Hughes Dissents in Partial Win for Inventor Against Google at CAFC

“We ultimately conclude that the representative claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents are directed to an abstract idea, but that, on the pleadings, they satisfy step two of the Alice test.” – CAFC

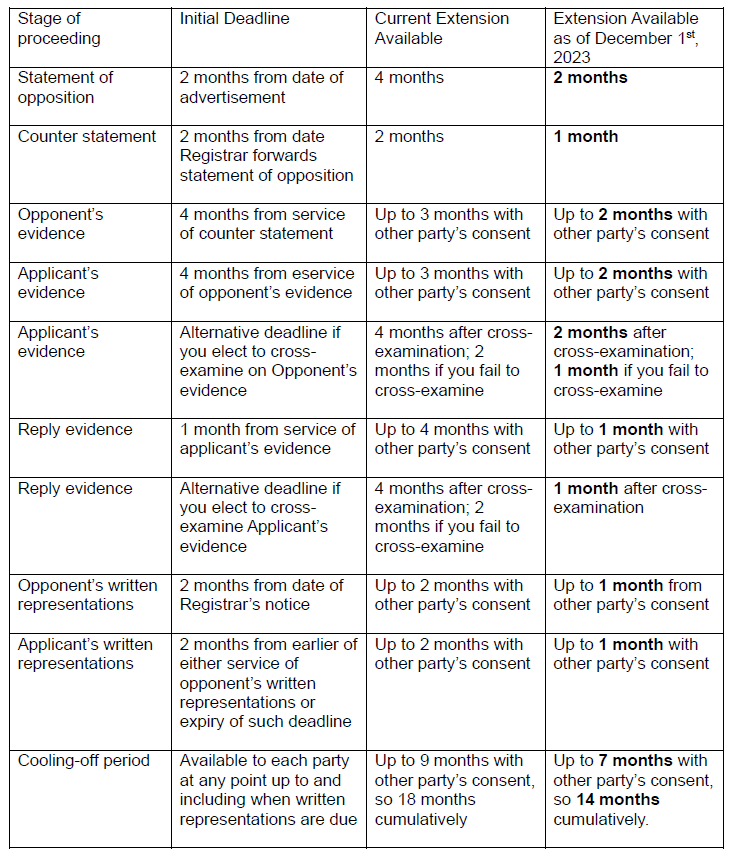

Image from CAFC opinion

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) today issued a precedential decision in part reversing and in part affirming a district court’s dismissal of an inventor’s patent infringement suit against Google under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure12(b)(6). Judge Hughes dissented in part from the majority’s opinion, which was authored by Judge Stoll, explaining that he would have found all of the challenged claims patent ineligible.

Sholem Weisner owns U.S. Patent Nos. 10,380,202, 10,642,910, 10,394,905 and 10,642,911, which are all generally related to “ways to ‘digitally record a person’s physical activities’ and ways to use this digital record.” The patents share a specification, but their claims are “meaningfully different,” said the CAFC. While representative claims 1 of the ‘202 and ‘910 patents are similar and focus on “recording ‘physical location histories’ of ‘individual member[s]’ that visit ‘stationary vendor member[s]’ in a ‘member network’” and “accumulation of physical location histories,” respectively, the representative claims of the ‘911 and ‘905 patents deal with “using physical location histories to improve computerized search results.”

Google argued that all of the claims were ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and that Weisner had failed to meet the minimum threshold for plausibly pleading his claim of patent infringement. The district court ultimately granted dismissal on both grounds.

Creation of a Digital Travel Log Fails Alice

The CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims of the ‘202 and ‘910 patents were directed to the abstract idea of “collect[ing] information on a user’s movements and location history [and] electronically record[ing] that data.” The court explained of claim 1 of the ‘202 patent: “The steps in the body of the claim describe a generic process for achieving the goal of creating a digital travel log, such as “maintaining a processing system” and using an “application” to generate a user’s “location history entry” on their “handheld mobile communication device.” And the preamble to claim 1 of the ‘910 patent “likewise recites a ‘method for accumulation of physical location histories.’” Furthermore, the body of the claim recites generic features such as processing system that is connected to a telecommunications network,” a “URL,” and a “handheld mobile communication device,” said the court.

While Weisner attempted to argue that the claims “improve the functionality of the underlying system,” the CAFC agreed with the district court that “[h]umans have consistently kept records of a person’s location and travel in the form of travel logs, diaries, journals, and calendars, which compile information such as time and location.” Weisner’s argument that the claims are not abstract because they focus on capturing the travel history only of “members” was also unpersuasive, said the CAFC:

“[T]hese purported technological advantages are nothing more than attorney argument, unlinked to the complaint or the patent claims or specification. Indeed, neither the specification nor the SAC addresses this purported technological improvement.”

For similar reasons, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims failed at Alice step two, and failed to “recite significantly more than the abstract idea of digitizing a travel log using conventional components.”

Still Abstract, But Plausibly Eligible Under Step Two

However, turning to the remaining patent claims, the CAFC said the district court erred first in considering all of the patents together, rather than distinguishing the claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents from the ’202 and ’910 patents. At step one, the CAFC found the ‘905 and ‘911 patent claims to be directed to “creating and using travel histories to improve computerized search results,” and although the majority ultimately concluded this to be an abstract idea, the claims survive because they satisfy step two:

“Whether these claims are directed to an abstract idea presents a much closer question than the claims in the ’202 and ’910 patents. We ultimately conclude that the representative claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents are directed to an abstract idea, but that, on the pleadings, they satisfy step two of the Alice test. Thus, we proceed to step two.”

At step two, the court found that Weisner “plausibly alleged” that the claims recited a specific implementation of the abstract idea “that purports to solve a problem unique to the Internet,” and that the claims should therefore not have been held ineligible at the Rule 12(b)(6) stage. The district court held the claims ineligible at step two because the “patents at issue . . .confirm that the patented search and data collection uses conventional techniques without an inventive concept,” specifically that “the patentee did not invent a new search engine algorithm.” But the CAFC said that while this proves the search engine algorithm can’t be the inventive concept, it doesn’t mean the claims are ineligible:

“As explained below, we conclude that the claims’ specificity as to the mechanism through which they achieve improved search results (through a “location relationship” with a “reference individual” for the ’905 patent or through the “location history of the individual member” who is running the search in a targeted “geographic area” for the ’911 patent) is sufficient.”

The court also said the specific implementation allegedly solves a problem particular to the internet and, citing DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014), that “we have previously held patent claims eligible at step two when they provided a specific solution to an Internet-centric problem.” The CAFC found the claims here analogous to those in DDR.

Dissent Distinguishes DDR

Judge Hughes, however, disagreed with the majority on this point and dissented-in-part, explaining that “[b]ecause the second amended complaint admits that the algorithms used to incorporate location data are routine and conventional, and because the claims do not solve a problem specific to the internet, I would affirm the district court’s determination that the claims of these two patents are ineligible.”

Hughes distinguished the claims from those upheld in DDR because the claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents do not solve a problem specific to the computer realm. Hughes said:

“[T]he problem of overly generic recommendations predates the internet, as does the solution of using location information to improve recommendations. To get more personalized recommendations from a travel agent, people could ask about specific destinations and list locations they have visited before, analogous to the method of the ’911 patent. To get more personalized restaurant recommendations, people could ask friends with similar tastes who have visited some of the same restaurants, like the ’905 patent.”

The claims in DDR were directed to “a system in which a visitor to a webpage that clicked on an advertisement on that webpage would not be transported to the third-party advertiser’s page but instead would remain within the original host’s webpage, allowing the host to retain web traffic.” This is different from Weisner’s claims because the DDR claims “’overc[a]me a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks’ that does not have the same close analogues in the physical world—one cannot be inadvertently lured away from a physical retail store with the press of a button.” Weisner’s claims, on the other hand, “merely recite the performance of some business practice known from the pre-Internet world along with the requirement to perform it on the Internet,” concluded Hughes.