From Huawei/ZTE to Apple/Optis, Europe Has Become a Friend to Patentees

“Overwhelmingly, right now, I would say that hold-out is the bigger issue…. I’m not sure hold-up is nonexistent…but I still think that when a company puts a lot of effort into R&D, they have to be paid for that. It’s the honest thing to do.” – Inna Dahlin

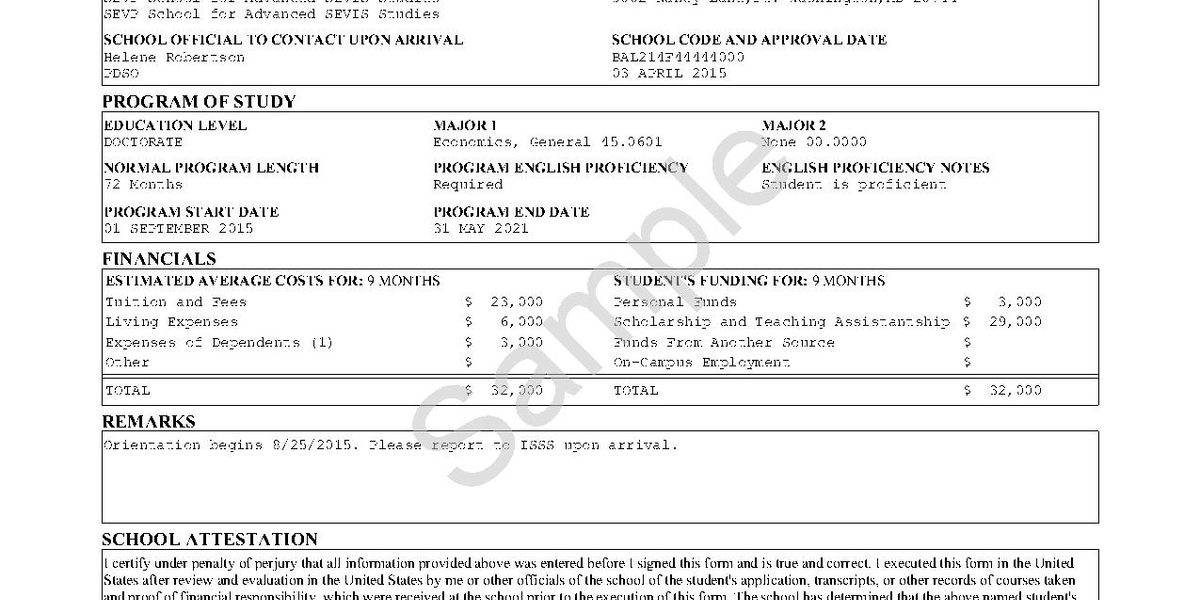

From left: Gene Quinn, Thomas Gniadek, Kayleigh Nauman and Inna Dahlin

During IPWatchdog’s Standards, Patents & Competition Masters 2022 program last week, one panel examined the standard essential patent (SEP) landscape in Europe, which has become decidedly more patent owner friendly than that of the United States in recent years.

Beginning with the landmark 2015 decision by the European Court of Justice in Huawei v. ZTE, ([2015] EUECJ C-170/13), European courts have held SEP holders and implementers to account by applying the framework set forth in that ruling, which panelist Inna Dahlin of Valea AB summarized for attendees.

“First, the SEP holder should put the infringer on notice; next, the infringer should express willingness to negotiate; and then, if willingness is expressed, the SEP holder should offer the FRAND [fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory] license and the implementer can make a counter-offer,” Dahlin explained. If this framework is followed, then the SEP holder is deemed not to have violated competition law under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and not to have abused its dominant market position by bringing an action for an injunction against the alleged infringer.

Courts in Germany, the United Kingdom, Netherlands, France and Italy have been generally following this framework, despite some differences in interpretation. However, as certain stakeholders has since indicated in their responses to the EU Commission’s recent call for evidence, some may be uncomfortable with the high standard for willingness on the part of implementers. Both the Commission and the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) are presently conducting reviews of their SEP regimes.

Determining FRAND

Europe and the UK have seen many other interesting developments, both on the policy front and in the courts, since the Huawei judgment. One of the most debated cases is the decision by the UK Supreme Court in Unwired Planet v Huawei (UKSC 37, [2020]), which has been a hot topic for its finding that the UK courts are an appropriate forum for determining worldwide FRAND rates. However, IPWatchdog Founder and CEO, Gene Quinn, who was moderating the panel, noted that this is not an entirely accurate portrayal of what happened in the case. “The judge said, ’you can either have an injunction in the UK or we can settle the worldwide license,’ because that’s how these things are licensed—globally,” Quinn explained. “I don’t think the UK court was going out of its lane to be the master of the world.”

Dr. Thomas Gniadek of Simmons & Simmons agreed with Quinn, and said the perception that UK courts are better than German courts for getting a global determination of a license fee is “a gross misunderstanding.” While the mechanisms may be different, German courts are very plaintiff-friendly when it comes to SEP cases, Gniadek said. “In the UK, courts are focused on the calculation determination, while in Germany, they’re focused on the injunction.” But generally speaking, Gniadek said, German courts are a safe bet for SEP owners.

For instance, with respect to the ever-elusive question of whether “FRAND” is a rate or a range, Gniadek said the German case law shows definitively that it’s a range and has applied a very clear test for determining license rates:

“The parties come up with two numbers, and then the judges assess the willingness of the implementer—that’s a big hurdle. Most cases are resolved at this point. If the implementer isn’t willing, that’s it. If it is, then the judge would look at the FRAND offer presented by the patentee, and if that offer is within that FRAND range, then the judge would say, ‘this is a FRAND offer and the implementer needs to accept it.’ And even if the implementer comes up with another number that’s also FRAND, sorry, that doesn’t help.”

In one notable case, following a six-year long legal dispute between Sisvel and Haier, the German Federal Court of Justice in 2020 established a high standard for a defendant to be considered a willing licensee. The Court also held that a SEP holder can combine SEPs with non-SEPs without violating antitrust law and can offer different rates to different licensees. “It’s not necessarily groundbreaking case law, it’s just expressing what a willing licensee is,” explained Gniadek. “It says both parties are required to truly negotiate a FRAND license and take active steps to agree.”

Additionally, earlier this year, the German courts further clarified that implementers must show willingness both before and during litigation and must help to agree on a FRAND license. If there is any indication of unwillingness at any point, an injunction can issue.

Upcoming Policy Changes

Kayleigh Nauman (left) and Inna Dahlin

Also joining the panel was Kayleigh Nauman, Intellectual Property Attaché for North America at the UKIPO. Nauman explained that the UK is “looking with fresh eyes at how it fits into the global landscape now that we no longer are part of the EU.” As part of that reevaluation, the country is examining its SEP regime. The UK government released an innovation strategy in July 2021, with the goal of establishing the UK as a dominant player in innovation by 2035. In December 2021, right around the time a new draft of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) Joint Policy Statement on SEPs was released (and later withdrawn), the UKIPO released its own call for comments. The results of that were published in August 2022, but no action has yet been taken. “We’ll be sending findings of the review to our minister by the end of 2023, and that will continue to be wrapped up into an ongoing review of EU legislation still on the books and any potential changes that might be made in the future,” Nauman said. Since the comments received so far were largely contradictory, Nauman said there’s a need to continue stakeholder engagement in order to get a more holistic picture. “It’s hard to make policy changes based on a number of contradictory opinions,” she noted.

In another policy-side development, in January 2021, after two years of debate, the EU Group of Experts on Standard Essential Patents issued a Report focused on SEP licensing, and particularly on a level of the value chain of a product at which licenses should be granted. Despite some interesting proposals, out of 79 total, no consensus on recommendations has been reached. And more recently, as mentioned above, in 2022, the European Commission accepted submissions from the public regarding a new European Union SEP and competition law framework, with a reform planned for 2023.

Hold-Up and Hold-Out

As with most of the panels held during the SEP Masters program, speakers also touched upon the contentious issue of “hold-up” (delay by patent owners) versus “hold-out”(delay by implementers). Dahlin said that, while it’s a complicated topic, “overwhelmingly, right now, I would say that hold-out is the bigger issue.” There is more empirical evidence of hold-out but, of course, implementers often have a “diametrically opposite view,” Dahlin added. “I’m not sure hold-up is nonexistent…but I still think that when a company puts a lot of effort into R&D, they have to be paid for that. It’s the honest thing to do.”

The UK Court of Appeal recently weighed in on hold-up and hold-out in Optis v. Apple. While the Court ultimately came out on the side of the patent holder, Lord Justice Arnold also expressed frustration with both sides, and with the state of the system for determining SEP/FRAND disputes more generally. He wrote: “Apple’s behaviour in declining to commit to take a Court-Determined Licence…, and their pursuit of their appeal, could well be argued to constitute a form of hold out…; while Optis’ contention that an unqualified injunction should be granted would open the door to hold up. Each side has adopted its position in an attempt to game the system in its favour.”

While this does not necessarily summarize the entire state of SEP-related affairs in Europe and elsewhere, a lot remains to be resolved by participants of the SEP universe and by the courts. As we look toward 2023 and beyond, Gniadek said it will be interesting to watch how the new Unified Patent Court will deal with SEP cases, while both Dahlin and Nauman underscored the importance of stakeholder participation in the ongoing reviews in the UK and EU. But for now, Gniadek said that – in Europe at least – “the global battle on SEPs and FRAND has been won by patentees, and that wasn’t a given. There have been many chances for the EU commission to intervene and raise antitrust issues, but they haven’t done that with SEPs. I find it pretty amazing.”