Interoperability: Denial or Design? The European Commission’s preliminary findings on Apple’s implementation of vertical interoperability

An exchange of views on a topic is a regulatory dialogue. At least, that’s the first thing that comes to mind. The European Commission’s (EC) idea of a dialogue is very different. Exhibit A is the EC’s publication on its preliminary findings in the two ongoing cases relating the specification of Apple’s technical implementation Article 6(7) i.e. the vertical interoperability obligations (see previous post about the opening of the case here).

The provisions compel the gatekeepers of their operating systems (Windows PC OS Alphabet’s Android, Apple’s iOS and iPadOS), to “allow providers and hardware providers, free of cost, effective interoperability The mandate also gives the gatekeeper a limited scope to take “strictly proportionate and necessary measures” to ensure that the interoperability of its operating system (…), does not compromise the integrity (…), hardware or software. The European Commission, based on this premise and a statement of objections (SO) in EU competition law, released its preliminary findings about how Article 6(7) for Apple’s OS should look when faced with requests from third-parties to access these hardware and software features. In this case however, the decision will not impose punitive measures (for now), but instead a wide range of implementation measures that are necessary to make Article 6.7 effective. Two sets of preliminary conclusions were released. Two sets of preliminary findings were issued: one for each specification case triggered on 19 September 2024 by the EC: DMA.100203

relating to Apple’s features of interoperability with third-party connected devices and DMA.100204 pertaining to its dedicated request. This post considers the bird’s eye view of those preliminary findings, bearing in mind the EC’s exhaustive findings, and building upon the detailed conclusions of my recent working paper on the topic.

The Before and After of Enforcement

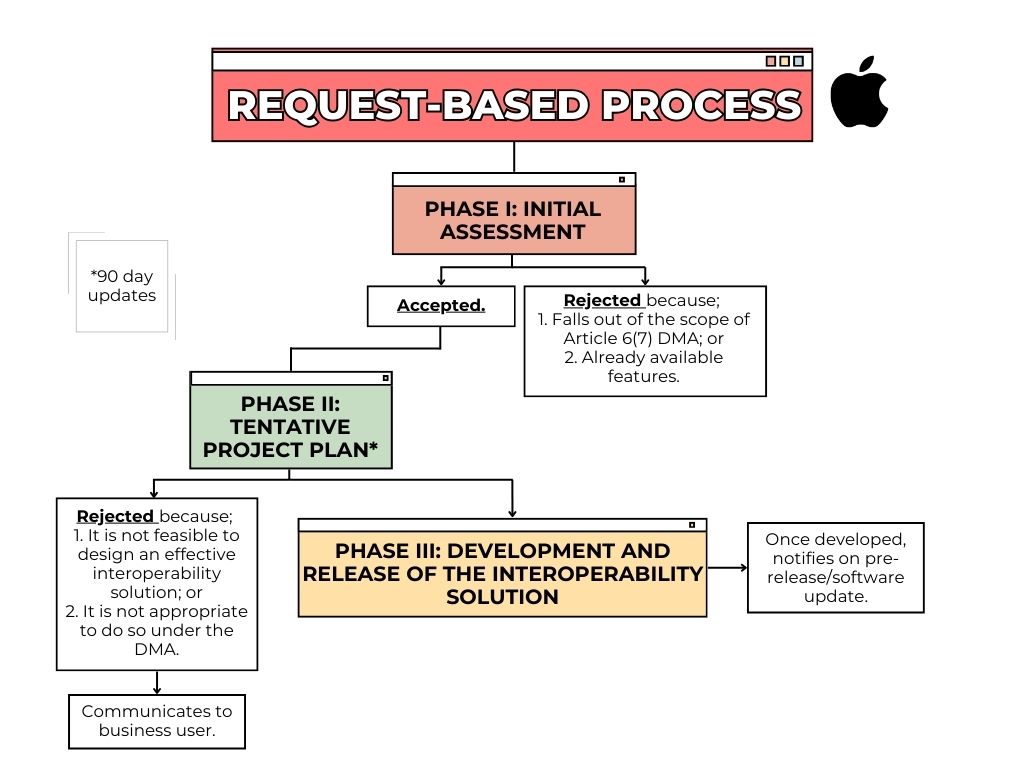

As of March 2024 (aka the DMA’s compliance deadline), Apple presented how it intended to comply with Article 6(7): it would provide business users with the opportunity to send interoperability requests. Apple had a tight hold on the interpretation of the provision after receiving such requests. It could deny requests if they were deemed too complex for its operating system to handle or if they simply fell outside the scope of the provision. Apple was not held responsible for the functioning of the process either, as it only agreed to inform business users of the status of their requests every 90 days. There is little to work with, but plenty of room for improvement. When it released its initial decisions, the EC hinted that it would work to transform Apple’s ecosystem to make it more inviting to business users who wish to interoperate. One of the most interesting passages in those decisions was: “unlike proactive methods such as interoperability-by-design, a request based system can present important limitations and difficulty for third parties.” (… and) it enables the gatekeeper to maintain control over (the) outcome (of the interoperability requests), i.e., whether, when and how interoperability will be provided” (para 20 of the decision in case DMA.100204

).

In its preliminary findings, the EC went one step further. Apple’s vertical solution for interoperability is not only below the threshold set by design for interoperability, but also creates inherent limitations and risks (paragraph 2 of the case DMA.100204 preliminaries findings). In this sense, the EC preempts Apple’s request based process as a unfair and ineffective path to interoperability. The statement reveals a very clear parallelism. Market power weakens competition structures and the dominant player has a special obligation to not harm or hinder competition. The enforcer reflects this building block in the application of Article 102 TFEU, and explains that implementation measures must follow from this general concept. The EC argues that the implementation measures included in its preliminary findings are all based on this general presumption, which is in line with the principles relating to necessity and proportionality (paras 8 & 9). Case DMA.100203 is all about substantial changes and transformations that Apple must abide by with regards to functionalities enabling third-party physical connected devices to interoperate with iOS and case DMA.100204 revolves around the

(messed-up) scheme of Apple’s initially proposed request-based process. The Commission actually relies on this request-based approach to present its own idea for effective enforcement. The difference between Apple’s previous compliance proposal and the implementation measures is striking, as shown below in Figures 1 & 2. Apple’s request based process as presented and designed by Apple in March of 2024.

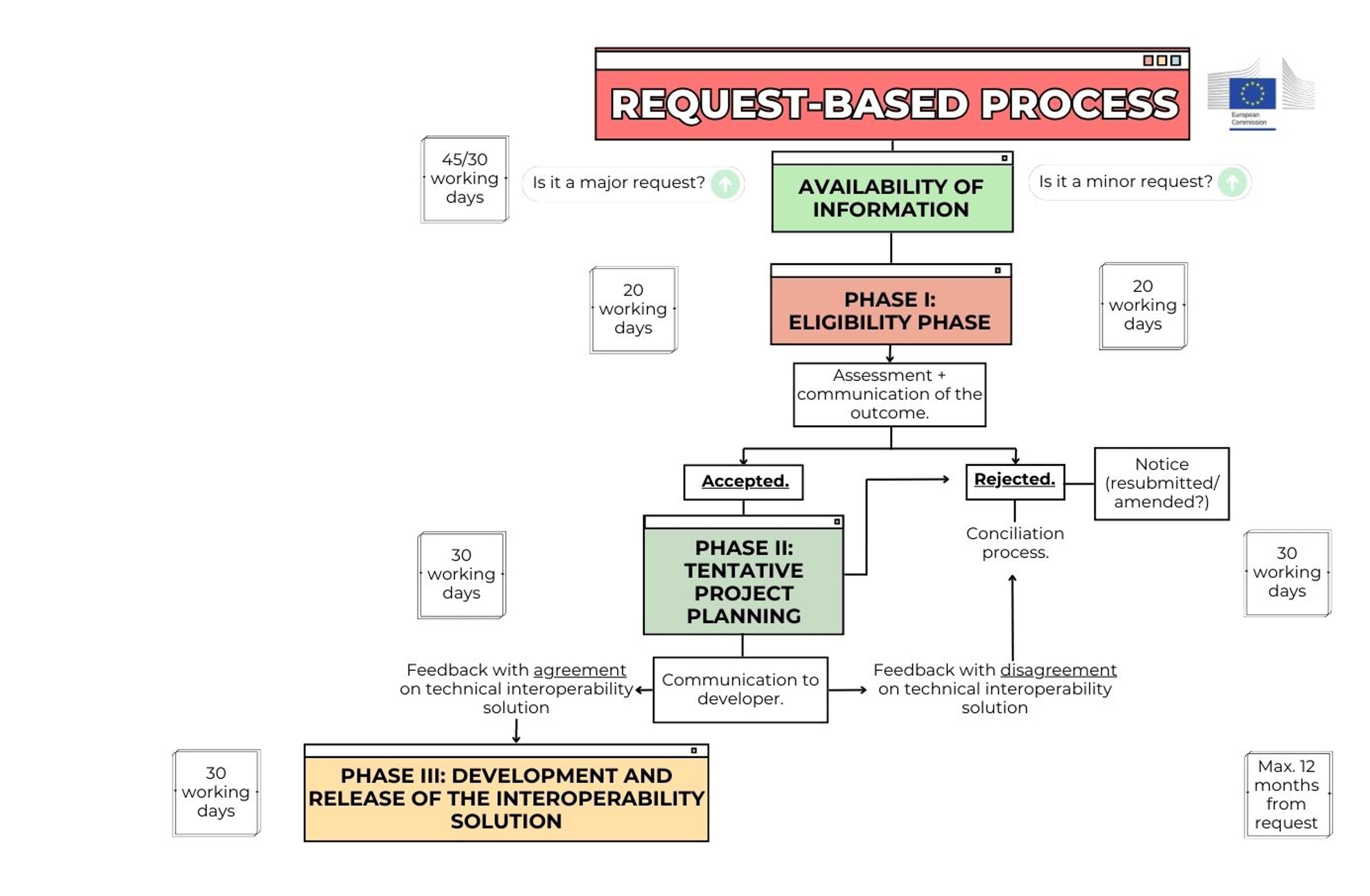

Figure 2 below shows the EC’s efforts to transform Apple’s sub-par proposal -on effective interoperability- to, at least, accommodate the principles of transparency and fairness into the request based process. Figure 2 below, however, shows the EC’s efforts in transforming Apple’s sub-par proposal -on effective interoperability- to, at least, accommodate the principles of transparency and fairness into the request-based process.

Figure 6. Figure 6. The European Commission’s preliminary findings on the functioning of Apple’s request-based system, paras 12 to 76 (case DMA.100204).

Figure 2 shows the many prongs and tenets the EC introduces to the mix via its preliminary findings, including a whole set of deadlines that the gatekeeper must abide by to comply with Article 6(7) DMA.Additionally, the EC includes a pre-notification-like phase to the whole procedure, termed ‘Availability of Information’ in the graph. Before the EC’s findings, it wasn’t entirely clear how developers would avoid having their requests rejected because interoperability solutions were readily available. In other words, there was no way for them to find out from Apple that such solutions existed. The EC will now require Apple to provide developers with information about reserved features and functionality accessed or controlled via iOS and iPadOS, so that they understand their purpose. This information will also describe whether or not certain features and functionality are reserved for Apple and what conditions, restrictions, or entitlements they apply to (para 12). According to the Commission access to this information is necessary for developers to understand the extent of reserved features and functionality, i.e. those features that may require an interoperability resolution (para 18). Apple’s compliance solution was reactive, which meant that developers could only resubmit their request by changing some aspects (in the hopes that it would be accepted). The EC’s preliminary findings draw a clearer picture where the developers are continuously in contact with the gatekeeper, especially in the most critical phases of the process, e.g., the actual development of the interoperability solution.

Moreover, the EC introduces, in a similar fashion to the DSA-style out-of-court dispute settlements, a conciliation process by which gatekeepers and developers may address their disagreements and disputes with the assistance of a neutral third party (para 43). The EC introduces a conciliation process to resolve technical aspects of a request. For example, when Apple wants to implement an interoperability system that developers find too restrictive, or when developers disagree with the complexity of the interoperability solutions (para 45). Apple’s initial 90-day update is not sufficient to meet the DMA’s threshold for effective enforcement. The EC has responded to this issue by introducing a variety of different mechanisms that ensure information flows quickly and freely to developers. Apple, for example, should establish a designated contact to ensure that developers receive timely assistance with any issues that may occur during the assessment and implementation process of their requests. (para 28). Gatekeeper will also introduce a tracker system which provides developers with up-to date and easily accessible information via a dedicated section of Apple’s developer portal. (para. 69).

All the technical implementation measures related to the request-based processes nail down how interoperability works. Parallel to this, however, the EC elaborates on the general ideas presented in both Recitals 56 and 55 DMA. These interpretative provisions give a guide on how the legislator intended the vertical interoperability requirement to be enforced in practice. The Recital 55 highlights wearable devices as an area of improvement for interoperability. In a similar vein, Recital 56 pinpoints some of the functionalities required for the effective provision of a service catered together with a third-party device, notably near-field-communication technology or authentication mechanisms.

Instead of interpreting the principles of transparency and fairness, the enforcer draws into the meaning of the ‘equally effective’ threshold required by Article 6(7) DMA. The EC explains its implications in relation to the features and functionality that Apple must make available to business users so that they can compete with Apple’s connected devices. This includes its smartwatch, Apple Watch, and its headsets, Apple Vision Pro and AirPods. The EC’s long list is purely of a technical nature. This is for good reason as this is how innovation will reach the end user. Third parties will be able to create compatible and interoperable devices, such as smart TVs and wearables, with the iPhone and iPad, thanks to a range of features. Users will, as a result, not be ‘stuck’ to using Apple’s digital ecosystem consistently, but they will, at least be provided the choice to pick competitor products, hypothetically bringing prices down for third-party connected physical devices.

Aside from the de facto extensive rules that the EC establishes per each of the 11 features to flesh out the meaning of effective interoperability, the enforcer sets out some ground rules applying transversally to all features. The EC begins by stating that interoperability must be granted to third parties in a way that is technically sound and practical, without undue barriers. In the same vein, the gatekeeper must adhere to a set measures that are generally applicable to maintain the mandate of effective Interoperability. They are both positive (prescriptive) and negative (proscriptive) in nature.

Relating to the former, the EC puts pen on paper to avoid recognising a general right to interoperability for all developers. Business users will have access to certain hardware and software features if they show an interest in using them for a specific purpose. Interoperability is not a goal in itself. In accordance with the implementation measures on the request-based process, the gatekeeper must know what, how and why the business user needs interoperability to provide adequate access in line with fairness. According to the implementation measures for the request-based system, the gatekeeper is required to know what, how, and why the business users need interoperability in order to provide access that is fair. The EC, despite the fact that interoperability doesn’t necessarily mean equality, makes this statement true by requiring the gatekeeper to meet a high level of compliance. This includes ensuring that the same conditions and effectiveness are applied across all dimensions, including the end-user journey, ease of use, software and device setup, data transmission speeds, and energy consumption. Building on its previous experience with Apple’s DMA compliance solutions incorporating friction into the end user journey, the enforcer requires the gatekeeper to make all interoperability solutions frictionless, away from security and safety prompts and complex defaults to access the rights available as per the regulation.

In terms of the proscriptive measures, the preliminary findings reiterate the obvious: the gatekeeper cannot introduce restrictions on the interoperability solutions catered to business users when those limitations stem from the type or use case of the app or the connected physical device. In the same vein, the enforcer embeds the anti-circumvention provision embedded in Article 13 DMA in the implementation measures, declaring that the gatekeeper can’t undermine effective interoperability of the 11 features by its technical behaviour. The EC chose to add new reporting obligations on top of the existing Article 11 and Article 15 compliance and auditing mandates for the gatekeeper. The EC has added three new compliance obligations for third-party connected devices:

The measures taken by the gatekeeper to comply with the specification decisions, including a detailed description of interoperability solutions and justifications on how they establish effective interoperability in conditions equal to those available to Apple’s services and products.

The potential APIs and technical details made available to third party as a result of the interoperability solutions (a nonconfidential report will be publically available);

10 Apple will be required to issue an updated report every six months (para. 79). Apple will also be required to report all the steps it has taken to comply to the specification decision (paragraph 85).

Gatekeeper response and the enforcer’s style of regulation

On the 19th December, the EC published its preliminary findings regarding both specification proceedings. Apple published its note termed ‘It’s getting personal: How abuse of the DMA’s interoperability mandate could expose your private information

‘, a five-page manifesto directly criticising the EC’s stance on the effective vertical interoperability mandate and, especially, fellow gatekeeper Meta’s vested interests in promoting access to hardware and software features ‘for all’ (

but really, for its own sake

). See, for example, Figure 3 below, a screenshot of information Apple included in the memo.

- Figure 3 Apple’s response to the European Commission preliminary findings is shown in a screenshot.

- Meta Communications Director Andy Stone responded shortly

- afterwards on X, arguing that Apple’s concerns about privacy “have no basis” and “they don’t think in interoperability”. The gatekeeper feud was just one of many acts in the contemporary tragedy that Apple has been putting on stage for years about privacy. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. If the EC’s preliminary findings were unambitious or left loads of discretion for Apple to decide on what features it should provide access to, then the reaction would have been less flamboyant.

However, this aspect does not make the EC’s style in issuing these preliminary findings impeccable, either. The hopes that many of us had for the DMA to provide a clear communication channel between the regulator and regulatory targets have long since been dashed. The non-punitive-inspired mechanism of the specification does not set out an adequate path for holding a regulatory dialogue. The specification allows the EC to state the implementation measures that it wants the gatekeepers to follow, and that is it. It is true that the EC gave a period for public consultation (from 19 December until 9 January, happy

ruined

holidays, business users), but the process will not crystallise into anything similar to transparency. Apple will receive the comments from the EC so that they can respond to the preliminary findings and make any necessary adjustments to their final decision based on feedback received. The feedback will not be made public on the EC’s website, so that the public can learn what influences were used to draft the final version of the decision or how responsive the EC is to such feedback. As I explained in my paper on the topic, the DMA doesn’t directly hinder this possibility (

nor supports it, to be honest). The EC has, however, decided to turn those specification proceedings into a guidebook that it then passes on to the gatekeeper. This is at least what’s immediately obvious from the initial findings. The enforcer has once again re-established its role as sole enforcer of the DMA by displaying great discretion in not only what the DMA will look like, but also how it can be most successful.