Long-lost trial transcript answers many questions about ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson and baseball’s ‘Black Sox Scandal’

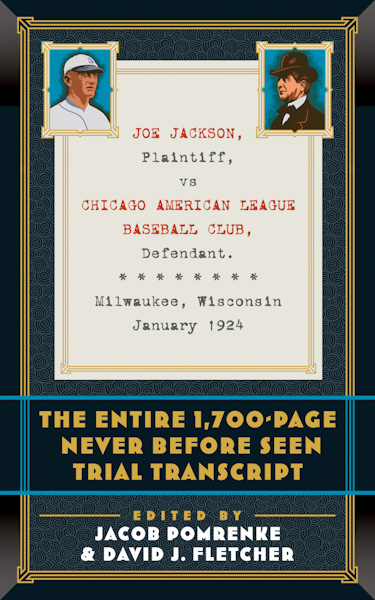

The book opens with a tantalizing revelation: Until this year, fewer than 10 living people have seen the long-lost trial transcript that’s been a matter of public record for a century. It’s from Joe Jackson v. Chicago American League Baseball Club, a two-plus-week trial held in Milwaukee in early 1924.

The proceedings involve Major League Baseball’s stain that has come to be known as the “Black Sox Scandal.” In 1919, the Cincinnati Reds beat the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. The series was fixed. Some players on the Sox conspired with gamblers to throw its outcome. This much is known.

But after that, a debate and search for answers to who was involved, their motivations and how it was pulled off, has resembled whether Oswald acted alone. In the recently published Joe Jackson, Plaintiff, vs. Chicago American League Baseball Club, Defendant—Never-Before-Seen Trial Transcript, its editors promise that the unearthed testimony settles many persistent questions in baseball’s “who killed Kennedy.”

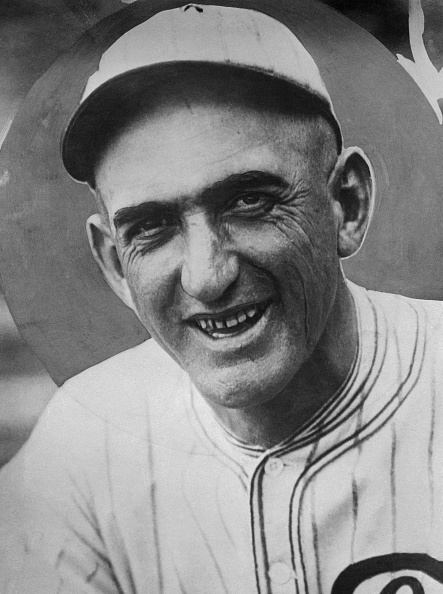

While eight players were implicated in the plot, the brightest light has shone on the role of “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, famously nicknamed for having once played a game in his socks when a pair of new spikes were uncomfortable.

The team’s star outfielder batted .375 during the series, had a then-record 12 hits and made no fielding errors. And he was found not guilty of criminal conspiracy by a Chicago jury. But he was still banned from baseball for life for his believed participation—his many supporters say unfairly so.

But on the eve of this year’s Fall Classic, co-editors Jacob Pomrenke and David Fletcher tell me in an interview that the Bambino-size transcript, weighing in at 4 pounds, 1.6 ounces, puts to rest any doubt that Jackson was squarely involved.

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson, a former Chicago White Sox player, was involved in the “Black Sox Scandal.” Photo by Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images.

Pomrenke and Fletcher point to Eight Men Out as an important source for the misunderstanding over Jackson’s role. The 1988 film, based on author Eliot Asinof’s 1963 book, shows Jackson as illiterate and not involved in the planning of the scheme and who only agreed to participate after the plan was in place. In the film, Jackson is shown in the dugout, prior to the first game of the series, telling Sox manager Kid Gleason that he does not want to play. Gleason orders him to take the field.

While the film shows Jackson as a simpleton, Fletcher says that he was in fact a good businessman who ran a pool hall in Chicago in 1919.

“A lot of people don’t realize that all this new research is out there,” Pomrenke says. “They’re still holding on to the original Eight Men Out story.”

At issue in the civil case was Jackson’s claim against the White Sox for $16,000 in salary remaining under his contract after his baseball career was ended by federal judge-turned inaugural baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The jury found for “Shoeless” Joe. But then came a Hollywood-worthy plot twist.

The 300,000-plus word transcript was uncovered in 1957 by a Milwaukee court clerk during a routine pruning of old files. He called Robert Cannon, the son of Raymond Cannon, Jackson’s lawyer in the case, to offer it to him. Cannon took it. It later made its way to Robert Cannon’s son, lawyer Thomas Cannon.

A copy of the transcript was provided to Jerome Holtzman, a longtime Chicago sports writer, who had recently been named Major League Baseball’s Official Historian. In 2007, Fletcher, a board-certified physician in occupational medicine and founder of the Chicago Baseball Museum, acquired Holtzman’s private papers and books, which included the transcript. Holtzman died in 2008.

With the centennial anniversary of the trial at hand, Fletcher and co-editor Pomrenke—director of editorial content for the Society of American Baseball Research—decided that the time had come to publish the record of the proceedings.

Key to the breach of contract case was Jackson’s September 1920 grand jury testimony where he acknowledged his involvement in the fix. But rather than try to explain-away his prior admissions, he simply denied, more than 100 times, that he ever made the statements contained in his prior testimony:

Question by George Hudnall [lawyer for the White Sox]: “Were you asked this question [before the grand jury] and did you make this answer:

Q: “Did anybody pay you any money to help throw that Series in favor of Cincinnati?”

A. “They did.”

Answer by Jackson: “I didn’t understand the question, sir.”

Hudnall: “The question was:

Q: “Did anybody pay you any money to help throw that Series in favor of Cincinnati?”

A. “They did.”

Hudnall: “Were you asked that question and did you make that answer before the Grand Jury?”

Jackson: “I don’t remember that question at all.”

Twice more, despite his grand jury testimony being read to him, Jackson denied making a statement that anybody had paid money to him to help throw the World Series.

Jackson then proceeded to reject that he had told the grand jury that he had been promised $20,000 to throw the series but was paid only $5,000. Again, he made such denial despite his contradictory grand jury testimony being read back to him.

For Fletcher, the transcript of the civil trial “clearly establishes Jackson’s guilt in the scandal.” In addition to the ballplayer’s admission to getting the money, Fletcher points to the testimony of gamblers involved in the fix, a banker in Savannah, Georgia, who told of a $5,400 deposit made by Jackson’s wife, Katie, on Dec. 1, 1919 (two months after the World Series ended), as well as testimony from Mrs. Jackson on how the money was spent.

While the jury was still out, Judge John Gregory bound Jackson over on a perjury charge. “Jackson stands self-convicted, self-accused,” the judge stated. “[H]is testimony as given here in court has been impeached and shown to be false by the testimony he gave before the grand jury. It makes no difference to me what the jury does.”

“I did not intend,” Gregory added, “to have it go out to people at large that the courts in Milwaukee were so blind that they could not see this flagrant case, or were so cowardly that they were afraid to take action[.]”

But Judge Gregory wasn’t finished. After the jury returned its $16,711.04 verdict for Jackson, the jurist informed them of the perjury charge. Then, in a highly unusual move, he rebuked the jurors for “fail[ing] in the discharge of [their] duty,” adding “how you gentlemen could answer some of those questions [on the verdict form] in the face of that testimony, the court cannot understand.”

The judge set the verdict aside, but Jackson was never prosecuted for perjury.

The Black Sox Scandal remains relevant today, Pomrenke says. “‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson,” owing to Eight Men Out and the 1989 film Field of Dreams—“has become this iconic figure in baseball and American culture. … He was given new life in the 1980s, and that has carried on today. Combine that with the emergence of sports gambling in the last few years being legalized.”

Pomrenke also points to a recent gambling scandal in college baseball and notes that the 2017 Houston Astros World Series sign-stealing scandal has brought up comparisons to the Black Sox Scandal. The developments, Pomrenke tells me, are relevant to “whether we might see another Black Sox Scandal.”

The transcript, Fletcher says, “is the first time that the story is told in such detail. … It reads like a movie script. It’s very dramatic.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.