Impact on Manufacturing & Small Businesses

Though the recent debt ceiling deal reins in discretionary spending, it does not include significant fixes to the tax code. One still-outstanding tax issue is research and development (R&D) amortization, which has a dampening impact on investment across the economy and a disproportionate effect on tech, manufacturing, and small businesses.

To reduce the revenue impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), policymakers introduced the amortization of research and development expenses, scheduled to take effect at the end of 2021. Under R&D amortization, companies must spread their deductions for R&D expenses out over five years for domestic R&D and 15 years for foreign R&D, instead of deducting them immediately. Because of the tax code’s accounting conventions, domestic firms ultimately have to deduct 10 percent of costs in year one, 20 percent of costs each year in years two through five, and the remaining 10 percent of costs in year six.

Making taxpayers spread research and development deductions out means that companies cannot deduct the full cost of investment thanks to inflation and opportunity cost. Companies value present deductions more than future deductions because a deduction now means tax savings can be reinvested. Under the half-year convention, assuming a 3 percent discount rate and 2 percent inflation, companies would only be able to deduct 88.3 percent of domestic R&D investment. Higher inflation means an even larger tax penalty: under 5 percent inflation, a company could deduct just 82.8 percent of its costs.

To justify an investment, companies must earn a high enough expected return. R&D amortization means companies are unable to deduct their full costs, which increases the cost of capital and the required rate of return for a company to make an investment. As a result, R&D amortization leads to lower R&D investment on the margin as fewer investments can meet the higher required expected return.

Less investment has a negative impact on the economy in the aggregate. It also has a disproportionate impact on sectors and industries reliant on R&D investment, namely information technology and manufacturing. In 2019, manufacturing and information technology invested a combined $357 billion in research and development, accounting for 83 percent of the $429 billion in private domestic research and development investment that year. Research and development is also concentrated in specific sub-industries; chemical manufacturing, computer and electronics manufacturing, software publishing, and transportation equipment manufacturing combined for over half of domestic research and development performed and paid for by companies in 2019.

Policymakers have targeted support at many of the same industries in the past year, with the CHIPS and Science Act providing a new tax credit for semiconductor investment and the Inflation Reduction Act subsidizing green energy technology manufacturers. Amortizing research and development undercuts that support.

R&D amortization also creates liquidity problems for small businesses. By forcing businesses to spread out deductions over several years, R&D amortization taxes income that does not exist.

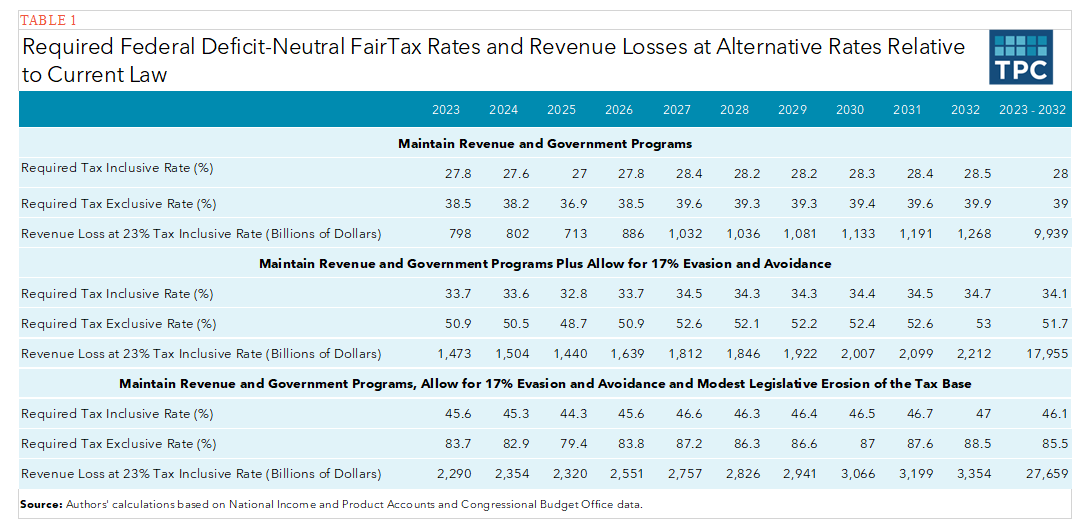

Figure 1: Sample Comparison of Company Under Expensing and R&D Amortization| Tax Liability under Expensing | Tax Liability under R&D Amortization | |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $ 275,000.00 | $ 275,000.00 |

| Deduction for Operating Costs | $ 225,000.00 | $ 225,000.00 |

| Deduction for R&D Investment | $ 50,000.00 | $5,000.00 |

| Taxable Income | $ – | $ 45,000.00 |

| Tax Liability (Assume 21% Tax Rate) | $ – | $9,450.00 |

|

Source: Author’s Calculations. |

||

Imagine a business has $5,000 in cash on hand at the beginning of the year, and, over the course of the year, it earns $275,000 in revenue, has $225,000 in operating expenses, and invests $50,000 in research and development. The business breaks even, meaning it has no profits to tax. Additionally, it ends the year still with $5,000 in cash on hand.

On the other hand, under R&D amortization, the business would only be able to deduct $5,000 this year under the half-year convention, meaning it will report $45,000 in taxable income and owe $9,450 in taxes. But that taxable income does not exist, and the business only has $5,000 in cash on hand at the beginning of the year, so it would need to borrow money to pay the tax liability. Now, a large company with a strong credit rating might find this a relatively minor inconvenience. But for small businesses or startups with limited access to capital, the situation is a much larger hurdle.

Reporter Richard Rubin of The Wall Street Journal highlighted the struggles of several small businesses in handling the change. Some taxpayers are using the R&D tax credit to help mitigate the large tax bills they owe due to amortization, but the credit itself is difficult for small businesses to access. Back in 2013, the Small Business Administration analyzed what share of certain tax breaks went to small businesses and found that small businesses benefitted much more from expensing research and development than using the credit. The credit is complex and difficult to navigate relative to simply deducting the cost of R&D.

The current tax treatment of R&D expenses is irrational, complicated, and counterproductive. Policymakers ought to let companies fully write off R&D expenses immediately. Fortunately, fixing this problem is a bipartisan issue, as Senators Maggie Hassan (D-NH) and Todd Young (R-IN) recently reintroduced a bill to restore expensing for research and development, among other changes to R&D tax treatment.

.jpg?width=300&height=202&name=shutterstock_1095344882(1).jpg)