Frenemies in the GenAI Playground?

By most indicators, the Generative AI or GenAI ecosystem is a dynamic and competitive space. GenAI is estimated to generate $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion in value for the global economy. There has been a substantial influx of venture capital investments backing innovative start-ups. Since ChatGPT launched in 2022, there are now more than 310 large language models (LLMs) (the technology underpinning ChatGPT) developed by 94 different organizations. These include notable startups like OpenAI and Anthropic, many of which have achieved unicorn status, often with significant backing from existing players like Microsoft, Amazon and Google. Apart from being a cutting-edge technology itself, GenAI is also generating new opportunities across various markets and disrupting the dominance of established companies – for instance, in the search engine space, the dominance of Google is being challenged by the GenAI offerings of Perplexity AI, CoPilot in Bing and SearchGPT.

Despite these indicators of a thriving and competitive landscape, earlier this year, the competition watchdogs in US, UK and EU issued a joint statement, advising caution and highlighting concerns about competition risks in the GenAI market. Several competitions authorities have highlighted risks to competition, and the majority of submissions to the EC’s call for contributions (“EC submissions“) have echoed these risks. So, what explains these divergent stances on the state of competition in the GenAI market? What are the risks to competition, and do we have evidence that they are likely to occur? If yes, what should be done about them? There is a peculiar characteristic of digital markets, not limited to GenAI, which might hold the key to some of the answers – “frenemy dynamics”. In this post, I will address the questions above in turn, starting with what “frenemy dynamics” mean.

What do frenemy dynamics mean in the context of GenAI markets?

As early as 2016, almost six years before the launch of ChatGPT, Ezrachi and Stucke used the term “frenemy dynamics“ in the context of another digital market – mobile and tablet apps – which was dominated by Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android platforms. It was used to describe the complex interactions of cooperation and competition that was emerging between the super-platforms and app developers. On the surface, this market appeared competitive, where cooperation between the two led to pro-competitive features, such as lower search costs (where customers could find the best offerings using price comparison websites and customer reviews) and fewer barriers to entry (where businesses could easily set up an online presence through apps to directly interact with customers).

However, Ezrachi and Stucke warned that the competitive facade masked a more complicated picture due to the extent to which the platforms are integrated in the market – where entry was possible, but expansion would be controlled by the entrenched market power of a few super-platforms; choice was ample, but competition would be limited due to leveraging practices like self-preferencing, tying and bundling; and disruptive innovative threats could emerge, but would be eliminated through killer acquisitions and exclusionary practices. These dynamics were likely to remain hidden due to intellectual capture, where the platforms dominated the academic conversation about these issues by funding favourable studies and reports that helped maintain the facade.

The warnings came true – both Apple and Google went on to engage in extractive and anticompetitive practices like mandating the use of its payments system for e-books and audiobooks, requiring the pre-installation and use of its apps as a condition of accessing the app store, and prohibiting smartphone manufacturers from using non-approved versions of its operating system. The consensus is that competition authorities did not act fast enough to address these practices, making it more challenging to deal with them later.

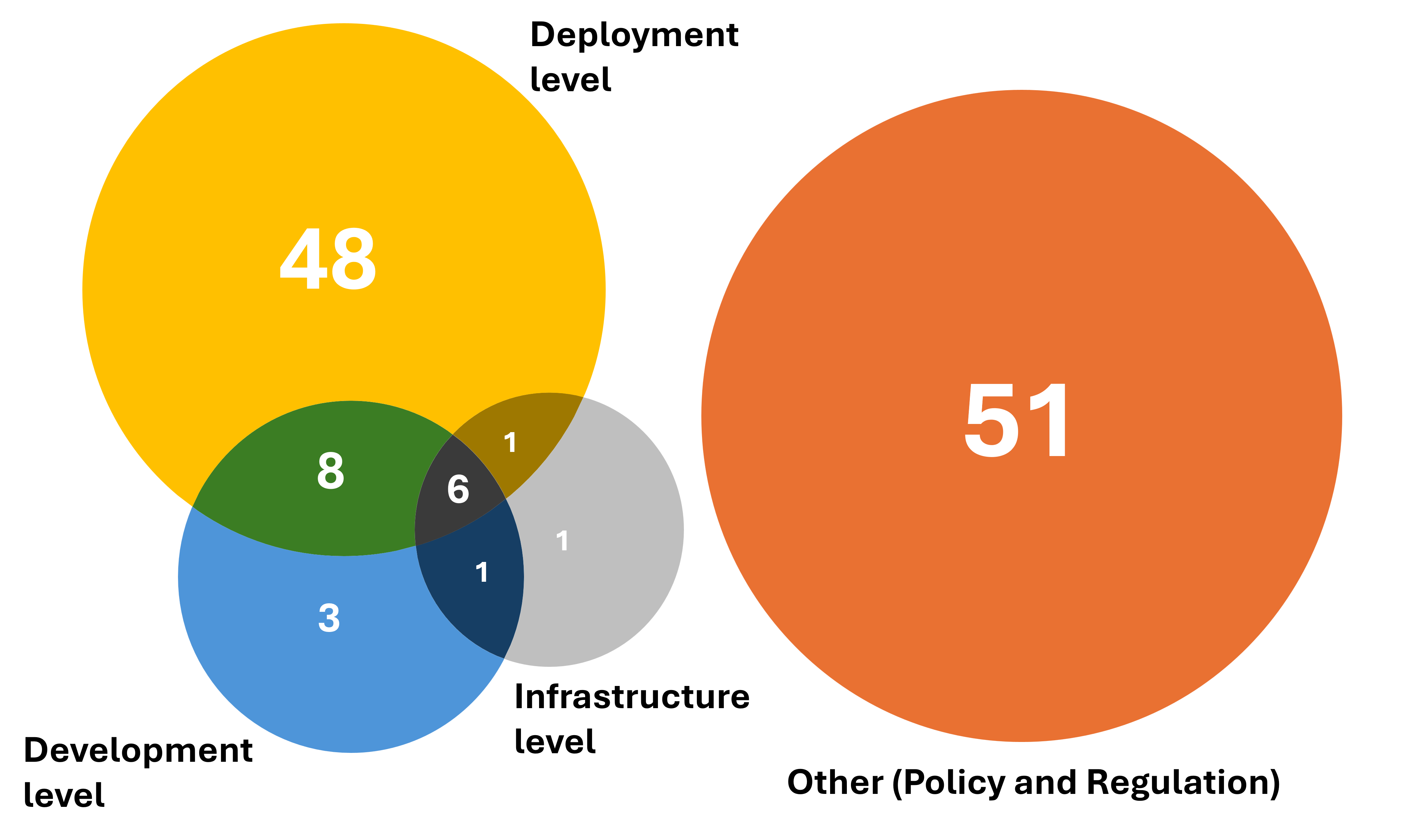

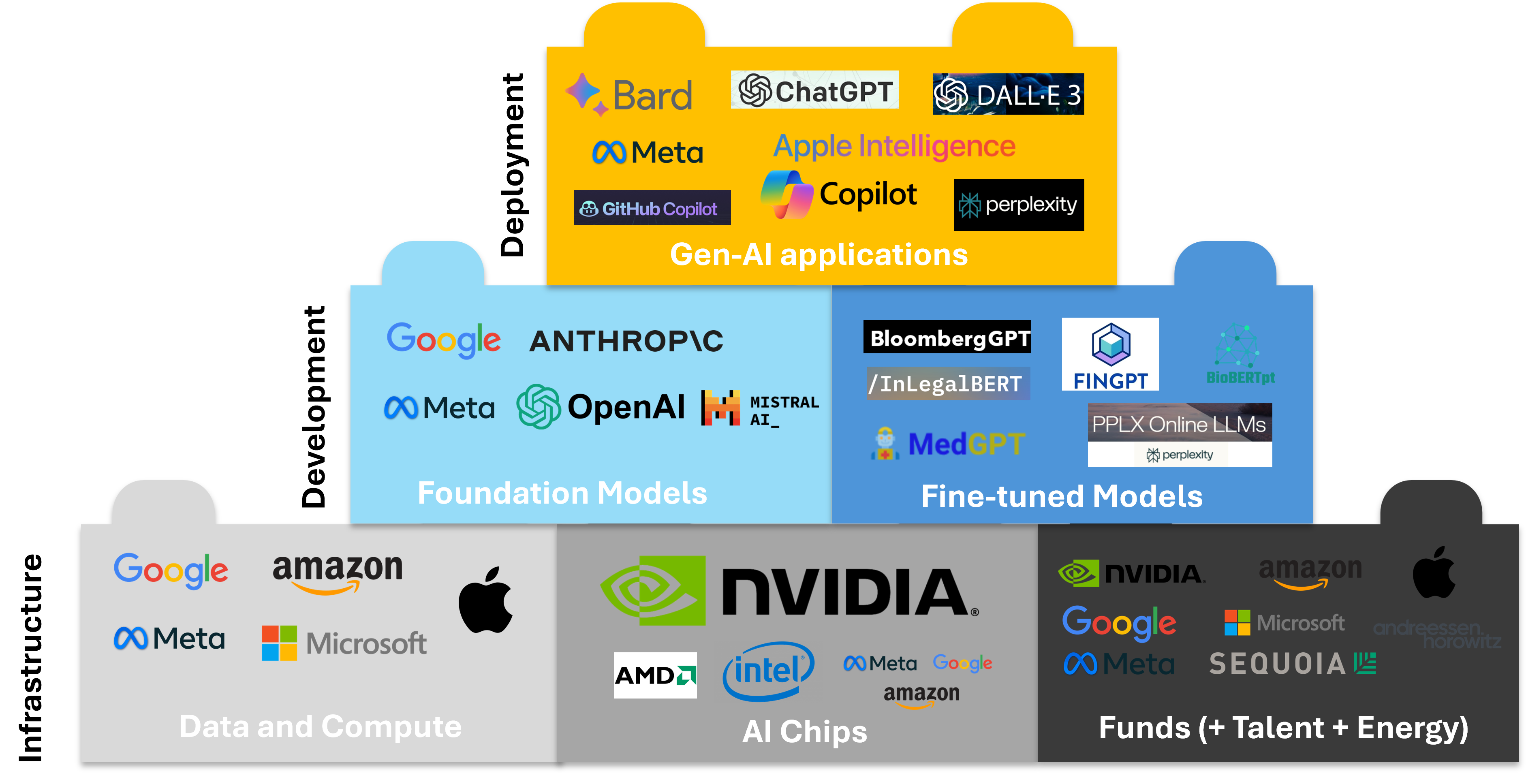

In contrast to the apps market, where frenemy dynamics have somewhat run their course, the GenAI market is still in its formative stages. While several new startups have benefited from investments, partnerships and cooperation from Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Apple and NVIDIA (collectively called “GAMMAN companies“), there is concern about the extent of influence these companies have. Are there early signs that similar frenemy dynamics are emerging? To answer this, we need to understand what the GenAI market looks like. While it is fast-evolving and technological developments are constantly reshaping market boundaries, the GenAI market can broadly be divided into three layers – Infrastructure, Development and Deployment.

- Companies that provide the inputs required to develop and train foundation models – data, computing power (through cloud computing), AI chips, talent, funds and energy – form the Infrastructure layer.

- The Development layer consists of firms like OpenAI and Anthropic that develop and fine-tune the AI models.

- Deployment encompasses the multiple ways in which applications powered by GenAI reach the end user, either through standalone interfaces (like ChatGPT) or integrations into existing applications (like Microsoft CoPilot). Some of these GenAI-enabled services also compete against services without a GenAI component (e.g. Bing Search with CoPilot versus traditional Google search).

Here is a snapshot of the building blocks of the GenAI market, described above.

Source: Author’s analysis of publicly available information

Drawing lessons from the experience of the apps market, what can we expect to see if there are frenemy dynamics emerging in the GenAI market?

Is there evidence of frenemy dynamics in the GenAI market?

At first glance, the emergence of frenemy dynamics is not that obvious. While NVIDIA is still the largest supplier of AI chips, competitors like Intel, AMD, Amazon, Microsoft and Google have released or announced the future release of their own AI chips. OpenAI is still considered the frontrunner in the development of AI models, but Anthropic, Google and Meta are closing the gap, by developing models that match or outperform the latest offerings from OpenAI. The number of AI models has been increasing and many developers allow the development of applications on top of their models through open access or closed APIs. AI models are becoming smarter and less computationally demanding, which reduces the scale of inputs required and the market power enjoyed by suppliers of those inputs.

However, a closer examination reveals a more concerning picture. The evidence available to us in forming this picture includes:

Source: Author’s analysis of the ec_submissions_dataset

Let us see what the evidence tells us about the indicators of frenemy dynamics.

Entrenched market power

The evidence indicates that the GAMMAN companies have entrenched market power in the Infrastructure and Development layers. While other companies like IBM, Salesforce and Intel are active in these layers and could also have such market power, this analysis has primarily focussed on the GAMMAN companies. In the Infrastructure layer, NVIDIA enjoys a near monopoly in the production of a crucial type of AI chips and its proprietary technology creates a “competitive moat” that prevents AI developers from switching to an alternative. Once a model has been trained on NVIDIA’s technology, it is very difficult to adapt the model to run on different hardware (see Anonymous, EC submissions). In the Development layer, the sheer scale of training inputs required and the increasing regulatory burdens for GenAI confer near insurmountable benefits to existing large players who have privileged access to their own cloud computing services, greater compliance resources and greater financial capacity to spend on AI models. Those with large customer bases also benefit from data feedback loops for finetuning their AI models, and find it easier to attract and retain talent. Therefore, NVIDIA and cloud computing companies (like Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform (GCP), and Amazon Web Services (AWS)) are likely to have significant market power. In the Deployment layer, there has not been a similar emergence of market power (see GitHub, EC submissions).

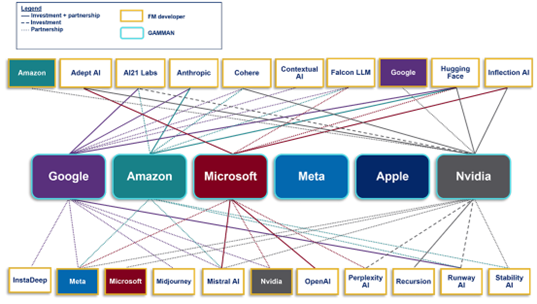

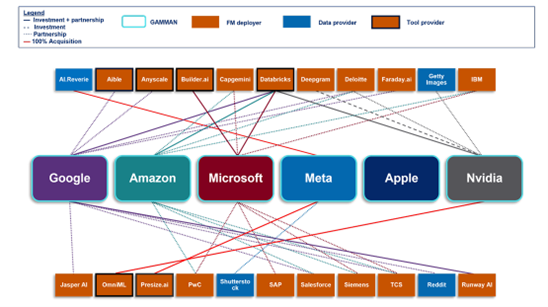

Further, GAMMAN companies are present across all layers of the GenAI market through their offerings, investment or partnerships. The CMA has identified 90+ partnerships (as visualised in the diagrams below) that GAMMAN companies have entered into with developers of AI models as well as deployers, data providers and providers of developer tools for those models.

Source: CMA Report AI Foundation Models (18 September 2023)

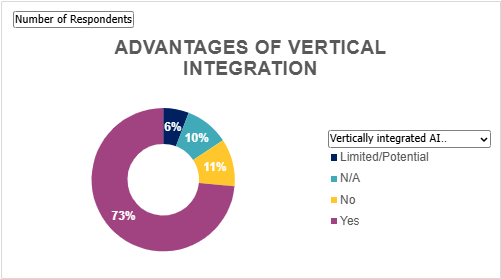

Although Apple is not included in this mapping, public sources indicate that it has invested close to $22.61 billion, in part on AI technologies and in 2023 alone, purchased at least 32 AI startups. The GAMMAN companies along with Salesforce, Oracle, IBM and Intel have venture capital funds that regularly invest in GenAI start-ups (see Microsoft, EC submissions). This trend has continued with Amazon investing additional $4 billion in Anthropic and NVIDIA investing in more than ten $100 million-plus funding rounds for A.I. startups in 2024. This aligns with the view from the market as per the EC submissions, where 73% of the respondents felt that vertically integrated companies enjoy an advantage over other players.

Source: Author’s analysis of the ec_submissions_dataset

Leveraging, exclusionary practices and killer acquisitions:

As Carugati has noted, authorities in South Korea, the Netherlands, Japan, France, the UK, the US and Spain are scrutinising the cloud computing sector, as they are concerned about issues arising from barriers to switching, data transfer fees, software licensing practices and interoperability. Similarly, France and US have been investigating NVIDIA’s practices in the AI chips market. There are already concerning signs that certain players are engaging in actions that may have an adverse effect on competition. For instance, in March 2023, Microsoft threatened to cut off access to its web index to firms that use it to compete with its own AI chatbots. There is also concern that large companies like Microsoft that operate at different layers of the market can engage in cross-subsidisation, where they make AI available across its ecosystem for a price that standalone services cannot compete with (see Alfaview, EC submissions).

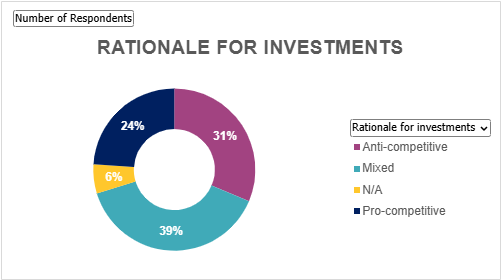

Several competition authorities have focussed especially on the partnerships between large technology companies and start-ups. As analysed by Copenhagen Economics, these partnerships are often the only way that start-ups can secure the computing power, external funding and distribution channels necessary to develop GenAI models. Since the larger partner has access to a key input or an important distribution channel, it may obtain favourable terms which could create competition concerns. The analysis of publicly available data also indicates that these partnerships often contain such terms, in relation to control, profit sharing, exclusivity and access to the underlying technology. For instance, Amazon’s latest investment in Anthropic was contingent on it being Anthropic’s primary training partner, primary cloud provider and supplier of AI chips. This is consistent with the EC submissions, where 70% of the respondents considered that partnerships with large players have an anti-competitive or mixed effect and are often entered into to secure their dominance in the market. For instance, these agreements can create a technical lock-in, where a cloud service provider partnering with an AI developer, may permit the use or deployment of the model only from its own infrastructure (see AFEP, EC submissions).

Source: Author’s analysis of the ec_submissions_dataset

Finally, acquisitions by GAMMAN companies are being scrutinized by competition authorities. NVIDIA’s acquisition of Run:ai is being investigated by the US Department of Justice and has been referred to the EC. In March 2024, by hiring key employees from Inflection AI, including its co-founders, and procuring a licensing deal to utilise Inflection IP, Microsoft effectively absorbed a significant portion of Inflection’s talent and expertise. While not a traditional merger, it has been investigated by the CMA alongside four other partnerships between GAMMAN companies and startups. As analysed by Herbert Smith Freehills, although none of the investigations progressed to an in-depth Phase 2 review, the seniority of the decision-makers indicates that these investigations are receiving high levels of attention within the CMA.

Intellectual capture:

While it is difficult to conclusively determine if there has been intellectual capture, the EC submissions indicate an interesting distribution among the responses. Among the minority of respondents (13) who answered that vertically integrated companies do not enjoy a competitive advantage:

- 1 (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation) is a think tank funded in part by Google and the Information Technology Industry Council (which represents large US technology companies);

- 1 (IVSZ) is an industry association that has conducted a study with Microsoft in the past; and

- 3 (InnovUp, Polish Confederation Lewiatan and SPCR) are industry associations that have word-for-word identical submissions to IVSZ.

- 2 (Ametic and ZCP) paraphrased the IVSZ’s submission but have kept the sub-headings unaltered.

Similarly, several other think tanks (like Global Antitrust Institute, International Center for Law and Economics, Open Data Institute, CCIA Europe etc.) which answered N/A to this question are funded by or have links with GAMMAN companies, and their responses in the EC Submissions are quite aligned. While this may not indicate intellectual capture, it shows that the perspectives and interests of the GAMMAN companies are overrepresented in the EC submissions. From this perspective, the majority viewpoint supporting the opposite conclusion appears even more credible.

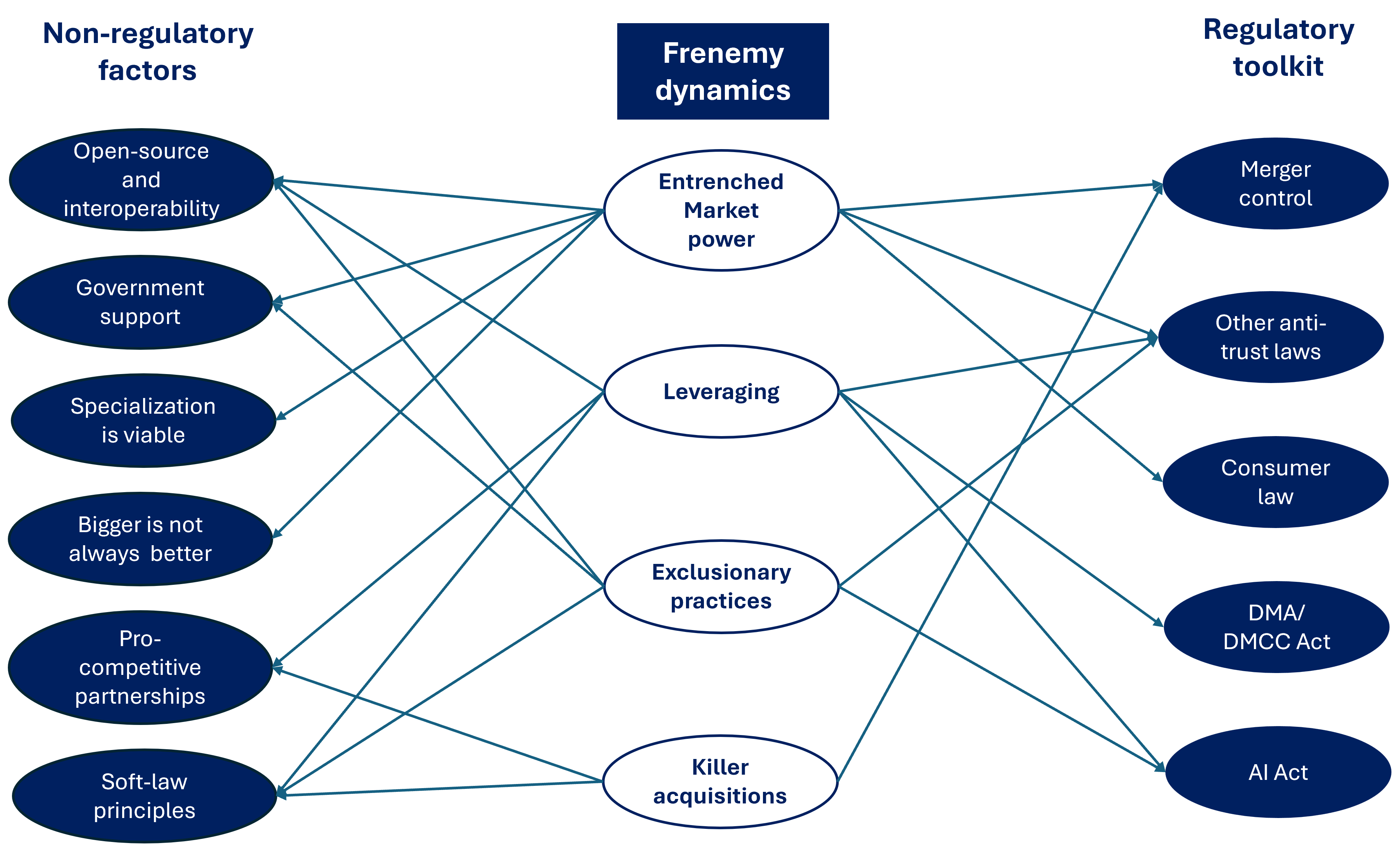

How can frenemy dynamics in the GenAI market be addressed?

Now that we have some evidence of frenemy dynamics in the GenAI market, how can these be addressed, especially considering developments in digital markets of the past? This includes a combination of the regulatory toolkit and non-regulatory factors.

Regulatory toolkit

Since competition authorities have encountered and dealt with frenemy dynamics before in other digital markets, some of their regulatory tools, including the regimes created for other digital markets, can be applied here.

Competition and consumer law: Some instances are directly covered by traditional competition and consumer law. For instance, leveraging conduct by dominant companies can be assessed under Article 102 of the Treaty of Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’) or its national equivalents. Existing competition law can also cater for lack of multi-homing or vertical integration practices (see Bauer, EC submissions). Acquisition by dominant firms of potential or actual competitors, including by hiring of key personnel (as happened in the Microsoft-Inflection case), could trigger merger inquiries. Finally, authorities can take recourse to consumer law principles to tackle what they see as problematic market behaviour in the AI space e.g. CMA’s work into online choice architecture.

Other regulatory regimes: Laws from other domains also address some of the competition law concerns in GenAI markets. While the Digital Markets Act (DMA) does not refer to GenAI and no AI model developers are currently designated as gatekeepers in relation to a core platform service, it is possible that the EC might apply the DMA to AI models, considering them a “gateway” between business users and consumers. In any event, several companies in the GenAI market have already been designated as gatekeepers under the DMA, and Martinez has analysed how existing obligations can be applied to functionalities of designated providers that rely on GenAI. The DMA could be applied in the AI space to require fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) access to key inputs, prohibit self-preferencing behaviour, supply the Commission with relevant information or to prevent the use of data to improve GenAI services without user consent under Article 5(2) (see Bauer, EC submissions). Provisions of the DMA can prompt compliance even without being directly binding. For instance, Microsoft bowed to pressure and voluntarily made a submission to the EC on its hiring of Inflection AI staff under Article 14 of the DMA, even though it was not required to do so.

The DMCC Act, the UK counterpart of the DMA, includes a new specific merger control threshold to capture potential killer acquisitions of startups that may not cross traditional turnover or share of supply thresholds. The procedural powers granted to supervisory agencies under the AI Act, such as the examination of evidence and access to relevant data and documents, might also grant the necessary oversight over some competition concerns.

Non-regulatory factors

Beyond the regulatory toolkit, there are several features of the GenAI market that make it different from digital markets of the past – these features have pro-competitive effects and might alleviate some of the risks flowing from frenemy dynamics. They must be considered alongside regulatory responses, as the pro-competitive benefits can be jeopardised if there is a chilling effect on investment due to over-regulation.

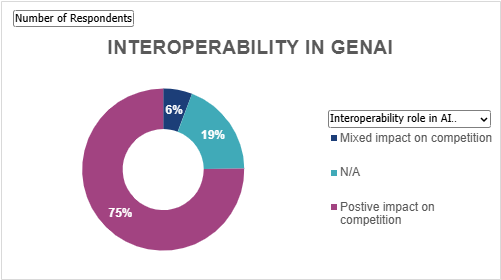

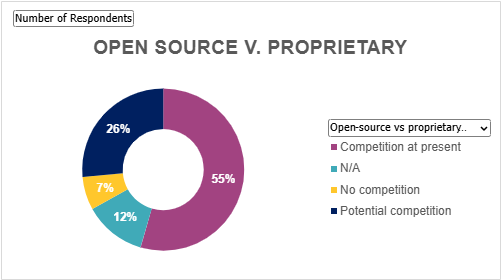

First, open-source alternatives and interoperability can reduce the risk that the market will tip towards a small number of closed offerings. As of 2024, 65.7% of foundational models are available on an open licence. While there are varying degrees of openness, as long as the weights of the model are publicly available such that they allow fine-tuning and application developers to freely build on them, such open-source models can act as a competitive constraint on players with closed models. Similarly, the availability of open-source datasets for training and finetuning models, which has exploded to over 250,000, and open-evaluation frameworks (like OpenAI eval) also have similar pro-competitive effects. Many components required to deliver a GenAI service (e.g. encoders, decoders, vector stores, orchestration layers etc.) are available open source, which lowers barriers to entry. Even when the final product is marketed as closed, 76% of the tech stack is composed of open source software code (see GitHub, EC submissions). It has been estimated that companies would have to spend $USD 8.8 trillion to rewrite code from scratch, if such open source components were not available (see GitHub, EC submissions). Interoperability allows customers to extract and port their data and communicate with other service providers, without being locked in. For instance, Adobe Photoshop allows customers to generate and edit images using Stable Diffusion and Dall-E 2 in lieu of its own product, Adobe Firefly (see Adobe, EC submissions). As per the EU submissions, 81% of respondents considered open-source can exert an actual or potential competitive restraint on proprietary systems. Moreover, 75% of respondents considered interoperability has a positive effect on competition in the GenAI market.

Source: Author’s analysis of the ec_submissions_dataset

Second, support from governments can help establish publicly funded alternatives that level the playing field. India Stack is a collection of open APIs and digital public goods that can help create a competitive environment by allowing new entrants to leverage existing infrastructure without significant investment. EU’s AI innovation package supports SMEs and startups, by providing access to EU supercomputers and high-quality datasets to train their models. Hungary has been developing its own large language models to foster local talent and innovation, reducing reliance on global tech giants.

Third, specialization is a viable business model, which diminishes the market power of certain players due to their sheer size and scale. Different firms may be able to compete effectively by using alternative sets of proprietary data to finetune models and focussing on specific domains like finance, law, medicine etc. Models are also differentiated based on task requirements. Finally, monolingual models (like Meta CamemBERT for French or the Hungarian LLM) perform better than multilingual ones and can provide more tailored solutions for local markets.

Fourth, increasing model size does not always translate to improved quality (see Digital Competition, EC submissions). There is a trend towards developing smaller models with fewer parameters to reduce financial, computing and environmental costs called small language models (SLMs). SLMs can be fine-tuned on specific datasets to achieve specific tasks better than LLMs with general domain data, like Meta Code Llama, which generates code. They can often equal the performance of larger models, such as Mistral which performs almost on par with the older OpenAI GPT-4 while being substantially “smaller” in its model weights. Some models, like Google Gemini Nano, can even run on a device and are more suitable for applications where low latency is preferable to a marginal increase in performance. Therefore, bigger is not always better.

Fifth, integration, cooperation and partnerships in the GenAI market play an important role in helping AI developers secure access to compute, data and funds. The prime example of this being OpenAI, which was assisted by its partnership with Microsoft. Such agreements can also have pro-competitive and efficiency benefits such as better integration of products, improved customisation etc. They can spur innovation by disrupting current markets and creating new ones. In some cases, the potential acquisitions can actually encourage innovation and competition, by providing a more predictable exit plan for startups to recoup initial investment, which incentivises them to launch new services that would otherwise be too risky to monetize (see ACT – The App Association, EC submissions).

Sixth, soft-law principles can also influence the behaviour of AI companies, who are aware of previous regulatory interventions in other markets and keen to avoid such actions in the GenAI market. For instance, the joint statement by authorities in EU, UK and US laid down three principles for protecting competition in the AI ecosystem – fair dealing, interoperability and choice. The CMA went one step further by spelling out the expected behaviour under these principles, alongside others like diversity, transparency and accountability. In the Microsoft/Mistral case, the CMA concluded that the partnership did not qualify for investigation but used the remainder of the decision to set out a framework around the assessment of material influence for AI partnerships. As Herbert Smith Freehills note, one possible justification for the CMA’s action could be to provide greater clarity for businesses and put them on notice about conduct that could rise to the threshold of intervention. Many of these principles are also reflected in the internal policies of companies like Microsoft and Meta (see Meta, EC submissions).

Source: Author’s analysis

However, not all risks to competition arising from frenemy dynamics are addressed by the regulatory and non-regulatory factors mentioned above.

Insufficiency of the existing regulatory toolkit: As Ezrachi and Stucke note, existing competition law does not necessarily cater for frenemy dynamics. Overly time-consuming behavioural enforcement remedies may not be sufficient for the fast-moving developments in the GenAI space. It may be difficult to accurately assess the market power of firms, due to the challenges of defining the relevant market(s), strong network effects and high barriers to entry, and the nascent and ever-changing GenAI market. The merger enforcement regime may not apply to AI business that have turnover or market shares well below the jurisdictional threshold, especially after the judgment in Illumina/Grail and the ongoing uncertainty about the treatment of below-jurisdiction mergers.

The protections under the DMA or DMCC Act may not apply if the relevant company or activity is not designated as such. Specifically, it is unlikely to address the risks where Generative AI is offered as a standalone service (see EBU, EC submissions). Therefore, some countries have been arguing for a market investigation style tool, which would allow them to look at, and intervene in, markets in a more holistic manner than currently possible in a behavioural or merger control framework. It is significant to note that in the EC submissions, around 66% of respondents felt that the existing legal antitrust concepts need to be adapted to suit the GenAI market. Even among the respondents who disagreed, some considered that traditional investigation methods and enforcement practices might need updating (see IBM and ITIF, EC submissions) and encouraged competition authorities to use its investigative tools to learn more about the GenAI market (see Microsoft, EC submissions).

Source: Author’s analysis of the ec_submissions_dataset

Complexity of non-regulatory factors: Non-regulatory factors do not always have the desired effect on frenemy dynamics. Open-source alternatives may not compete effectively with proprietary systems. There have been calls to exempt such systems from some of the rigorous documentation requirements under law, at least in the early stages, to equalize the playing field (see Booking.com, EC submissions). For several corporate use cases, there can difficulties in implementing open-source systems, and the heterogenous, non-traceable learning bases of open-source models can pose concerns from an intellectual property law standpoint (see AFEP, EC submissions). There is also no guarantee that after the significant implementation costs, these open-source models will be maintained or adequately protected against cybersecurity threats (see Elitmind Group, EC submissions). Despite the benefits of interoperability, mandating it (especially for early-stage startups) may do more harm than good – constraining innovation and increasing compliance costs (see ACT – The App Association, CETA and OpenAI, EC submissions). Finally, as Killick has analysed, it is not clear how innovation as a pro-competitive benefit can be balanced against potential harm to competition.

International fragmentation: Another complicating factor is that the risks from frenemy dynamics are likely to materialize ways that does not respect international boundaries. Unlike previous digital markets, companies in the GenAI market are more geographically distributed and less concentrated in the US (see Abraham Song, EC submissions). There might be a race to the bottom where countries try to attract the best AI companies and host the most advanced models. For instance, there is concern that early or disproportionate regulatory interventions might stifle competitiveness of geographical markets (see BDI, EC submissions). A recently proposal to exempt Mistral AI (France) and Aleph Alpha (German) from regulatory burdens might be prompted by a desire to achieve an industrial policy goal of promoting European firms. Moreover, different approaches by competition authorities around the world could make the legislative and regulatory backdrop hard to navigate, further exacerbating barriers to entry created by compliance burdens. Even under the DMA, Article 1(6.b) allows national competition rules to impose additional obligations on gatekeepers, which further creates the risk of fragmentation.

A potential way to resolve this is greater cooperation between authorities and joint studies in a forum like the European Competition Network (ECN) or International Competition Network (ICN) (see Digital Competition, EC submissions).

Where do we go from here?

The technologies underpinning the GenAI revolution are new and constantly evolving, and competition authorities must devote resources to grapple with these developments by improving their technical expertise and capabilities. However, as Vestager pointed out in a recent speech, the underlying human motives of players in the GenAI market – greed, benevolence, working for the public good, working for enrichment – are familiar to competition authorities. This is consistent with recent developments in the market: originally a nonprofit, OpenAI is now a for-profit corporation valued at $29 billion and is even considering a advertising-revenue model to reach its profitability goals.

So where do we go from here? Given the similarities in frenemy dynamics, it is worth revisiting what Ezrachi and Stucke said about digital markets in 2016 to see if they hold any lessons for the GenAI market:

“(t)hese technological developments will not necessarily improve our welfare. Much depends on how the companies employ the technologies and whether their incentives are aligned with our interests…(these) markets will not necessarily correct themselves.

[…]

The concerns are real, but so are the challenges for intervention. The anticompetitive effects are not always easy to see. Companies can be a step ahead in developing sophisticated strategies and technologies that distort the perceived competitive environment…Controversy may surround the timing of an intervention, its nature, and its extent.”

We need careful and measured intervention to safeguard consumer welfare and promote competitive market environments in the GenAI space. The perceived risk from frenemy dynamics must be balanced against creating further entry barriers or chilling the dynamism of GenAI markets due to overenforcement. The lessons from previous encounters with frenemy dynamics must be applied, while being mindful of how the GenAI market differs from digital markets of the past. What that looks like is not always clear. However, what is clear is that doing nothing is not an option.