In far cry from usual textualism, court rejects veteran’s attempt to reopen a benefits denial based on legal error

OPINION ANALYSIS

on Jun 17, 2022

at 10:08 am

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that a VA benefits decision that was based on an agency regulation in effect at the time the decision was rendered does not constitute “clear and unmistakable error” even if the agency regulation is later deemed to conflict with the text of the relevant benefits statute. As a result, a veteran whose benefits claim was denied based on the later invalidated regulation may not seek to reopen his benefits denial under a statute that authorizes collateral review of veterans’ benefits decisions on grounds of “clear and unmistakable error.”

Before diving into the court’s opinion in George v. McDonough, it is worth recalling a little background about the case and its complicated intersection of statutory provisions, regulations, and agency and judicial decisions. Recall that the relevant veterans benefits statute provides that the United States will pay compensation to a veteran who is disabled as a result of injuries or diseases that are “contracted in the line of duty” or for “aggravation of a preexisting injury suffered or contracted in the line of duty.” A different provision of the statute establishes that “every veteran shall be taken to have been in sound condition” at the time of enrollment unless “clear and unmistakable evidence demonstrates that the injury or disease existed before acceptance and enrollment and was not aggravated by such service.” A longstanding Department of Veterans Affairs regulation, in effect for 20 years, established that a “veteran will be considered to have been in sound condition when examined, accepted and enrolled for service” unless “clear and unmistakable (obvious or manifest) evidence demonstrates that an injury or disease existed prior thereto” — leaving out the statutory phrase “and was not aggravated by such service.” In 2003, the VA’s general counsel concluded that the regulation was inconsistent with the text of the statute, insofar as it failed to require clear and unmistakable evidence to rebut the presumption that a veterans’ injury or disease was aggravated by his military service; a year later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reached the same conclusion, ruling that “the government must show … both a preexisting condition and a lack of in-service aggravation to overcome the presumption of soundness.”

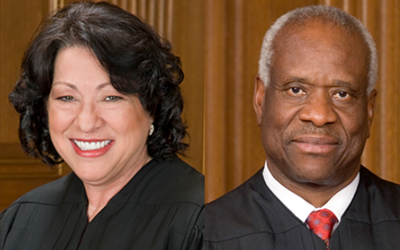

In 2014, veteran Kevin George asked the Board of Veterans’ Appeals — an administrative body within the VA — to revise its final decision denying his claim for benefits on the basis of pre-existing paranoid schizophrenia that had been aggravated by his service, based on yet another statutory provision that allows veterans to seek revision of a final benefits decision at any time on grounds of “clear and unmistakable error.” The board denied George’s claim and the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims affirmed. The Federal Circuit also affirmed, concluding that the application of a later invalidated regulation does not fall into the category of “clear and unmistakable error” permitting revisions of a final decision. The Supreme Court agreed, in an opinion authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett and joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, Sam Alito, Elena Kagan, and Brett Kavanaugh.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Barrett’s opinion for the court (and the two dissenting opinions from Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch) is how little it focuses on the text of the relevant statutes. Barrett’s opinion does nod at the text, observing that the modifiers “clear” and “unmistakable” indicate that only a narrow category of errors are covered by the statute. The opinion also cursorily notes that the “statutory structure” suggests a narrow construction of covered errors because the provision creates an exception to the norm of finality for veterans benefits decisions.

But Barrett quickly sidelines these text-based observations as “general contours” and moves on to her principal argument, which is that “a robust regulatory backdrop fills in the details” of the statute’s meaning. Specifically, Barrett argues that the phrase “clear and unmistakable” error is a term of art — i.e., a term with a specialized legal meaning. In this case, Barrett claims that “clear and unmistakable error” is a phrase that “ha[s] a long regulatory history” and concludes that Congress deliberately codified that longstanding history and meaning when it employed the phrase in the statute at issue. Barrett goes on to explain that longstanding agency practice and precedent establish that the term “clear and unmistakable” error does not encompass subsequent “changes in law” or “changes in the interpretation of law” — and that the Federal Circuit ruling invalidating the agency regulation upon which George’s denial decision was based is a mere “change in the interpretation of the law.”

The court’s reliance on agency practice — a pragmatic, atextual interpretive source — is surprising, as is its emphasis on Congress’ supposed expectation that that agency practice would be incorporated, or codified, into the relevant statute. Indeed, the majority’s focus on past agency practice stands in marked contrast to its decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor, the case decided earlier this term involving a federal COVID-19 policy for large private employers. In that case, the court ruled that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration exceeded its authority when it imposed a vaccine-or-test mandate on those employers because the mandate sought to regulate a hazard (the transmission of COVID-19) that is not workplace-related and that occurs outside, as well as inside, the workplace. In so ruling, the court ignored past agency practice in the form of numerous prior OSHA decisions regulating workplace hazards such as exposure to asbestos or bloodborne pathogens, or fire, that are not hazards exclusive to the workplace. Similarly, the court’s presumption that Congress meant to codify the VA’s longstanding agency practice of treating “changes in the interpretation of law” as insufficient to constitute “clear and unmistakable error” is noteworthy because it puts the court in the position of essentially speculating about legislative intent — a move that the textualist justices usually denigrate.

Gorsuch, joined by Sotomayor and Justice Stephen Breyer, dissented. Gorsuch’s dissent argues that a benefits decision based on an agency regulation that conflicts with the text of the relevant benefits statute necessarily constitutes “clear and unmistakable error” — because a regulation that conflicts with a statute’s text has always been incorrect, including at the time the benefits decision was rendered. In so concluding, Gorsuch relies on the fact that the review-granting statute was written in the present tense, that it did not incorporate language contained in VA regulations indicating that errors resulting from “changes in interpretation” do not count as “clear and unmistakable,” and that Congress’ “whole purpose” in setting up this provision was to make an exception to the usual rule of finality for veterans “in recognition of their service to the Nation.”

Sotomayor joined all but Part II-C of Gorsuch’s opinion, writing separately to indicate that she agreed with the majority that Congress had codified pre-existing regulatory doctrine establishing that “clear and unmistakable error” does not encompass a “change in interpretation of law” — but that she disagreed with the majority’s reasoning about what constitutes a “change in interpretation of law.” Citing different Veterans Court decisions than the majority, her opinion opines that pre-existing regulatory doctrine was “unsettled” on the question of whether judicial invalidation of a regulation that squarely conflicts with a clear statutory text constitutes a “change in interpretation of law.” Given this ambiguity, Sotomayor turns instead to the veterans benefits canon — a policy canon that presumes that “provisions for benefits to members of the Armed Services are to be construed in the beneficiaries’ favor.” Based on this veteran-friendly canon, she would have allowed George to reopen his claim.