGI flowing to other states.

- Florida and New Hampshire, two states with no individual income tax, are consistently the top destinations for net outmigration of AGI from Massachusetts.

- The graduated income tax amendment is likely to exacerbate the net outmigration of AGI from Massachusetts as taxpayers adjust their behaviors to the tax increase.

- Responding to potential negative economic effects of the surtax by repealing or adjusting the rate would require another constitutional amendment, which would take years to accomplish.

Introduction

This November, Massachusetts voters will decide whether the state’s constitution should be amended to transition the Commonwealth from a flat rate individual income tax to a graduated rate tax with a high top marginal rate. If approved, the amendment would impose a 4 percent surtax on income over $1 million, raising an estimated $2 billion per year in new revenue.

Proponents of the amendment have framed the issue as a response to income inequality, with the surtax advertised as only affecting the wealthiest residents of the Bay State and thus ensuring that the wealthy pay their fair share. [1] This motivation is unsurprising in a state known for its progressive politics, and the Commonwealth’s flat-rate income tax is anomalous in a tax code that otherwise bears the hallmarks of progressive taxation. Less publicized are the compelling reasons to believe the surtax may generate negative economic consequences that outweigh any social benefit from additional tax revenue. And there are hints that the Bay State’s voters care about this too, for the single rate income tax has had staying power, long favored by residents.

To bring those issues into the light, this paper will outline the current tax landscape on which the surtax would be appended and the ongoing negative migration trends the surtax could exacerbate; discuss the findings of important academic research on income tax changes; and conclude by addressing the potential long-term consequences the surtax could have on the people of Massachusetts, including on residents—the vast majority of them—who would not owe the tax themselves.

Massachusetts’ Tax Backdrop

Over the past two decades, Massachusetts has largely shed its historic moniker of Taxachusetts. This is primarily due to the reductions in its corporate and individual income tax rates. In 2000, the corporate income tax (CIT) rate was 9.5 percent and the individual income tax rate was 5.85 percent. Nearly every year since, incremental rate reductions were implemented. Today those rates are 8 percent and 5 percent, respectively. For decades, moreover, a property tax limitation regime has kept property tax collections in check, even as they have risen dramatically elsewhere in the region. Today, while no one would mistake Massachusetts for a low-tax state, it has carved out a place as a competitive area to live and work within the Northeast corridor.

This is not to say that the entirety of Massachusetts’ tax system is fixed. There are still many improvements that could be made, but consider the Commonwealth’s ranking on the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index—particularly with regard to the individual income tax.

The improvements Massachusetts made to its tax code since the 1980s in terms of corporate and individual income tax rate reductions have helped the Commonwealth become more competitive, but in 2022, the Bay State still ranked 34th overall on the Index—well below the median. Its ranking is kept down in large part by its worst-in-the-country unemployment insurance tax system and by its property tax system, which ranks 45th (due to business property taxes and estate tax burdens) despite attempts to cap residential property tax burdens. Its corporate tax rank (36) also underperforms, and despite the rate reductions, the CIT is still anchored by the 13th highest rate amongst states that levy the tax.

Massachusetts’ competitive tax advantage in New England is primarily due to its individual income and sales tax systems, which rank 11th and 12th on the Index, respectively. With regard to its neighbors, only New Hampshire has a better overall Index ranking than Massachusetts.[2] The individual income tax, in particular, is the cornerstone of Massachusetts’ tax competitiveness, reducing the cost of employment in the Commonwealth and increasing the return to labor. It helps offset high business tax costs and makes Massachusetts more attractive to high earners and entrepreneurs.

Crucially, it also helps keep taxes affordable for small businesses, most of which are pass-through entities, meaning that their owners or investors pay taxes on business earnings through the individual rather than corporate income tax. A competitive income tax rate is important for these businesses, which face high taxes in other areas, as well as a higher-than-average cost of doing business outside the tax realm. While most small businesses are very small—the median small business is not only a sole proprietorship, but typically a side gig—most of those employed by small businesses work for those on the larger side of “small,” the sort of businesses that can easily be affected by the proposed higher rate. In fact, 43 percent of all income from pass-through businesses in Massachusetts is on returns that would be subject to the surtax.

Because the proposed tax would be written into the constitution, it does not give the legislature the ability to introduce additional brackets without going back to the voters at least once more for that authority. But it does implement the idea of progressive income taxation, which voters in Massachusetts have long been wary of, perhaps recognizing that a single rate tax is the only reason why the state’s income tax rate is low, and that even low- and middle-income earners may ultimately face higher marginal rates if the Commonwealth is ultimately empowered to adopt a graduated rate tax.

The Economic Ramifications of High-Rate Income Taxes

Individuals and small businesses bringing in $1 million are not typically the recipients of a great deal of sympathy. Some people may possess a sense of fairness that opposes disproportionately high taxes on them as a matter of principle, but for most, what matters more is how it affects the broader public: what it does for the Commonwealth’s economy, understood in terms of jobs, growth, opportunity, and income-earning potential for individuals who will never join the rarified company of those actually remitting under the proposed surtax.

In 2007, Christina Romer and David Romer, professors of economics at the University of California Berkeley, conducted a study to determine the impact of legislated tax changes on the economy. Their conclusion: tax increases have a strong contractionary effect on the economy. Much of that negative effect was attributed to the significant decline in personal consumption—what consumers spend on goods and services—and the significant decline in private domestic investment—what private businesses invest in the domestic economy.[3]

The study found that a tax increase equal to 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) resulted in an estimated 3 percent decline in GDP after three years. Proponents of the surtax estimate that the Commonwealth will raise $2 billion in new annual revenue from the tax increase. That amounts to a tax increase of 0.314 percent of Massachusetts’ gross state product.[4] If the Romer and Romer study were applied to the Massachusetts surtax it would result in a 0.942 percent decline in GDP after three years. In other words, the Commonwealth’s total economic output could contract by $5.98 billion by the end of 2025 due to the surtax alone.[5]

With regard to the components of GDP, Romer and Romer found that if taxes are increased by 1 percent of GDP, personal consumption expenditures and private domestic investment consistently decline for more than two years. Just over two years after the tax increase occurred, total personal spending on goods and services was estimated to drop by 2.6 percent while personal spending on durable goods (such as home appliances, electronics, and cars) was estimated to drop by 8.6 percent. Likewise, approximately two years after the tax increase, the amount private businesses invest in the domestic economy was estimated to drop by 12.6 percent.[6]

In 2020, Massachusetts households spent $358.5 billion on goods and services.[7] Using Romer and Romer’s estimates as a guide, the 4 percent income surtax could reduce personal consumption expenditure by Massachusetts households by $2.9 billion in just over two years.[8] Practically speaking, a decline in consumption of that magnitude means the collective standard of living for all Massachusetts residents could be nearly $3 billion lower after two years as a result of the surtax.

Notably, Romer and Romer’s study was completed with U.S. federal income tax data, not state level data. This means that it likely understates the impact of the tax, because the authors assumed what economists call a closed economy, where the factors of production are constrained to remain within a country’s borders. In contrast to the national economy, subnational economies are much more open. Since it is easier to avoid the impact of a particular state policy by relocating labor or capital to a different state, it is reasonable to assume that the empirical findings of a national study could be magnified at the state level.[9]

Massachusetts is a geographically small state located in a region of geographically small states. Capital is mobile and labor is increasingly so, especially as remote work options have become viable for many more employees post-pandemic. Thus, it would be relatively easy for producers and consumers to adjust their behavior and location to avoid a new 4 percent income surtax. A small business subject to the tax, that might benefit from Massachusetts’ qualified workforce, can more easily relocate to another state, knowing that it can draw from a workforce spread out across the country. Similarly, successful entrepreneurs might decide to locate elsewhere. It is not difficult to imagine the negative economic effects identified by Romer and Romer occurring more rapidly or to a greater magnitude in Massachusetts than in the United States as a whole.

While the structure of the major taxes matters, perhaps more important is how the various taxes interact with each other. For instance, taxpayers may be more willing to live in a state with high property taxes if that means a state forgoes an individual income tax or levies a very low income tax.

Similarly, the tax system is one of many factors that people take into account when determining where to live or where to locate a business. They care about crime rates, school quality, access to infrastructure, weather, human capital, and a host of other issues. For instance, New York features undeniably high taxes, to the point that recent governors—no foes of progressive taxation—have urged caution or even endorsed significant tax reform and tax relief. But New York City is a commercial and financial hub. Many people are willing to pay high taxes for the privilege of easily accessing a city with global influence and accessibility. And yet many others are not.

Some never moved to New York in the first place and could have been drawn there if taxes were lower. But New York policymakers now recognize remote work as a particularly serious risk, because many of those previously tied to the Big Apple now have the flexibility to work elsewhere without sacrificing their jobs. Those who are willing to pay large premiums—in tax, in rent, and in other costs—to live near Broadway, dazzling museums, and stellar restaurants will remain. But what about those who were there only of necessity?

When it comes to producing goods or services, there are four factors that must generally be present: land, labor (people to do the work), capital (equipment/money), and entrepreneurship (people to organize and lead the business). Of these factors, capital is commonly understood to be the most mobile. Relatively speaking it is easier to move equipment or money to a different jurisdiction than it is to relocate a person or family to a new residence. Thus, it should not be surprising that capital is sensitive to higher rates of taxation.

At a certain point, the tax burden becomes too much for people and businesses to bear. Where that tipping point is varies by firm and individual. But when the benefits of residing within a high-tax jurisdiction no longer outweigh the costs, taxpayers seek relief in more tax-competitive jurisdictions. The relocation of General Electric from Connecticut illustrates this point.

When GE announced in 2016 that it would move its corporate headquarters from Fairfield, Connecticut to Boston, it cited the ambition of “being the most competitive company in the world.”[10] GE chose Boston in part due to the city’s 55 colleges and universities and its ability to “attract a diverse, technologically-fluent workforce.”[11] But many of those same benefits were available in Fairfield and in New York City (where it already had a presence at Rockefeller Plaza). The main issue affecting GE’s competitiveness in Connecticut was the state’s 2015 decision to legislate a $700 million tax increase on businesses.[12] According to GE’s CEO, that is what ultimately prompted the search for a “more pro-business environment.”[13]

Massachusetts is already trending in the wrong direction in terms of migration. Since 2013, Massachusetts’ net population change levels have been trending downward; and in 2020 the Commonwealth realized its first net negative population change since 2004. Massachusetts lost an estimated 1,309 residents in 2020 but that figure grew to 37,497 by 2021. Much of that change is likely attributable to various changes brought on by the pandemic, including the expansion of remote work opportunities. However, Massachusetts’ struggle with migration precedes the pandemic.

The Bay State’s net migration levels generally mirror the downward trajectory of the net population change figures, but a closer look reveals that Massachusetts was experiencing net negative migration even before the pandemic began. The downward trend for net migration reached net negative levels in 2019, the first year since 2007.

Whether Massachusetts’ net migration figure is positive or negative primarily depends on the strength of net international migration. For 20 of the last 22 years, Massachusetts has seen net negative domestic migration. What this effectively means is that it is preferable to migrate to Massachusetts from abroad, but once a person lives there, it is preferable to move somewhere else. Between July 1, 2020 and July 1, 2021, an estimated 12,675 more people moved to the Bay State from abroad than left for foreign destinations. However, 46,187 more people left Massachusetts for other domestic locations than moved in from elsewhere in the United States.[14] This should concern policymakers, but the figure that should be even more concerning is the net outmigration of adjusted gross income (AGI).

AGI is important economically because income levels drive household spending, which makes up more than two-thirds of economic activity in the United States.[15] It is important from a tax revenue perspective because that is the income subject to the individual income tax, which accounted for more than 57 percent of Massachusetts’ total own source tax revenue in Fiscal Year 2021.[16]

Notably, Massachusetts has realized a net outmigration of AGI every year since 1993. Over that time, Massachusetts’ economy has lost nearly $23 billion in AGI to other states.[17] In 2020 alone, the Commonwealth saw an estimated $2.5 billion decline in net AGI. At the 5 percent individual income tax rate, the amount of AGI lost to other states since 1993 could have generated $1.15 billion in tax revenue for the Commonwealth, to say nothing of the multiplicative effect the income could have had in future years had it circulated through the local economy.

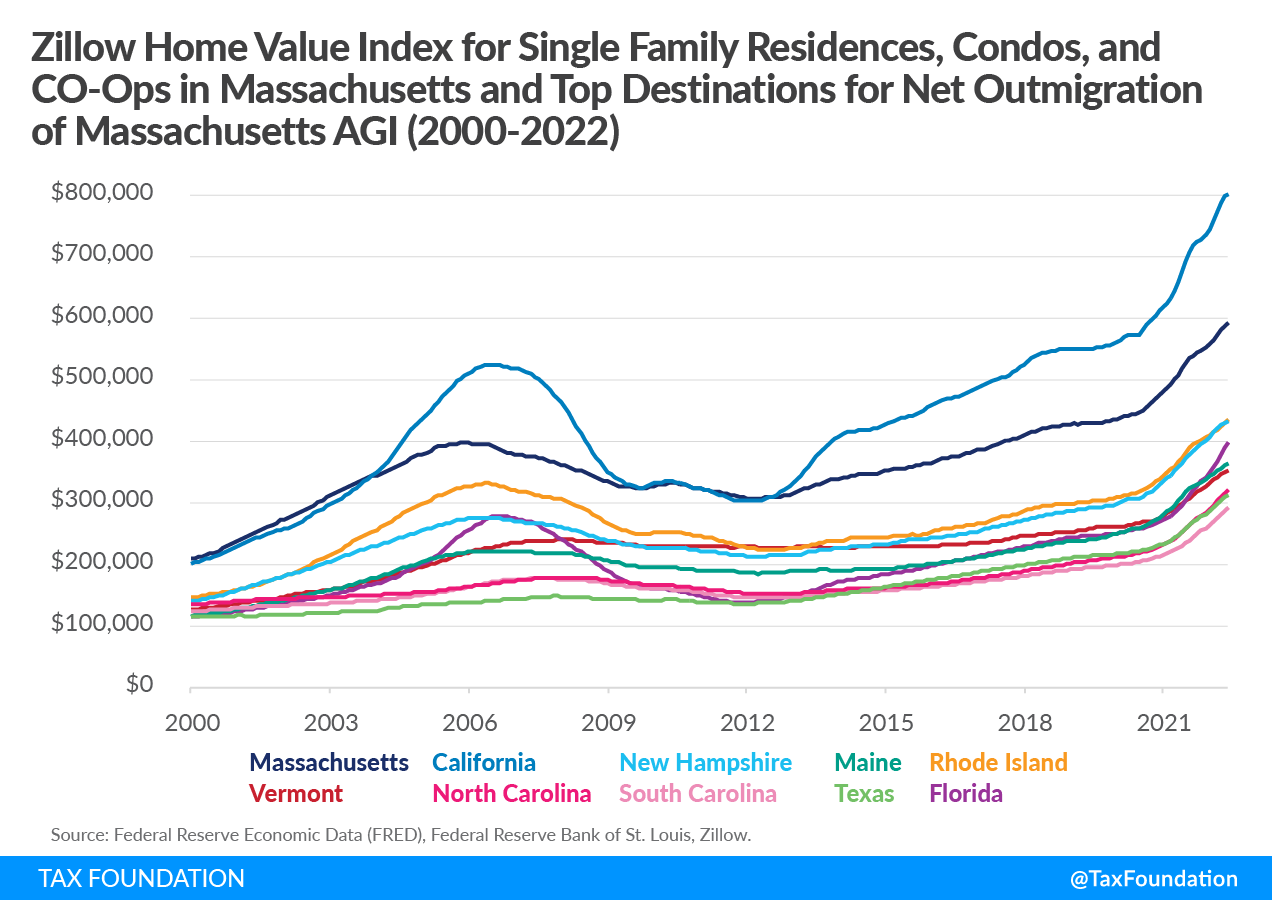

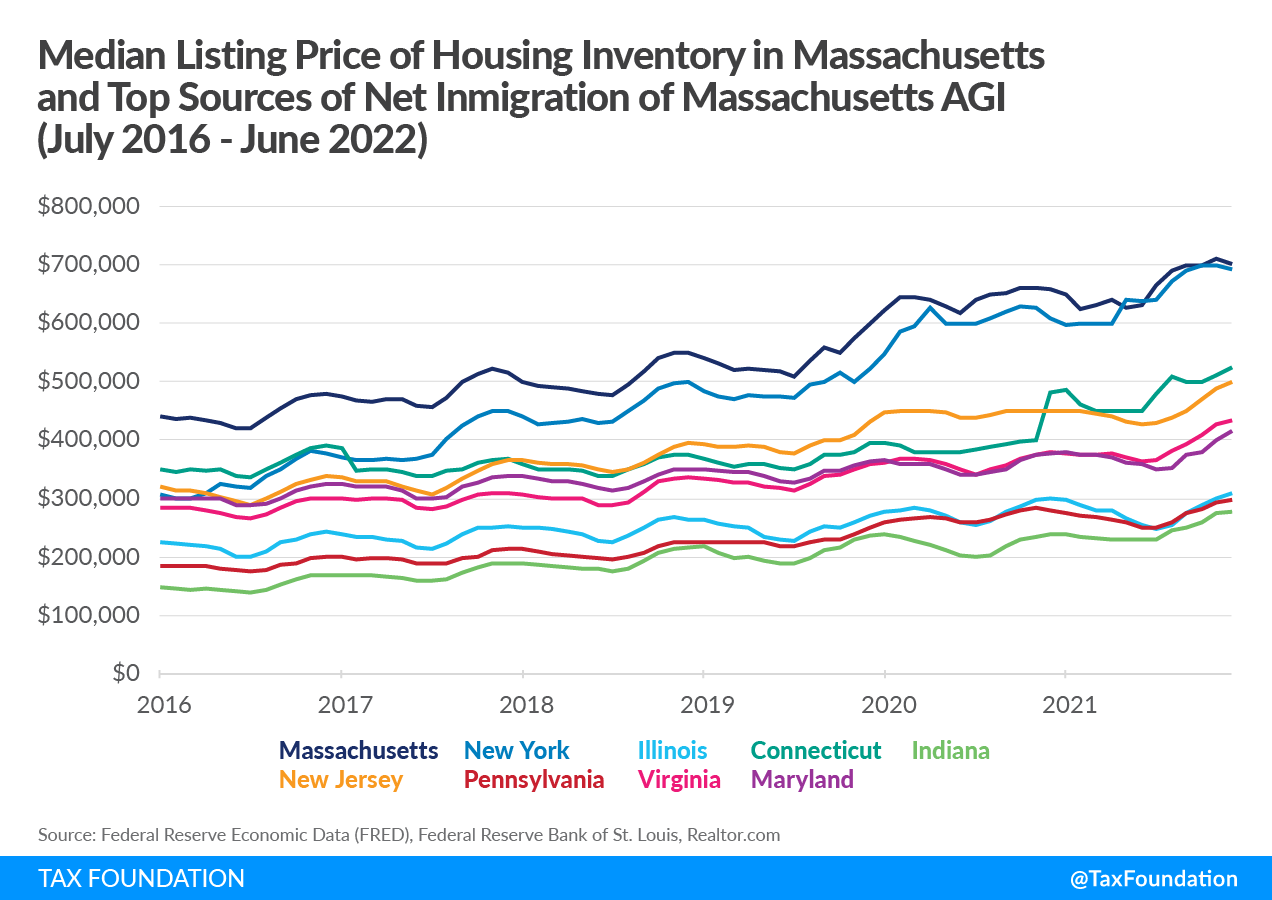

One assertion that is made in the discussion of interstate migration patterns is that housing prices are the driving factor of where to relocate. That seems a plausible conclusion when presented with the median listing price of homes in Massachusetts and the states that made up the top five destinations for net outmigration of Massachusetts residents between 2012 and 2020. As Figures 7 and 8 depict, Massachusetts’ home prices have been significantly higher than every state but California since the turn of the century. But as we will see, there is likely more at play in relocation decisions than just housing prices.

Consider IRS data for net AGI migration from Massachusetts in 2020 (the most recent year for which data is available). The states with the greatest net outmigration by Massachusetts residents in 2020 were Florida, New Hampshire, Maine, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Rhode Island and Vermont broke into the top five for the first time in 2020 (neighboring states are often popular destinations), but Florida has been the top state for net outmigration of Massachusetts AGI every year since 1999, when it was displaced by New Hampshire.

Notably, Florida has no individual income tax and a corporate income tax rate that is only 5.5 percent, compared to Massachusetts’ 8 percent corporate rate. The competitiveness of Florida’s overall tax structure ranked 4th on the State Business Tax Climate Index in 2021 while Massachusetts ranked 34th.

Despite being one of the smallest states in the Union, New Hampshire has been the recipient of the second highest amount of net outmigration from Massachusetts for seven of the last eight years for which data are available. This is especially significant because New Hampshire is a border state to Massachusetts and unlike Florida does not have access to beaches or a year-round warm climate. What it does have in common with Florida is a competitive tax climate. Like Florida, New Hampshire does not tax wage or salary income and its version of the corporate income tax is lower than Massachusetts’. With a ranking of 6th overall, the competitiveness of New Hampshire’s tax structure is very similar to that of Florida’s.

| Rank | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FL | FL | FL | FL | FL | FL | FL | FL | FL |

| 2 | CA | NH | NH | NH | CA | NH | NH | NH | NH |

| 3 | TX | CA | CA | CA | NH | CA | ME | CA | ME |

| 4 | NC | NC | TX | NC | NC | ME | CA | ME | RI |

| 5 | ME | ME | ME | SC | ME | NC | NC | NC | VT |

| Source: IRS SOI Tax Stats-Migration Data, Data Years 2011 to 2020 | |||||||||

For eight of the last nine years, Maine has been in the top five for net outmigration of Massachusetts residents. Ranked 29th on the 2021 Index, it is another New England state that has a more competitive overall tax climate than Massachusetts. Historically, Maine’s overall tax competitiveness has taken a back seat to Massachusetts’, although Maine’s property tax, unemployment insurance, and sales tax structures have been more favorable than that of the Bay State.

There are many reasons why a resident or business may relocate to a particular state. Job availability, proximity to family, more favorable weather, competitive tax policies, affordable housing prices, access to markets, or a more educated workforce may rank near the top. The weight individuals or families give each factor will vary. Some have gone so far as to argue that relocation decisions motivated by the search for a more advantageous tax code are few and far between, if they happen at all.[18]

For many individuals and families, relocation is motivated by employment. United Van Lines’ annual relocation survey consistently finds that people are primarily motivated to move by job opportunities.[19] Either they are relocating with their job, or they found a job in a new state that exceeds the benefits of the status quo. Since businesses must remain competitive and profitable if they are to remain operational, a firm will locate in the viable jurisdiction with the most competitive tax structure, all things being equal. Thus, if an individual or family relocates to pursue employment opportunities out of state, they may not have been consciously searching for a more competitive tax structure, but the more competitive tax structure may have found them. With 43 percent of the income from pass-through businesses in Massachusetts appearing on returns with $1 million or more in income, and with the tax falling on many of the highly mobile executives, entrepreneurs, and investors who create jobs within both C corporations and pass-through businesses, the proposed surtax threatens jobs in Massachusetts for many people who will never pay the tax directly.

Many of the decisions to leave Massachusetts in 2020 were likely facilitated by greater opportunities to work remotely. Rhode Island and Vermont, which respectively ranked 38th and 43red on the 2021 Index, historically have not broken the top 10 for net outmigration locations. Their elevation to the top five is an indication that, while the overall tax competitiveness of Rhode Island and Vermont offers little improvement to that of the Bay State, there were nevertheless significant economic mobility concerns at stake. More affordable housing options in those states is likely a driving force behind the net outmigration number in 2020 and perhaps a desire to move to less densely populated areas, either just for the pandemic or because that lifestyle is now a more viable option. But it is also easier to relocate regionally than it is to relocate across the country—especially in a year defined by a global pandemic.

Every individual’s preferences for location and taxes are different, but the influence of tax policies on people’s relocation decisions becomes more apparent when examining the net migration of AGI from Massachusetts to other New England states. Four of the top five states for net outmigration of AGI from Massachusetts were to New England states: New Hampshire, Maine, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Rhode Island and Vermont broke into the top five for outmigration of AGI for the first time in 2020, which speaks to the behavioral response to the opportunity to work remotely. Some interstate migrants were likely motivated by the more affordable housing options in Maine, Rhode Island, and Vermont than in Massachusetts. The influence of tax policies in those states is less pronounced, but it becomes apparent when we consider AGI movement to New Hampshire and Florida.

The gap between the net outmigration of AGI to Maine and the net outmigration to New Hampshire is chasmic. More than $870 million of net Massachusetts AGI migrated to New Hampshire in 2020 compared to $327 million of net Massachusetts AGI that migrated to Maine the same year.

The influence of tax policies on relocation becomes even more apparent when presented with the IRS’ data for net migration of AGI to Massachusetts. The top five states in 2020 for net AGI migration into Massachusetts all ranked worse than the Bay State on the State Business Tax Climate Index. New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Connecticut, and Illinois ranked 49th, 50th, 44th, 47th, and 36th, respectively, while Massachusetts ranked 35th. In fact, that pattern is consistent as far as back as the Index has comparable statistics.

| Rank | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NY | CT | NY | NY | NJ | NY | NY | CT | NY |

| 2 | CT | NJ | CT | NJ | CT | CT | CT | NY | NJ |

| 3 | NJ | NY | NJ | CT | PA | NJ | MD | NJ | MD |

| 4 | IL | OH | PA | PA | NY | VA | NJ | IL | CT |

| 5 | PA | PA | MD | RI | IN | IL | IL | PA | IL |

| Source: IRS SOI Tax Stats-Migration Data, Data Years 2011 to 2020 | |||||||||

New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey have ranked at least fourth for net inmigration of AGI to Massachusetts every year since 2009. For six of the last nine years, New York was at the top of the list. Connecticut has been second on the list every year since 2012 except for two years when it ranked first and one year when New Jersey took the top spot. Illinois was in the top five for net inmigration of AGI to the Bay State the past four years that data is available and five of the last nine. Pennsylvania, which has had one of the highest corporate income tax rates in the country for decades and was less competitive than Massachusetts on the Index until 2020, was in the top five states for net inmigration of AGI to Massachusetts between 2010 and 2020.

Note the home value index and median listing price of housing in those states, which casts doubt on the theory that home prices alone are behind these migration patterns.

The median listing price for a Massachusetts home is no more similar to the states that are the sources of migration than it was to the states where Massachusetts residents are moving to. The median home value is significantly higher in Massachusetts than it is where people originated.

Data from the IRS and other federal sources suggest that higher-income earners are more responsive to tax increases and more likely to relocate in order to avoid them. This makes intuitive sense, and it is backed up by the literature. High-income earners are also often those who own businesses; they are often job creators. If the high-income earners relocate and take their businesses with them or close entirely, what does that mean for lower-income earners? The relocation of high-income earners could very well mean greater unemployment in Massachusetts.

The Journal of Public Economics published a study by Martin Feldstein and Marian Wrobel in 1998 that investigated how effective progressive state tax systems were at sustaining long-term income redistribution. According to the authors’ research, states are not particularly suited for affecting income redistribution because of how quickly wages adjust to the changing tax environment. Taxpayers’ mobility is a key driver of these wage changes. If a high-earning taxpayer is taxed at an increasingly progressive rate, he or she will either demand a higher gross wage in that jurisdiction or move to a lower tax jurisdiction. As pretax wages of highly skilled individuals rise and wages of low skilled individuals fall, firms are incentivized to reduce the number of higher-paying jobs.[22]

As Feldstein and Wrobel noted, “since individuals can avoid unfavorable taxes by migrating to jurisdictions that offer more favorable tax conditions, a relatively unfavorable tax will cause affected individuals to migrate out until the gross wage for their skill level is raised to a level at which the resulting net wage is equal to that available elsewhere.”[23]

Additionally, there is an entire industry that specializes in tax avoidance. Many Massachusetts taxpayers likely have tax avoidance plans in place at the current 5 percent flat rate. Expect the take up and extent of planning to increase in the face of an individual income tax that will nearly double for the individuals who uniquely have the resources to do extensive tax planning. All tax avoidance planning shares two common features: it is a rational behavior from a self-interested taxpayer, yet it is economically inefficient.

It is important to remember that taxes impact a taxpayer’s behavior. Generally, people attempt to maximize the utility of the income they earn. All things being equal, consumers will purchase goods and services from producers who charge them the least, because they know that the more they pay for one good, the less money they have left over for another. The same is true for taxes which, in the case of sales and use taxes, increase the cost of goods and services or, in the case of income taxes, leave the taxpayer with less money left over to spend elsewhere—now or in the future. If given an opportunity to retain more income, people will do that in an effort to maximize the utility of their income. Thus, it is just as rational for a high-income earner to hire a tax advisor to minimize his or her income from the effects of a 4 percentage point tax increase as it is for someone living in a border town to purchase gas across state lines to save himself 10 cents per gallon in gasoline taxes.

While it may be rational to hire an accountant to devise a maximal tax avoidance strategy, that does not mean it is necessarily macroeconomically efficient to do so. It might be efficient at the individual level; the taxpayer saves more money on taxes than she otherwise would. But there are other opportunity costs that while perhaps difficult to quantify are nevertheless significant.

Consider the amount of time spent by an accountant simply devising a strategy to avoid taxes for a client. That is time that could be spent in support of a company that is producing something of value, something that facilitates the employment and fulfillment of others. Instead, that time is spent simply trying to avoid the impact of an unnecessarily inefficient tax policy. This critique is not intended to denigrate the accounting profession, which is necessary regardless and adds real value. It is simply meant to emphasize the role a simple, neutral tax code has on maximizing economic output and the social welfare.

Who Will Pay the New Tax

One of the purposes of the income tax amendment is said to be getting very wealthy Massachusetts residents to pay their fair share—however that is defined. But the reality is that the tax will also likely affect many “one-time millionaires”—those that through a confluence of events happen to earn $1 million for only one year of their lives. For many small business owners, this could occur at retirement when they sell their companies. For others it could be when they sell their homes that they have been storing after-tax money in for the last 30 or 40 years.

It is not hard to think of a scenario where a modest vacation home becomes a significant tax liability. Consider a couple in their mid-thirties who earned a joint income of $250,000 in 2000. At the time, they purchased a modest vacation home on the Cape for less than $300,000.[24] Nearly 25 years later they are nearing retirement and considering downsizing. Over the years, their joint income increased to $450,000, and, due to significant market appreciation, their vacation home is now worth nearly $900,000.[25] For joint filers, Massachusetts excludes from taxation the first $500,000 of capital gains from the sale of a home, but the exemption only applies to the taxpayers’ primary residence. As a result, when this couple files their taxes they will have a total annual income of $1.05 million and find themselves subject to the surtax as one-time millionaires.

By most standards, this couple’s lifestyle is quite comfortable. It is unlikely to garner much sympathy from the likes of those just trying to save for a down payment on their first home. But the point is not about generating sympathy; the point is about the imprecision and unintended consequences of the surtax. Ostensibly, only those with consistent annual incomes over $1 million—the so-called wealthiest residents—will be subject to the surtax. But many current upper middle-class taxpayers (those earning mid-six-figure incomes) and those who aspire to be could also find themselves subject to the higher tax rate.

If the couple in our example sold their second home today—in 2022—the long-term capital gains on the property would be taxed as regular income at the 5 percent rate. However, if they sold that home under the proposed surtax, the capital gains would be taxed at the new 9 percent rate—an 80 percent increase in the taxes owed.

The capital gains discussion is worth having on a broader basis, because Massachusetts already has one of the highest capital gains tax rates in the country. The Bay State taxes short-term capital gains (gains on capital assets like stocks, bonds, or real estate held for less than one year) at 12 percent. That is the second highest rate in the country, behind California. This disincentivizes the relatively quick turnover of capital investments and incentivizes longer term investments (those held for greater than a year), which are then subject to the 5 percent long-term capital gains rate.

If the surtax is approved, Massachusetts’ long-term capital gains rate will go from the 14th lowest among states that levy the tax to the sixth highest in the country. For Massachusetts investors who earn more than $1 million, the 4 percent surtax would erode nearly all of Massachusetts’ competitive advantage regarding the tax treatment of long-term capital gains. With each structural advantage that is eliminated, the Commonwealth cedes greater tax competitiveness to other states, regionally and nationally.

Another inefficiency of the surtax involves the design of the tax bracket. The threshold at which the surtax will kick in is indexed for inflation, but the surtax imposes a marriage penalty that the Commonwealth lacked previously.

Marriage penalties occur when income tax brackets for married taxpayers filing jointly are less than double the bracket widths that apply to single filers. In other words, married couples who file jointly under this scenario face a higher effective tax rate than they would if they filed as two single individuals with the same amount of combined income.

This non-neutral tax treatment is particularly harmful to owners of pass-through businesses, who pay taxes on their business income under the individual income tax system. Under a marriage penalty, married business owners are subject to higher effective tax rates on their business income than they would be otherwise. Because Massachusetts’ income tax currently lacks multiple brackets, it does not require any adjustment for married couples. But the ballot measure adopts a new surtax for high earners, and the kick-in is the same for singles and married couples.

Although Massachusetts’ overall tax competitiveness ranks below the median, the individual income tax is one bright spot for the Commonwealth. If the 4 percent surtax is approved, Massachusetts’ tax competitiveness will plummet—not just regionally but nationally. As measured by the State Business Tax Climate Index, the individual income tax ranking will drop from 11th to 46th. When the individual income tax interacts with the corporate tax (36th), the property tax (45th), and the unemployment insurance tax (50th), Massachusetts’ overall ranking will decline from 34th to 46th. Massachusetts’ tax structure will become markedly less competitive relative to nearly every other state in the country.

Rising interest rates and ongoing inflation are raising concerns of a recession, which remains a very real fear. Raising taxes during a recession, which the surtax would do, is widely understood to be bad for the economy. Tax increases take money away from businesses that could otherwise use it to expand their productivity by investing in labor and capital, and they take money from consumers who have less to fuel demand.

If tax increases are necessary to fund government the best time to do this is during an economic expansion, not a contraction. However, since the end of the COVID-19 recession, in April 2020, Massachusetts has seen very large revenue surpluses. The surplus in fiscal year 2021 was approximately $1.5 billion, and the surplus in FY 2022 was $4.9 billion.[26] Revenues grew so large in 2022 they triggered an obscure 1986 law that was only implemented once in the last 35 years. Often referred to as Chapter 62F, the law requires the Department of Revenue to refund roughly $3 billion to taxpayers this year. After a period of historically high revenues, it seems an odd time to consider a tax increase that could reverse many of the economic gains made in Massachusetts over the past four decades.

Much of the discussion regarding the benefits of the income tax amendment revolve around the $2 billion in new revenue the surtax was estimated to generate. However, if higher earners adapt their behaviors to the new tax, the potential exists that actual new revenues may fall well short of the $2 billion estimate. Per the amendment, any new money the tax does raise would be earmarked for spending on education and infrastructure. But because money is fungible there is no guarantee that the surtax tax revenue would amount to additional revenue for education and infrastructure—it may just be different money since lawmakers could reduce appropriations for those priorities from existing revenue streams.

Lastly, unlike a conventional tax increase, one enacted through a constitutional amendment is very difficult to reverse. If the tax increase has a negative economic impact on the Commonwealth, it would require another constitutional amendment to lower the rate or repeal the surtax—a process that is measured in years, not months.

Conclusion

Whether Massachusetts needs a new tax on the verge of a new recession and after multiple years of multibillion-dollar surpluses is something voters will decide. As they consider their positions on the tax, they should be cognizant of the many compelling reasons that this surtax could do more harm than good.

Massachusetts’ competitive tax advantage in New England is driven primarily by its competitive individual income tax rate and its sales and use tax structure. If the Commonwealth changes its tax code in ways that narrow the base or increase the rate, it cedes greater tax competitiveness to other states, regionally and nationally.

The proposed surtax is likely to have negative economic effects that will impact low- and middle-income earners. Despite the insistence by some that the tax increase would only impact high-income earners, there is no way to guarantee this. It is no easier to insulate low- and middle-income earners from the economic effects of the income surtax than it is to induce people to stop smoking by banning the sale of menthol cigarettes.

As long as there are alternative markets or ways to shift economic activity to a more competitive state, the surtax is likely to underperform revenue projections and overperform in its malignancy. One reason for this is that the graduated income tax would be paid by many small businesses, in addition to wealthy individuals. According to the application of one academic study, if approved, the graduated income tax could contract the Massachusetts economy by $6 billion by end of 2025.

Massachusetts has struggled with the outmigration of economic activity for decades, but the graduated income tax amendment is likely to exacerbate the net outmigration of AGI from Massachusetts as taxpayers adjust their behaviors to the tax increase. Despite being one of the most tax competitive states in the region, there are many other states with still greater tax competitiveness. Florida and New Hampshire, two states with no individual income tax on wages or salaries, are consistently at the top of the list of destinations for net outmigration of AGI from Massachusetts. That other more tax competitive states, like North Carolina and Texas, also frequently occupy the top of the list of significant destinations for Massachusetts AGI suggests that, while not the only factor in determining location decisions, tax competitiveness does matter.

Responding to potential negative economic effects of the surtax by repealing or adjusting the rate would require another constitutional amendment, which would take years to accomplish. The best solution to avoiding a potentially fraught reversal is to give careful consideration to the full range of economic impacts before it takes effect in the first place.

[1] Jen Wofford, “Massachusetts Begins Round Two in Its Fight to Tax Millionaires,” Inequality.org, Apr. 12, 2019,

[2] Massachusetts border state rankings: New Hampshire—6th; Maine—33rd; Rhode Island—40th; Vermont—43rd; Connecticut—47th; and New York—49th.

[3] Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,” American Economic Review 100:3 (June 2010): 763-801.

[4] Massachusetts’ 2021 gross state product was $636,514,300,000. See FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Gross Domestic Product: All Industry Total in Massachusetts [MANGSP],” retrieved July 7, 2022.

[5] 636,514,300,000 * 0.0094 = $5,983,234,420

[6] Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks.”

[7] See FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Personal Consumption Expenditures: Total for Massachusetts [MAPCE],” retrieved July 8, 2022.

[8] $358,472,300,000 *-0.008164 = -$2,926,567,857.

[9] See Timothy Vermeer, “The Impact of Individual Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth,” Tax Foundation, June 14, 2022,

[10] See GE Press Release, “GE Moves Headquarters to Boston,” Jan. 13, 2016,

[11] Ibid.

[12] Rex Sinquefield, “Fiscal Suicide Connecticut Governor Malloy’s $40 Billion Budget,” Forbes, June 16, 2015,

[13] Edward Krudy, “Immelt asks GE team to weigh Connecticut pullout after tax hike,” Reuters, June 4, 2015,

[14] See United States Census Bureau, Population Division, “Annual and Cumulative Estimates of the Components of Resident Population Change for the United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021 (NST-EST2021-COMP),” modified Dec. 21, 2021,

[15] See Bureau of Economic Analysis, “NIPA Handbook: Concepts and Methods of the U.S. National Income and Products Accounts, Chapter 5: Personal Consumption Expenditures,” modified Mar. 2, 2022,

[16] PIT/TOT = $19.593B/$34.137B. See Massachusetts Department of Revenue Press Release, “FY21 Revenue Collections Total $34.137 Billion,” Aug. 3, 2021,

[17] See Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats – Migration Data,” modified May 24, 2022,

[18] Robert Tannenwald, et al., “Tax Flight Is a Myth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Aug. 5, 2011,

[19] See United Van Lines, “Annual 2021 United Van Lines National Movers Study,” Jan. 3, 2022,

[20] See FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Realtor.com, Housing Inventory: Median Listing Price in Massachusetts [MEDLISPRIMA], Median Listing Price in California [MEDLISPRICA], Median Listing Price in New Hampshire [MEDLISPRINH], [MEDLISPRIME], Median Listing Price in Rhode Island [MEDLISPRIRI], Median Listing Price in Vermont [MEDLISPRIVT], Median Listing Price in North Carolina [MEDLISPRINC], Median Listing Price in South Carolina [MEDLISPRISC], Median Listing Price in Texas [MEDLISPRITX], Median Listing Price in Florida [MEDLISPRIFL],” retrieved July 5, 2022,

[21] See FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Zillow, Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI) for All Homes Including Single-Family Residences, Condos, and CO-OPs in Massachusetts [MAUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], Vermont [VTUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], California [CAUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], Florida [FLUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], Rhode Island [RIUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], Maine [MEUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], New Hampshire [NHUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], South Carolina [SCUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], North Carolina [NCUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID], Texas [TXUCSFRCONDOSMSAMID],” retrieved July 5, 2022,

[22] Martin Feldstein and Marian V. Wrobel, “Can State Taxes Redistribute Income?” Journal of Public Economics 68:3 (June 1, 1998): 369-96.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ethan Zindler and Knight Ridder/Tribune, “Cape Cod home market cools a bit,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 2003,

[25] See Coldwell Banker, “Real Estate Market Trends in Cape Code, MA,” updated Aug. 24, 2022,

[26] Shirley Leung, “A hot real estate market, a labor shortage, and a state budget surplus. It’s 1986 all over again,” The Boston Globe, Aug. 8, 2022,