Divided court allows veteran to sue state-agency employer for violating his federal rights

OPINION ANALYSIS

on Jun 29, 2022

at 6:26 pm

In Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety, a five-justice majority on Wednesday allowed a military veteran’s lawsuit against his former state-agency employer to go forward, rejecting the state’s argument that it was shielded by sovereign immunity.

Le Roy Torres was working as a Texas state trooper when he was called to active duty in the U.S. Army Reserves. He served in Iraq and was honorably discharged, but his lungs were damaged by the burn pits that the military used to dispose of toxic waste. On his return, his injuries made him unable to perform all the duties of a state trooper, and he requested to be assigned to a comparable job in the Department of Public Safety. The department allegedly refused to accommodate him.

Torres therefore sued the department in a Texas state court, alleging that the department had violated his rights under the federal Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994. USERRA requires employers, including both state and private employers, to rehire employees into the same job after their service in the military. If injuries incurred during military service make the employee unable to perform the job, the employer must place the person in a position “that provides similar status and pay.”

The department moved to dismiss the suit on the ground that, as a state agency, it was immune from suit under the federal constitutional doctrine of state sovereign immunity. A Texas court of appeals agreed.

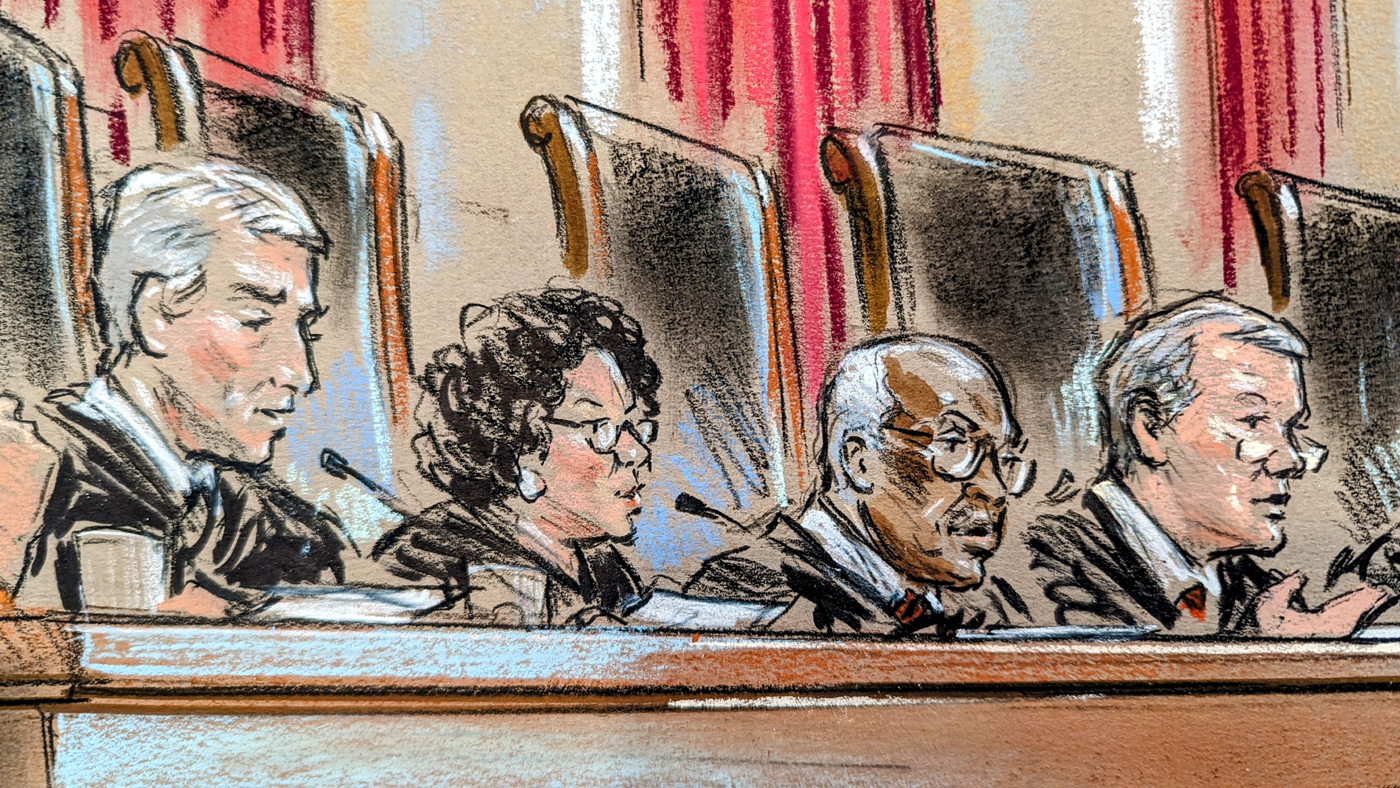

In an opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer — perhaps his last opinion as a justice – the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the states had waived their sovereign immunity to suits under USERRA. The court relied on two earlier cases, Central Virginia Community College v. Katz and PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey. Katz involved bankruptcy proceedings, and PennEast involved eminent domain proceedings. In both cases, the court held that by ratifying the Constitution, including the bankruptcy clause and the federal power of eminent domain, states had necessarily ceded their immunity as part of “the plan of the [Constitutional] Convention,” or in other words, as part of “the structure of the original Constitutional itself.”

USERRA was enacted under Congress’ war powers, which are scattered in various clauses in Article I of the Constitution. So the question before the court in Torres was whether the waiver of state sovereign immunity is similarly a structurally necessary component of Congress’ war powers. Is that power, Breyer asked, quoting PennEast, “complete in itself” so that “the States consented to the exercise of the power – in its entirety – in the plan of the Convention”?

In answering affirmatively, the majority opinion pointed to the “Constitution’s text, its history, and [the] Court’s precedents.” The text suggests “a complete delegation of authority to the Federal Government to provide for the common defense,” including divesting the states of authority over war and defense. The court cited numerous historical sources in support of its conclusion that preventing state interference with federal war powers – which nearly lost the war of independence – was a major impetus for the adoption of the Constitution. And “an unbroken line of precedents” going back to 1872 demonstrates that “Congress may legislate at the expense of traditional state sovereignty to raise and support the Armed Forces.”

Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, joined by Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett. The dissent argued, first, that Congress had not clearly authorized private suits against states under USERRA. (The majority responded by quoting three different provisions of USERRA: one that speaks of “Enforcement of rights with respect to a State or private employer”; another that provides that USERRA “supersedes any State law … that reduces, limits, or eliminates in any manner any right or benefit provided by this chapter”; and a third that authorizes suit “in a State court of competent jurisdiction.”)

More substantively, Thomas took issue with the majority’s view of history and precedent, especially on the question of whether states retained immunity in state (rather than federal) courts.

Much of the dispute revolved around language in the 1999 case of Alden v. Maine, which held that states were immune from suits in state court by private individuals seeking to enforce the federal Fair Labor Standards Act. The dissent relied on a quotation from Alden that “the powers delegated to Congress under Article I of the United States Constitution do not include the power to subject nonconsenting States to private suits for damages in state courts.” The majority responded with its own quotation from Alden: “In exercising its Article I powers Congress may subject the States to private suits in their own courts … if there is compelling evidence that the States were required to surrender this power to Congress pursuant to Constitutional design.”

Interestingly, the majority opinion in Alden was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, for whom both Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh clerked – and in Torres, they disagreed about the meaning of Alden, with Kavanaugh joining the majority and Gorsuch joining the dissent.

After all the sparring about history, structure, and precedent, the case comes down to a basic difference of opinion about the relationship between the federal government and the states. The dissent finds it “uniquely offensive to the States’ dignity” for the federal government to force state courts to enforce federal law. The majority believes that allowing Texas to claim immunity in this case “would permit States to thwart national military readiness,” and that “the power to wage war is the power to wage war successfully.”

Justice William Brennan once called the jurisprudence of sovereign immunity “a crazy quilt.” Justice Elena Kagan’s concurrence in Torres notes that the decisions in the area “have not followed a straight line.” And Thomas calls one aspect of that jurisprudence “murky.” Unfortunately, while this case is an important win for returning veterans, it does nothing to clean up the mess that the court has made of sovereign immunity doctrines.