In re Cellect (Fed. Cir. 2023) | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

The Federal Circuit decided a question left open during a recent spate of opinions involving the judicially created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (ODP): the effect patent term adjustment (PTA) can (or should) have on creating circumstances where ODP will operate to find a patent invalid in the absence of a timely filed terminal disclaimer, in its opinion handed down yesterday in In re Cellect.

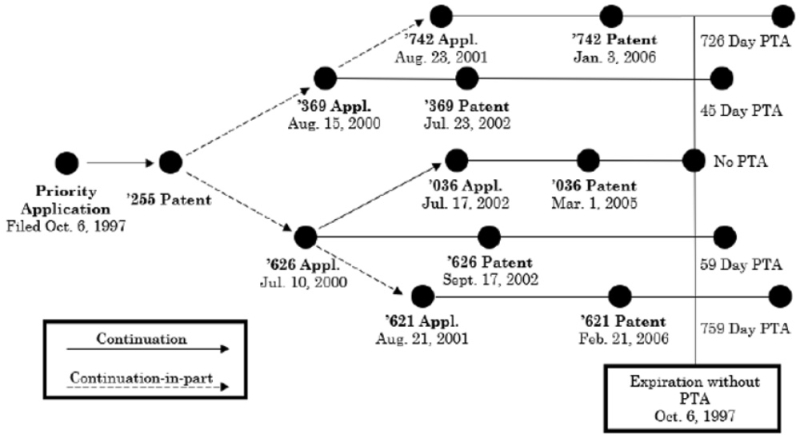

The issue arose in a series of ex parte reexaminations over five patents owned by Cellect, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,424,369; 6,452,626; 6,982,742; and 7,002,621, that involve “solid state image sensors which are configured to be of a minimum size and used within communication devices specifically including video telephones” according to the ‘621 patent (only four of these patents were invalidated, the fifth, U.S. Patent No. 6,862,036 not having any PTA that raised the issue). The chronological situation is set forth in an exhibit from Cellect’s brief in its Federal Circuit appeal brief and reproduced in modified form in the opinion:

The opinion also set forth the chain of invalidation under obviousness-type double patenting, stating that:

[T]he ‘621 patent claims were found to be unpatentable over the ‘626 patent claims, which were found to be unpatentable over the ‘369 patent claims. The ‘742 patent claims were also found to be unpatentable over the ‘369 patent claims. The ‘369 patent claims were themselves found to be unpatentable over the ‘036 patent claims. Thus, although the ODP invalidating reference patents form a network across the four ex parte reexamination proceedings, all invalidated claims can be traced back to the single family member patent that did not receive a grant of PTA: the ‘036 patent.

There was no dispute that the claims in these applications were patentably indistinct. The Board issued four Decisions on Appeal affirming the reexamination division’s invalidation of the ‘369, ‘626, ‘621, and ‘742 patents, all on the grounds that the provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(B):

No patent the term of which has been disclaimed beyond a specified date may be adjusted under this section beyond the expiration date specified in the disclaimer . . .

mandated that a terminal disclaimer be filed under circumstances where obviousness-type double patenting arose due to extension of patent term as PTA, i.e., that ODP must be determined after application of PTA. (It will be recalled that the Federal Circuit reached a different conclusion with regard to patent term extension (PTE) under 35 U.S.C. § 156 in Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC, the Court expressly refusing to permit “a judge-made doctrine to cut off a statutorily-authorized time extension.”) Because all of these patents had expired (but Cellect retained the right to sue for prior infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 286), the Board’s decision invalidated these patents with no available remedy left for Cellect. In its consolidated decision, the Board emphasized the potential inequities to the public due to the possibility of harassment by different parties owning patents to obvious variants of one another (in the absence of a terminal disclaimer preventing this potentiality) as representing an unjust extension of patent term to the public’s detriment; see In re Fallaux, 564 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2009)). Finally, the Board rejected arguments that the Federal Circuit’s jurisprudence did not rely on whether or not there was gamesmanship or the potential thereof under Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd, but that under In re Longi, the public was entitled to the assumption that it is free to practice what is claimed in the patent and obvious modifications and variants thereof once the patent has expired. 759 F.2d 887 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s judgment in these re-examinations in an opinion by Judge Lourie joined by Judges Dyk and Reyna.* Although patentee asserted five arguments in its briefing, the Court discussed only three of these arguments (albeit in some instances apparently condensing the five arguments to three).

The first argument which was dispositive for the Court in its affirmance was Cellect’s position that PTA under 35 U.S.C. § 154 and PTE under 35 U.S.C. § 156 should be treated equivalently as Congressional mandates that should not be abridged by judicially created doctrines like obviousness-type double patenting. The Court’s opinion to the contrary was based on three principles. The first was that it is inequitable to the public that a second patent, later-expiring patent should be obtained (“an unjustified timewise extension of patent term”) on an obvious variant of a patented invention, based on AbbVie Inc. v. Mathilda & Terence Kennedy Inst. of Rheumatology Tr., 764 F.3d 1366, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2014). The panel’s opinion found support in the statute (as had the Board), wherein application of PTA was limited under circumstances where there was or should have been a terminal disclaimer filed (35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(B)): “Disclaimed term.— No patent the term of which has been disclaimed beyond a specified date may be adjusted under this section beyond the expiration date specified in the disclaimer” (emphasis in brief). There is no such limitation in 35 U.S.C. § 156 and even though both statutes recite that an extension of the term shall be granted this distinction between the two types of extension was enough to convince the Court that the Board had come to the correct conclusion.

This conclusion was based in part by the Court’s precedent, particularly AbbVie, and by the panel’s agreement with the distinction in statutory construction between 35 U.S.C. § 154 and § 156 as advocated by the Solicitor representing the USPTO. The overriding policy consideration is the Court’s focus on the need to “ensure that the applicant does not receive an unjust timewise extension of patent term” (as it has for over a decade; see “In re Janssen Biotech, Inc.; G.D. Searle LLC v. Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.”; “AbbVie Inc.”; “Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd.”; “Eli Lilly & Co. v. Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc.”; and “Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. v. Eli Lilly & Co.”). The fact that the limitations of terminal disclaimers is in the PTA statute but not the PTE statute indicates to the Court that Congress intended the effect of ODP to differ between these two approaches to statutory term restoration. They “are dealt with in different statutes and deal with differing circumstances” and while “the expiration date used for an ODP analysis where a patent has received PTE is the expiration date before the PTE has been added” pursuant to Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC (Fed. Cir. 2018), and Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., 482 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2007), the “expiration date used for an ODP analysis where a patent has received PTA is the expiration date after the PTA has been added” as the holding in this case. Cellect’s argument that both PTA and PTE should be treated equally because they “provide statutorily authorized time extensions” is “an unjustified attempt to force disparate statutes into one” according to the opinion.

The panel perceived differences in the statutes (“each has its own independent framework established through an independent statutory schema”) that justify the distinctions raised in this opinion despite the similarities that “both PTA and PTE are statutorily authorized extensions, and each serves to recover lost term,” because they have “quite distinct purposes.” Importantly, the panel construes the statute in this manner because for them “[t]here is nothing in the PTA statute to suggest that application of ODP to the PTA-extended patent term would be contrary to the congressional design.” On the contrary, the Court understands Cellect’s position to “effectively extend the overall patent term awarded to a single invention contrary to Congress’s purpose” (which is to limit an extended term for a patentably distinct invention). In the panel’s view, the overriding consideration is “to ensure that the applicant is not receiving an unjust extension of time.”

Finally, in this regard, the Court understands that if terminal disclaimers are the solution to the problem of unjust extensions of time precluded by ODP, permitting PTA to apply where a terminal disclaimer has not been filed (to avoid application of 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(B)) would “frustrate the clear intent of Congress [by permitting] applicants to benefit from their failure, or an examiner’s failure, to comply with established practice concerning ODP” (i.e., using terminal disclaimers to avoid invalidation).

The opinion refuses to find the equities asserted in Cellect’s second argument arising from the particular circumstances in this case to be a basis to come to a different conclusion than the Board had. The Federal Circuit recognizes the preeminent policy purpose for applying ODP to the PTA circumstances in this case like every other. If, as the Board asserted and the Federal Circuit agreed, Cellect’s patents received an “unjust timewise extension” of their patent term, the absence of gamesmanship does not remedy these circumstances nor excuse Cellect from the consequences arising therefrom (“it does not matter how the unjustified extensions are obtained”). Moreover, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that a risk continued to exist regarding the other consideration in ODP, the possibility of separate ownership of patents that are not patentably distinct (no matter Cellect’s promises that it would not alienate them, nor how remote or theoretical these risks might be).

Finally, the Federal Circuit rejected Cellect’s third argument that the re-examinations were improvidently granted because there was no substantial new question of patentability raised in them, based on the same examiner being responsible for permitting these patents to grant and not issuing a rejection in any of them based on ODP. The panel found that institution of these re-examinations was supported by substantial evidence because, inter alia, there was nothing in the prosecution history of any of these patents that “affirmatively indicates that the examiner considered whether or not an ODP rejection should be made.” The Court also rejected the alternative proposed by Cellect of only considering the adjustment term, and not the entire patent term, for invalidation as an attempt to have the PTO or the Court grant a “retroactive” terminal disclaimer, giving Cellect “the opportunity to benefit from terminal disclaimers that it never filed.”

While we have come a long way from the conventional use of terminal disclaimers to protect the public from shenanigans of intentional delay by doling our patentably indistinct variations on an invention to extend protection beyond the statutory 17-year term prior to revision of the patent stature in response to U.S. accession of the GATT/TRIPS agreement, the philosophy applied by the Court in this decision is consistent with that judicial attempt to prevent “unjust” extensions of patent rights. Of course, there are stratagems existing and to be developed to adapt to the regime established by the Federal Circuit’s decision, which only reinforces the value of the clever draftsman in protecting important technologies under creative applications of the law as the Federal Circuit construed it in this case.

* In June, the Court affirmed the Board’s judgment under Rule 36 in Reexamination No. 90/014,452 and Cellect, LLC v. Samsung Electronics Co. in inter partes review proceedings IPR2020- 00475, IPR2020-00476, IPR2020-00477, and IPR2020-00512.

In re Cellect (Fed. Cir. 2023)

Panel: Circuit Judges Lourie, Dyk, and Reyna

Opinion by Circuit Judge Lourie