EU Tobacco Excise Tax Directive

Key findings

- An Update to the EU’s-Excise taxAn excise is a tax that is imposed on specific goods or activities. Excise taxes can be levied on a variety of goods and services, including cigarettes, alcohol, soda, gasoline and insurance premiums.

Directive that embraces harm reduction principles would save lives and provide a steady stream of revenue to support public health expenditures. - Taxing tobacco products according to the risks they pose to consumers encourages smokers to switch to less harmful products.

- One EU country, Sweden, has embraced alternative tobacco products, which has driven the nation’s smoking rate to the lowest level in the EU.

- The European Council and other Member States could learn from Sweden’s success and embrace harm reduction to reduce smoking rates across the EU.

- The EU plays an influential role in international tobacco taxation and could set an example for the rest of the world to effectively promote public health.

The EU Tobacco Excise TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

Directive & Current Tax Policies

After over a decade of not making any changes to the TED the EU will release an updated TED by 2025. A principled update to the TED, embracing harm reduction through new categories and rate differentials for less harmful products, will save lives and provide a steady stream of revenue for public health expenditures; poor choices in TED policy updates will result in more deaths, volatile revenue, and encourage the growth of illicit markets.[1]

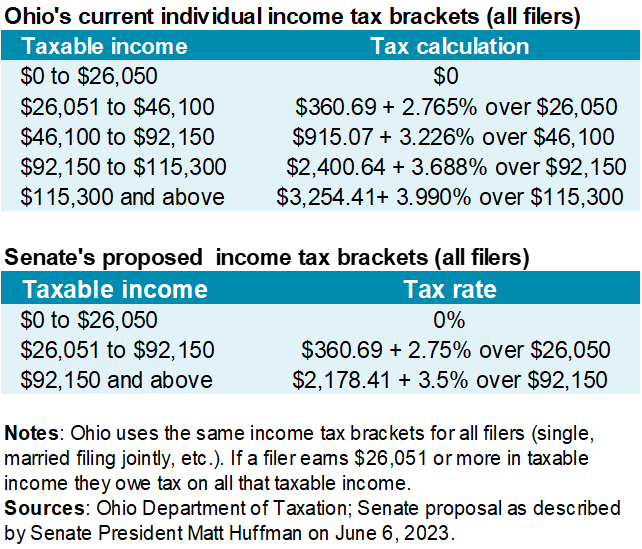

Currently, the TED requires a minimum excise duty on cigarettes and other tobacco products. The TED mandates both a specific ad quantum excise tax (a fixed euro amount per pack) and an ad valorem tax (an additional percentage of the average retail selling price) on cigarettes.

The current minimum tax rates are EUR1.80 tax per pack of 20 cigarettes and a minimum duty of 60 percent of the country’s weighted average retail price. The minimum duty does not have to be 60 percent if the country imposes a higher excise of at least EUR2.30 a pack. The TED sets minimum rates, but every country imposes taxes higher than these rates. These myriad taxes stack up to a significant burden on consumers–totaling more than 80 percent of the retail selling price on average in 2024, meaning the combined taxes increasedharmoni consumer prices of cigarettes by more than 450 percent in the EU on average.

Table 1. Average EU Cigarette Taxes on a Pack of 20 Cigarettes as of January 2025 [2]

Source: European Commission Taxation and Customs Union; authors’ calculations.

While the TED establishes a minimum tax rate, the harmonization efforts do not extend to any rate maximum. The result is that there are a wide variety of tax rates in the EU, as many Member States have taxes much higher than the minimum tax rate. With VAT added, the tax burden ranges from EUR2.54 in Bulgaria to EUR13.72 for Ireland. Germany has the lowest relative tax burden with total taxes making up 69.1 per cent of the country’s weighted-average price. The Netherlands has the highest relative tax burden with total taxes making up 110 per cent of the country’s weighted-average price. According to Article 8 (Subsection 2). of the Tobacco Tax Directive the weighted average price can be calculated from previous years. This allows tax shares to exceed 100 percent based on the lower prices. Taxes are always less than 100% of the current year’s price. These products include fine-cut smoking tobacco, cigars and cigarillos, and other smoking tobacco.

Table 2. Minimum EU Tax Rate on Other Tobacco Products

Source: European Union Tobacco Excise Directive.

Notably, the other tobacco products (OTP) covered by the TED are limited to combustible tobacco, which leaves out most innovative alternative tobacco products (ATPs).

The TED has three broad goals for the Commission: ensuring the “proper functioning of the internal market” via harmonization across Member States, ensuring a “high level of health protection,” and generating tax revenues.

“Proper functioning” of the EU’s internal market refers generally to avoiding distortions to competition between Member States to further the maintenance of an economic union. A minimum tax rate is set to prevent any one member state from undercutting others, which could also undermine efforts to protect health. Harmonization is also used to help reduce the prevalence of smuggling and illicit markets.

Taxes increase the price consumers must pay for tobacco, thereby incentivizing smokers to purchase fewer (legal) products. In the past, smokers were resistant to reducing their consumption in response tax-induced price hikes, so large taxes would have been necessary to meaningfully reduce consumption. This effect was largely due to a lack substitutes for nicotine consumption. However, with affordable alternative nicotine sources now available, smokers have demonstrated a willingness to move away from combustible cigarettes to ATPs.

Cigarette consumption is associated with harms to consumers and some bystanders, so a reduction in cigarette consumption would improve public health. The TED has other goals than improving public health. Revenue generation is one of them. The directive implicitly prioritizes competition in the internal markets and health protection over revenues. The maximum rates are not codified and each Member State is responsible for determining the rate, provided that they adhere to the tax rate ceiling. Tax Policies Have Trade-offs – The Economics of Tobacco Taxes

Tax policies have trade-offs. The higher the tax, however, the more likely it is that people will turn to the black market and illicit markets. Harmonization, health protection, and revenue generation are all undermined by the prevalence of smuggling, fraud, and illicit markets of tobacco products like cigarettes.

From a public finance perspective, cigarette taxes are also regressive and provide a volatile revenue stream attached to a shrinking

tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base can be inefficient and non-neutral. A broad tax base allows for lower tax rates and reduced administration costs.

[3]. These issues should raise concerns over further increases to the existing tax rates.

Cigarettes make an ideal product for illicit markets.

They are lightweight, easy to transport, legal to consume, and products can be sold for a fraction of the legal price simply through tax evasion. KPMG estimates 35.2 billion contraband and counterfeit cigarettes were consumed in EU Member States by 2023.

That is 8.3 percent of the total cigarettes consumed in those countries. These counterfeit and contraband cigarettes, if purchased legally, would have generated at least EUR11.6 billion in additional tax revenue.[4]Punitive taxation and enforcement alone will likely not be enough to adequately address the problem, let alone eliminate it. While enforcement plays an important role in combating illicit markets, designing a tax and regulatory regime that encourages participating in legal (and taxed) transactions is an even more important factor.

Similarly, draconian regulatory schemes and excessive taxation rates threaten to grant market share to an illicit market for ATPs just as they do for cigarettes. In Europe, there is a thriving illegal market for vaping devices, which are often smuggled in from China and Russia. Tobacco taxes disproportionately affect low-income consumers because cigarette taxes are regressive. Tobacco taxes disproportionately affect low-income consumers because cigarette taxes are regressive.

All excise taxes tend to be regressive to some degree, but cigarette taxes are the most regressive of the common excise taxes largely due to the increased prevalence of smoking among people with lower incomes.

From a public finance standpoint, excise taxes have particularly narrow tax bases, which contribute to their revenues tending to be particularly volatile. This makes them uniquely ill-suited to furnish general funds as the revenues are inherently unreliable.This effect is exacerbated for cigarette taxes by the decades-long trend of declining cigarette consumption. The prevalence of smoking has decreased steadily across most EU countries since at least 2006.

The tax base of cigarette taxes is ever shrinking, which means that even if revenue increases temporarily in response to a rate hike, the long-run trend will steadily decrease as fewer Europeans smoke.[5]Tobacco tax policy is complicated because combustible tobacco products are far from the only option to consume nicotine; innovation and development of ATPs have massively changed a market historically dominated by traditional cigarettes.[6]Harm Reduction and Alternative Tobacco Products

ATPs are products that enable the consumption of nicotine without the most harmful aspect of smoking: the inhalation of burning toxins. Nicotine is a chemical found in tobacco, but it is not a carcinogen. The research shows that nicotine does not cause lung or stroke cancers, or chronic obstructive respiratory disease (COPD), which are all commonly associated with smoking. By avoiding these other chemicals, consumers and bystanders will experience less harm. The ATPs are available in a variety of forms, with each having its own risk profile, nicotine delivery method, and consumer price profile. Heat-not-burn products, such as heated tobacco products, tobacco-free nicotine pouches and snus, are some of the most popular ATPs. HNB products can also be made with tobacco-free nicotine units. Vaping products (also known as e-cigarettes, ENDS or electronic cigarettes) use electronics to aerosolize nicotine-e-liquid, removing the tobacco from the process. This reduces harms associated with tobacco. Snuff or snus is a tobacco product that is cut or powdered and placed in the nose or mouth. This allows nicotine consumption without the harmful combustion. Nicotine pouches or modern oral nicotine are small pouches containing nicotine to be placed in the mouth and absorbed without the harm associated with chemical inhalation.

Each poses a varying degree of health risk, but those health risks are all considerably less than smoking. These noncombustible nicotine products and tobacco-free tobacco products are also significantly less harmful to consumers and passersby than combustible cigarette. The A The It Substituting ATPs for cigarettes has widely been found to be a useful tool for smoking cessation.[7]

Smoking cessation is notoriously challenging.[8] Embracing substitution for a less harmful nicotine consumption method is one possible resource for smokers wanting to quit. Nico Harm reduction through substitution is likely more effective at encouraging smoking cessation than punishment through taxation, as are direct monetary incentives.[9]

Some countries outside of the EU have already integrated harm reduction, to some degree, into their tobacco control regimes. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes less harmful products as modified risk tobacco products that receive a lower tax rate commensurate with their lower risk profiles.[10] The FDA began these classifications with Swedish-style snus products–popular in Sweden but outright prohibited almost everywhere else in the EU.

The UK’s Royal College of Physicians has concluded that the long-term health risks from vaping is “unlikely to exceed 5% of the harm from smoking tobacco” and emphasizes that “harm reduction has huge potential to prevent death and disability from tobacco use, and to hasten our progress to a tobacco-free society.”[11] Public Health England agrees that e-cigarettes are approximately 95 percent less harmful than smoking cigarettes.

In the EU, however, the TED fails to acknowledge many ATPs and thus precludes much harm reduction. In The Sweden This These Tax A more pragmatic tax policy that integrates harm reduction could provide a better balance between public health and revenue generation.

The best practices for sound tax treatment of ATPs involve simple, direct ad quantum taxes. Tax This This This rate can be levied as a reduction to the rate applied to cigarettes, commensurate with a specific product’s understood place on the risk continuum.

The risk continuum quantifies the relative overall risk of a product–accounting for the direct harm that the product causes to consumers and bystanders, the ease of substitution for combustible cigarettes, the ease of consumption of mass quantities, and the addictiveness of a product.[12]Using this framework, a spectrum of four categories of reduced-harm products can be delineated.

Table 3. Alternative Tobacco Product Tax Rates to Optimize Harm Reduction

Source: Tax Foundation, “How Should Alternative Tobacco Products Be Taxed?”

This categorical approach establishes a relatively easy way for Member States to embrace harm reduction policies to promote smoking cessation and more effectively promote public health. Assigning products to categories based on their risk ensures that safer products will suffer a lower tax rate, establishing price differentials that encourage consumers to choose less harmful alternatives to smoking.

Making a wider variety of less harmful products available to smokers saves lives, shrinks illicit markets, and allows governments to gradually transition from the shrinking tax base that is combustible cigarettes.

Policies in Practice[13]

The exclusion of most ATPs from the current TED has created a fragmented market that, in addition to the problems of compliance and international business distortions, has also created a series of case studies on different policy outcomes.[14]One country has far outperformed its EU peers in reducing smoking prevalence and avoiding preventable deaths from tobacco use: Sweden. No In The Since A A wide range of safer nicotine products, with a variety of strengths and flavours [15]

, is legally available both online and in stores, supported by advertising, which raises awareness and encourages uptake.”[16]Concurrent with the country’s consistently low smoking prevalence, Sweden consistently has among the lowest per capita cancer rates and tobacco-related deaths in the EU.

Embracing ATPs and their harm reduction capacity is clearly heavily contributory to Sweden’s uniquely low smoking rate.[17] A study of tobacco use in Sweden over 36 years showed a continuous decline in smoking rates coupled with a substantial rise in snus prevalence.[18]

Snus plays a clear role in Sweden’s uniquely low per capita tobacco mortality rates.[19]

According to Swedish Minister of Finance Mikael Damberg, taxes on tobacco and nicotine products “are already structured in such a way that products are generally taxed on the basis of hazard.”[20]

As a result, a wide array of smoking alternatives has become available and accepted in Sweden, resulting in monumental strides towards reducing harms from smoking and tobacco consumption.

In stark contrast to Sweden’s achievement 16 years ahead of the EU’s 2040 goal of reducing smoking rates below 5 percent, most other Member States are far behind on progress toward reducing smoking. Studies of Sweden relative to neighboring countries show that embracing harm reduction yields about an additional 0.4 percent per year to the rate of decline in smoking prevalence.

Instead, many EU Member States have chosen an opposite approach, suppressing ATPs and undermining their harm reduction potential.

Estonia, for example, has particularly stringent restrictions on ATPs.

The nation levies an excise tax on e-cigarette fluid (EUR0.20 per mL) and has banned flavored vape products since 2019. Advertising of these alternative products is prohibited, even for nicotine replacement therapies, and ATPs experience particularly low prevalence relative to the rest of the EU.

Not coincidentally, Estonia experiences a relatively high smoking rate of 25 percent, which has increased by 7 percent since 2020.

Belgium’s smoking rate is slightly lower than the EU average at 21 percent. This The country has since banned nicotine pouches and disposable vapes entirely, wholly precluding any harm reduction from the less harmful products.

Ireland set a target for becoming “smoke-free” by 2025, much like Sweden, but the country’s smoking rate is still 16 percent, down only 2 percent from 2020 despite having the bloc’s heaviest tax on cigarettes. This The Sweden The It The The Businesses Enabling accessible and affordable ATPs would undermine the market share of illicit markets, both for the ATPs themselves and for traditional cigarettes, by driving consumers into safer legal transactions.

The thriving global cigarette and tobacco product smuggling industry could be significantly undermined by a TED that effectively integrates innovative products, embraces harm reduction principles, and sets a shining example for the other countries of the world.

EU action is particularly important now, during a time of tense international relationships. EU Tax Taxing tobacco products in proportion to their associated harms would help incentivize consumers to switch to less harmful consumption methods.

Embracing simple, science-based harm reduction principles would assist the EU in reaching its goals of reducing smoking rates, avoiding millions of preventable deaths, and setting an example that the rest of the world could follow to do the same for themselves.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.[21]

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.[22]

Subscribe

References[sic] The Council of the European Union, “Council Directive 2011/64/EU,” June 21, 2011,

European Commission Taxation and Customs, “Taxes in Europe Database v4,” [23]

Craig A. Gallet and John A. List Adam Joel 27, 2022, [24] Tobacco Advisory Group, “Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction,” Royal College of Physicians, April 2016, and Jennifer Maki, “The incentives created by a harm reduction approach to smoking cessation: Snus and smoking in Sweden and Finland.”[25] Delon Human, Anders Milton, and Heino Stover, “Missing the Target.”[26]

Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction, “Smoking, vaping, HTP, NRT, and snus in Estonia,” Knowledge*Action*Change, 2024, [27] European Commission Special Eurobarometer 539, “Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and related products,” June, 2024,

Belga News Agency, “Total ban on nicotine pouches in Belgium from 1 October,” Sept. 27, 2023, and Sylvain Plazy and Mark Carlson, “Belgium will ban sales of disposable e-cigarettes in a first for the EU,” Associated Press, Dec. 29, 2024, [28] Ireland’s National Public Service Media, “New excise duty on vapes and EUR1 rise on 20 cigarettes,” Raidio Teilifis Eireann, Oct. 1, 2024, and Micheal Lehane, “Cabinet approves ban on sale of disposable vapes,” Raidio Teilifis Eirann, Sept. 11, 2024, [29]

Ali Anderson, “Czech Republic to ban flavoured vapes and hike tax,” Clearing the Air, Sept. 10, 2024, [30] Harriet Hadnum, “The Global Impact of GDPR: How Its Influenced Privacy Laws Worldwide,” GlobalAILaw, and Ampcus Cyber, “What is GDPR? A Complete Guide to GDPR Understanding & Compliance,” Feb. 14, 2025, [31]Share this article

Twitter[32]

LinkedIn[33]

Facebook [34]