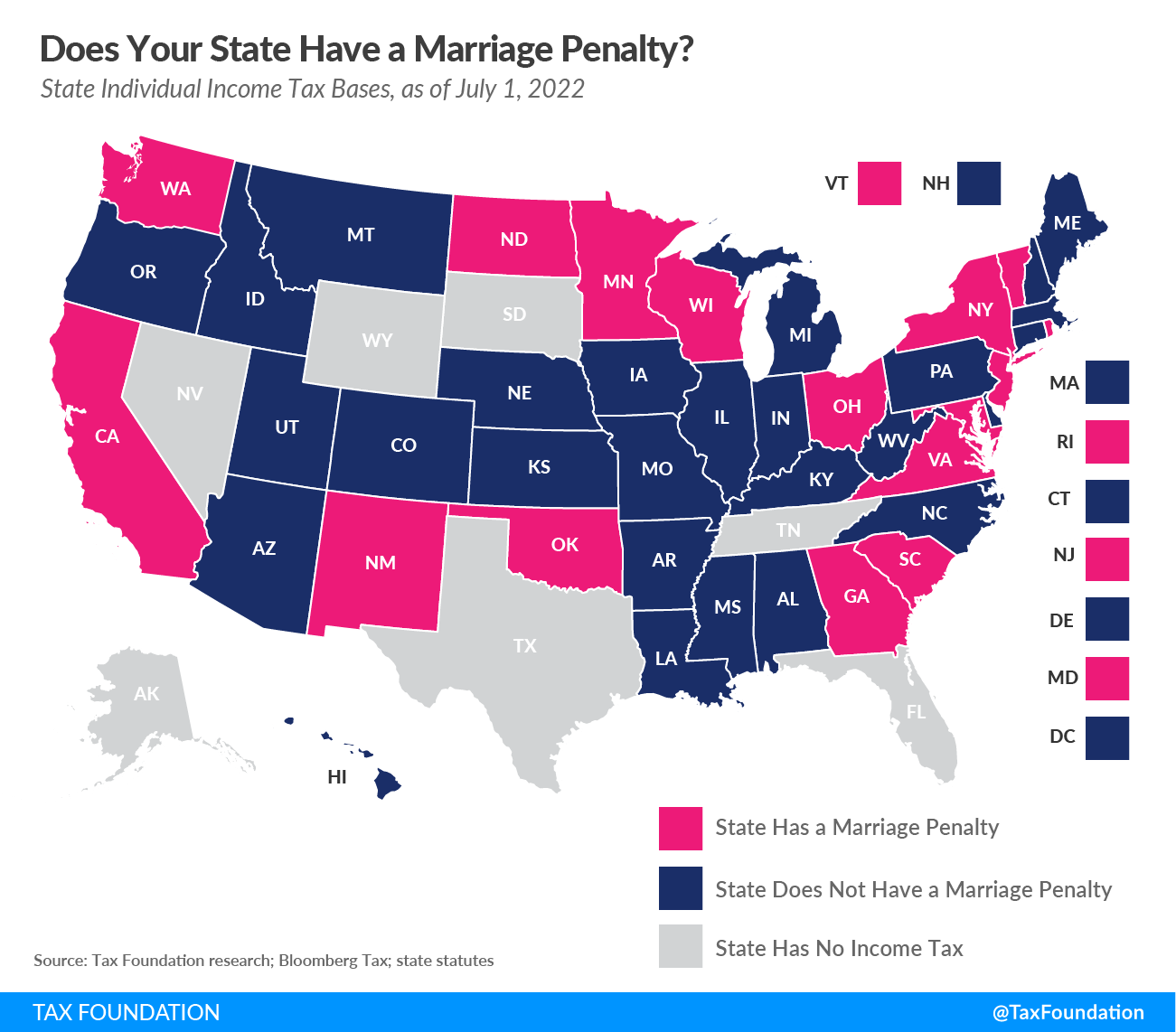

Does Your State Have a Marriage Penalty?

Today’s map zeroes in on states that have a “marriage penalty” in their individual income tax brackets. Under a graduated-rate income tax system, a taxpayer’s marginal income is subject to progressively higher tax rates. A marriage penalty or “marriage tax penalty” exists when a state’s income brackets for married taxpayers filing jointly are less than double the bracket widths that apply to single filers. In other words, married couples who file jointly under this scenario have a higher effective tax rate than they would if they filed as two single individuals with the same amount of combined income.

This non-neutral tax treatment is particularly harmful to owners of pass-through businesses, whose business income is taxed under the individual income tax system. Subsequently, under a state marriage penalty, married business owners are subject to higher effective tax rates on their business income than they would be otherwise.

Sixteen states have a marriage penalty in their individual income taxes. Fifteen of those are built into their bracket structure. Washington notably does not have a wage income tax but instead levies a capital gains tax with a $250,000 filing threshold. Because this threshold is not doubled for married filers, the state has an unconventional marriage penalty.

Seven additional states (Arkansas, Delaware, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, and West Virginia), as well as the District of Columbia, fail to double bracket widths but offset their marriage penalty in the bracket structure by allowing married taxpayers to file separately on the same return, avoiding loss of credits and exemptions. Ten states have a graduated-rate income tax but double their brackets to avoid a state marriage penalty: Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Nebraska, and Oregon.

The ability to file separately on the same return is important in states that do not double bracket widths, and so is the ability to do so even if the couple files jointly for federal purposes. While married couples have the option of filing separately—though some states only allow this if it is also done on their federal forms—this normally creates a disadvantage. It either disallows or reduces the value of deductions and credits available to the family jointly, which is also a form of state marriage penalty. Filing separately on the same return eliminates this problem, but is slightly more complex than doubling tax brackets for joint filers so that there is no penalty for filing jointly.

![[Event] Keeping Your Online Contests & Sweepstakes Legal – September 21st, Phoenix, AZ | Lewis Roca [Event] Keeping Your Online Contests & Sweepstakes Legal – September 21st, Phoenix, AZ | Lewis Roca](http://jdsupra-static.s3.amazonaws.com/authors/619bd413d2fab.200w.jpg?rand=62fadab4ddb41)