Justice Thomas questions associational standing; would his view end diversity challenges?

U.S. Supreme Court

Justice Thomas questions associational standing; would his view end diversity challenges?

June 18, 2024, 12:14 pm CDT

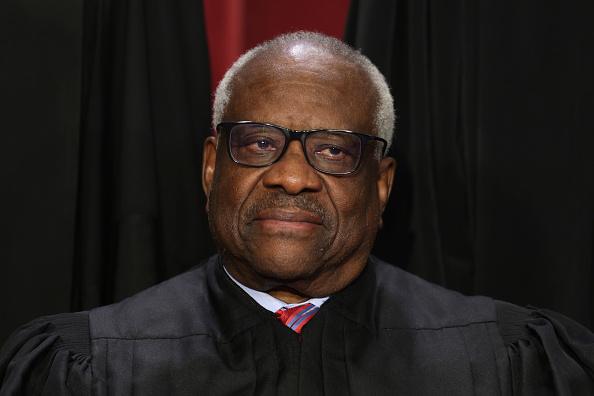

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas poses for an official portrait in the Supreme Court building Oct. 7, 2022, in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Justice Clarence Thomas took a dim view of associational standing in a concurrence last week to the U.S. Supreme Court’s abortion drug mifepristone decision, a stance that could interfere with diversity challenges.

The Supreme Court tossed a challenge to expanded access to the abortion drug because the anti-abortion medical groups and doctors who challenged it lacked standing to sue.

Thomas agreed that the plaintiffs didn’t have standing because they could not demonstrate that they were injured by the policies. He went further, however, when he questioned precedent that allows associations to assert standing on behalf of their members.

Reuters, Newsweek and the Volokh Conspiracy have coverage of Thomas’ concurrence in the June 13 decision, Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine.

The judicial power under Article III is limited to cases and controversies, Thomas said in his June 13 concurrence.

“Associational standing seems to run roughshod over this traditional understanding of the judicial power,” he wrote.

He expressed “serious doubts that an association can have standing to vicariously assert a member’s injury.”

Thomas’ legal theory “would eliminate a spate of recent lawsuits filed by groups that share the conservative justice’s opposition to race-based diversity programs,” according to Reuters.

Thomas questioned cases such as Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising Commission, a 1977 decision that allowed an agricultural agency to challenge an apple shipping regulation on behalf of its members.

The Hunt decision allows an organization to sue on behalf of its members if the members have standing to sue in their own right, if the interests the group seeks to protect are germane to its purpose, and if neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires individual members to participate in the suit.

Federal appeals courts are divided on how much groups must disclose about their members when suing, according to Reuters.

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at New York ruled in March that a group called Do No Harm must disclose the name of at least one member in its challenge to a diversity fellowship by Pfizer.

On June 3, the 11th Circuit at Atlanta ruled that the American Alliance for Equal Rights has standing to challenge a grant contest open only to businesses owned by Black women— even though the alliance used pseudonyms for members who alleged discrimination.

Thomas appears to be embracing the view of Andrew Hessick, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law, who wrote an amicus brief and a co-wrote an upcoming University of Chicago Law Review article on the topic.

Reuters spoke with Hessick. He argued that any person opposed to a law or policy can “manufacture standing out of thin air” by founding a group and recruiting members injured by the law or policy.