Five Golden CAFC Patent Cases of 2023

“Patent prosecutors, particularly in the life sciences, should carefully consider what disclosure is needed to enable full claim scope without undue experimentation, to avoid a trial-and-error situation like in Baxalta and Amgen.”

As 2023 draws to a close, here’s a gift of five golden Federal Circuit patent cases! These decisions issued by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) significantly impact patent practitioners in several areas, including patent prosecution, litigation, and inter partes reviews (IPRs).

Why It’s Golden: This is the first CAFC case addressing how estoppel applies to grounds not presented in an IPR petition.

Background: After Ironburg sued Valve for patent infringement, Valve filed an IPR petition against the asserted patent. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) issued a final written decision holding various claims unpatentable. The district court granted Ironburg’s request for summary judgment that Valve is estopped from asserting (among other things) certain invalidity grounds not presented in Valve’s petition (grounds which Valve subsequently discovered). The IPR estoppel statute, 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2), states that when a final written decision issues as to a claim, the petitioner is precluded from subsequently asserting in district court or at the ITC that the claim is invalid on “any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.” Valve appealed.

CAFC Decision: The CAFC observed that its prior case law had not fully addressed the standards for determining what non-petitioned grounds are estopped. Looking to district court decisions and the statutory language, the CAFC held that estoppel applies to invalidity grounds that a skilled searcher conducting a diligent search reasonably could have been expected to discover, and further held that the burden of proving estoppel under that standard rests with the patentee.

Practice Tips: IPR petitioners should consider the standard set forth in this case, regarding what grounds not included in petitions might be subject to estoppel. Patent owners seeking to assert the affirmative defense of IPR estoppel should think about how they will meet their burden under this standard.

2. In re Cellect, LLC, 81 F.4th 1216 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2023)

Why It’s Golden: For the first time, the CAFC has addressed how patent term adjustment (PTA) interacts with obviousness-type double patenting (ODP).

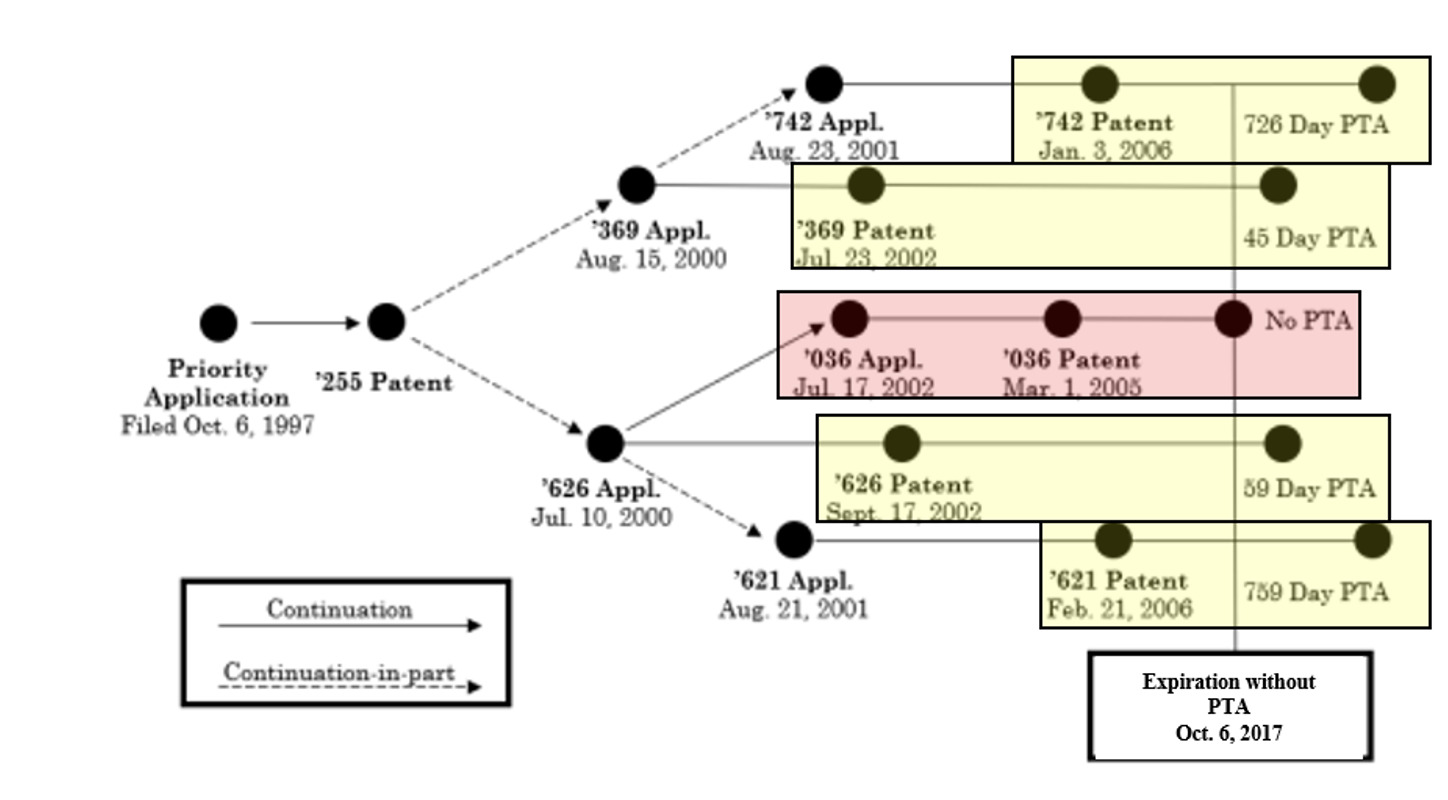

Background: Cellect sued Samsung for infringement of four patents in a family of patents that all claimed priority to a common priority application. Those four patents (highlighted below in yellow) received patent term adjustment (PTA) of different amounts for USPTO delay during prosecution, and another patent in the family (highlighted below in pink) did not receive PTA.

PTA is a mechanism, authorized under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b), for increasing patent term to compensate the patentee for USPTO delay during prosecution. Patent term extension (PTE) is a different mechanism (authorized under 35 U.S.C. § 156) for increasing patent term due to regulatory delays in product approval.

Samsung filed ex parte reexaminations on the four asserted patents. In each reexamination, the Examiner issued final ODP rejections, finding the claims patentably indistinct from an earlier-expiring family member’s claims. ODP is a judicially created doctrine that limits a first patent’s term by preventing the inventor from also obtaining a second, later-expiring patent with claims that are not patentably distinct. A terminal disclaimer may be filed to overcome an ODP rejection if (and only if) the first patent has not yet expired, by making the second patent expire at the same time as the first.

Cellect appealed to the PTAB, arguing that because ODP does not negate a statutory grant of PTE under CAFC case law, it also cannot negate PTA. Prior CAFC case law had only addressed PTE, and not PTA, in the ODP context. The PTAB disagreed with Cellect, and Cellect appealed to the CAFC.

CAFC Decision: Cellect argued that ODP determinations should be based on expiration dates before adding any PTA, so that all the patents would have the same expiration date (hence no ODP). Cellect argued that PTE-related case law, legislative intent, and statutory language all dictated that outcome. The CAFC disagreed. It noted there are different statutes for PTA and PTE, analyzed the PTA statute, and explained that Cellect’s interpretation would extend the overall patent term awarded to a single invention contrary to Congressional intent. Accordingly, the CAFC held that ODP for a patent having PTA must be based on the expiration date after PTA has been added, and affirmed the PTAB’s ODP determination. The CAFC noted that Cellect could no longer file terminal disclaimers (the usual solution for overcoming ODP) because all the patents had expired. Cellect has filed a petition for CAFC en banc rehearing of the panel’s decision, and that petition is currently pending.

Practice Tips: Practitioners should analyze expiration dates of patents in a family, and similarity of claims across family members, when some members have PTA. Terminal disclaimers can be filed during prosecution, even in the absence of an ODP rejection, and throughout the life of the patent, but not after the patent expires. Practitioners should weigh the downside of terminal disclaimers—reduced patent term—and the risk of a potential future ODP determination. Practitioners should also keep an eye out for resolution of Cellect’ en banc rehearing petition.

Why It’s Golden: This case involves Article III standing for appealing an IPR decision, which (if lacking) can doom the appeal.

Background: Allgenesis filed an IPR petition challenging Cloudbreak’s patent directed to treating an eye disease called pterygium. Cloudbreak had not sued Allgenesis for infringing the patent. The PTAB issued a final written decision in which the challenged claims survived, because the PTAB determined that (1) Allgenesis’ PCT application, which the petition relied upon, is not prior art since the challenged claims are entitled to an earlier priority date; and (2) Allgenesis did not prove obviousness. Allgenesis appealed both determinations.

CAFC Decision: Article III standing is required for an appeal at the CAFC (unlike IPRs). One of the requirements for Article III standing is an injury in fact. Allgenesis argued that it suffered an injury in fact based on (1) its potential infringement liability and (2) the PTAB’s priority determination. The CAFC disagreed and dismissed the appeal for lack of standing.

As to potential infringement liability, the CAFC analyzed a declaration from Allgenesis’ corporate officer. The declaration contained testimony about Allgenesis’ continued development of a product called nintedanib for the treatment of pterygium, and about Allgenesis’ expectation that Cloudbreak will seek to enforce its patent against any product brought to market. But the CAFC found that the declaration failed to identify any specific, concrete, imminent plans for Allgenesis to develop a nintedanib product that might implicate the claims challenged in the IPR.

The CAFC also rejected Allgenesis’ priority argument. Allgenesis’ argument was mainly that because Allgenesis’ PCT application and the claims challenged in the IPR both relate to nintedanib treatments for pterygium, the PTAB’s priority determination would have a preclusive effect on the scope of one of Allgenesis’ pending patent applications claiming priority to the PCT application. The CAFC noted that collateral estoppel would not attach to the priority determination, so if the examiner of the pending application were to reach the same priority determination, Allgenesis could challenge that in a separate appeal. Allgenesis also made other priority-related arguments that the CAFC rejected as being too vague and nonspecific.

Practice Tip: IPR petitioners not currently facing an assertion of patent infringement should carefully consider the issue of standing—and especially injury in fact—for any potential appeal in the future.

Why It’s Golden: This decision applies the Supreme Court’s recent Amgen decision and confirms that the Wands factors stay in place.

Background: Baxalta sued Genentech for infringement of a patent directed to treatment of a blood clotting disorder. Representative claim 1 recites:

“An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.”

Factors IX and IXa are enzymes involved in blood clotting. Using routine techniques, the inventors ran experiments to screen many candidate antibodies to find ones performing the claimed functions. The patent discloses the amino acid sequence of eleven antibodies that (as claimed) bind Factor IX/IXa and increase procoagulant activity of Factor IXa. The patent further discloses that a skilled artisan may use well-known techniques to transform those antibodies into different structural formats. The district court granted Genentech’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity of several claims (including claim 1) for lack of enablement. Baxalta appealed.

CAFC Decision: Baxalta argued that skilled artisans can make and identify new claimed antibodies, and thus obtain the full scope of claimed antibodies as required by the Supreme Court’s recent Amgen decision (Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. 594 (2023)), using the screening process disclosed in the specification. Baxalta further argued that such routine screening is not undue experimentation. The CAFC disagreed and affirmed the invalidity determination, finding the facts to be just like in Amgen—a case where the Supreme Court criticized disclosure of techniques that leave skilled artisans to engage in “painstaking experimentation” to see what works.

The CAFC explained that claim 1 covers all antibodies having the claimed functions, and there are millions of potential candidates, but the written description only discloses the sequence for eleven antibodies having those functions. The CAFC found that the written description simply directs skilled artisans to create a wide range of candidates and then screen each one to see which ones work. The CAFC noted that Amgen did not disturb prior enablement case law, and that the Wands factors for determining undue experimentation are still in place.

Practice Tip: Patent prosecutors, particularly in the life sciences, should carefully consider what disclosure is needed to enable full claim scope without undue experimentation, to avoid a trial-and-error situation like in Baxalta and Amgen. As suggested by the CAFC here, if there are many possible things (e.g., antibodies, genes, compounds, etc.) covered in the full claim scope, disclosure about some structural attribute common to the things that meet the claim, or about why certain screened things meet the claim and others do not, might help skilled artisans make predictions to obtain full claim scope without undue experimentation.

Why It’s Golden: This case provides a primer on the pre-AIA public use bar, which appears relatively infrequently in CAFC jurisprudence.

Background: Minerva sued Hologic and another defendant for infringement of a patent directed to surgical devices for reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing the asserted claims were anticipated by Minerva’s own device called “Aurora” under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment, and Minerva appealed.

Outcome: The CAFC affirmed, explaining that under pre-AIA § 102(b), the public use bar is triggered where, before the critical date, the invention is (1) in public use and (2) ready for patenting.

The “in public use” element is met if the invention was (a) publicly accessible or (b) commercially exploited by the inventor. The CAFC agreed with the district court’s public accessibility finding, since Minerva brought fifteen “full[y] functional” Aurora devices to a public commercial event—dubbed the “Super Bowl” of the industry—more than a year before the patent’s priority date. There, Minerva disclosed the Aurora device, without any confidentiality obligations, over several days at a booth, in meetings with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Minerva argued that its “mere display” of the device did not constitute public use, but the CAFC disagreed, noting that industry members scrutinized the device closely. The CAFC also explained that a device does not have to be physically handled by the public for there to be public use.

The “ready for patenting” element may be met by establishing (a) reduction to practice before the critical date or (b) enabling documentation describing the claimed invention. The CAFC agreed with the district court’s finding that both prongs were established.

Practice Tip: Litigators should be aware of the public use bar and can refer to the Minerva decision for details regarding its application.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: lenmdp

Image ID: 7601433