District Court Rules PureCircle Steviol Glycoside Patents Invalid | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

On May 23rd, U.S. District Court Judge James V. Selna of the Central District of California granted summary judgement to Defendant Sweegen, Inc. on its motion that Plaintiff Pure Circle USA Inc.’s claims in suit were invalid for reciting patent ineligible subject matter and for failing to satisfy the written description and enablement requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a), in PureCircle USA Inc. v. SweeGen, Inc. Neither judgment was surprising in the current patent environment, but the District Court’s reasoning is illustrative of the current state of U.S. patent law.

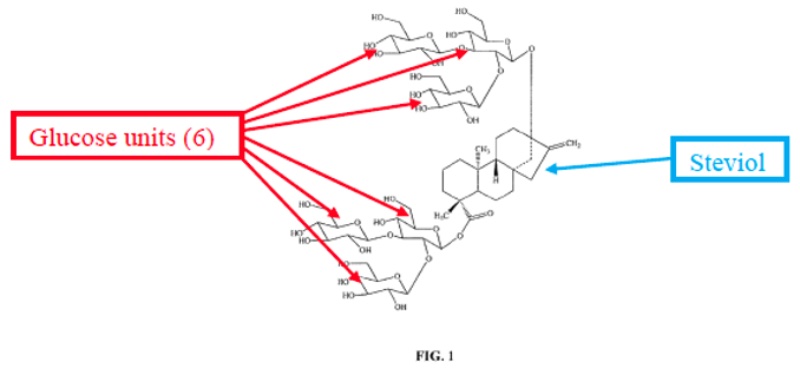

The suit involved methods for making particular glucosylated forms of the natural sweetener steviol obtained from the Stevia rebaudiana plant. The plant produces a variety of rebaudioside variants having various levels of glycosylation; the most predominant of these in the plant is termed “RebA” but this is not the most commercially valuable form. That form, termed variably “RebX” and “RebM” contains six glucose residues on the steviol core, illustrated in the opinion by this diagram:

(As will become evident from the claims, there are several intermediate glycosylated rebaudioside derivatives, termed RebB, RebC, RebD, etc.) The opinion sets forth that RebM is preferred due to its sweetness but that it only exists as “less than about 0.1% by weight of the total steviol glycoside content . . . in the natural stevia plant.”

PureCircle asserted all claims in U.S. Patent Nos. 9,243,273 (claims 1-14) and 10,485,257 (claims 1-7), and Sweegen moved for summary judgment that the ‘257 patent and ‘257 patent were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and § 112(a); the opinion set forth these claims as representative:

Claim 1 of the ‘257 patent:

1. A method for adding at least one glucose unit to a steviol glycoside substrate to provide a target steviol glycoside, comprising contacting the steviol glycoside substrate with a recombinant biocatalyst protein enzyme comprising UDP-glucosyltransferase, wherein the target steviol glycoside is Rebaudioside X.

Claim 1 of the ‘273 patent:

1. A method for making Rebaudioside X comprising a step of converting Rebaudioside D to Rebaudioside X using a UDP-glucosyltransferase, wherein the conversion of Rebaudioside D to Rebaudioside X is at least about 50% complete.

As stated in the opinion, “the method of the Asserted Patents makes Reb M by using UGT enzymes to add sugar units to a steviol glycoside with less than six sugar units until it has six, thereby converting it to Reb M,” wherein the UGT-glucosyltransferase enzymes used in the claimed methods are produced recombinantly in yeast cells.

The District Court granted PureCircle’s motion that Sweegen’s commercial product, Bestevia Reb M, infringed claims 1-7 of the ‘257 patent, which Sweegen did not dispute “to the extent that the claims are valid.” With regard to invalidity, Sweegen contended that the product of the claims was naturally occurring and that the method for making them merely replicated what occurs natively in the stevia plant. Accordingly, Sweegen maintained, the claims were invalid for being direct to laws of nature under the Supreme Court’s subject matter eligibility jurisprudence, which the District Court recognized to include Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2350 (2014); Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576, 577 (2013); Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 89 (2012); and Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 185 (1981). In addition, Sweegen asserted that the claims lacked an inventive concept base on five distinctions asserted in response by PureCircle:

1) the use of “recombinant” UGT enzymes in Claims 1-7 of the ‘257 Patent;

2) the use of “host microorganisms” to “express” the UGT enzymes in Claims 6-7 of the ‘257 Patent and Claims 12-13 of the ‘273 Patent;

3) the purity percentages for Reb M in Claims 3-5 of the ‘257 Patent and Claims 4-6 of the ‘273 Patent;

4) the conversion percentages of Reb D to Reb M in Claims 1 and 7-11 of the ‘273 Patent; and

5) the use of the UGT76G1 UGT enzyme in Claim 14 of the ‘273 Patent.

For the first two of these, Sweegen contended that the structure and function of the UDP-glucosyltransferases recited in the claims were identical to these enzymes as they exist in nature and did not recite “any non-natural role the enzyme plays in the claimed process” (which is a frequent source of invalidating comparison for any naturally occurring compound, insofar as changing the structure and/or function reduces or eliminates the desired biological activity). Regarding the third and fourth allegations of subject matter eligibility, Sweegen argued that the asserted claims contained no “steps or methods for achieving the claimed purity or completion percentages” (although this argument appears more fitting for a non-enablement or indefiniteness arguments). Finally, as to the fifth allegation, Sweegen argued that the disclosed enzyme, termed UGT76G1 was also naturally occurring.

PureCircle argued that the preparation methods did not occur in nature, with regard to taking an isolated RebA preparation and using a recombinant UDP-glucosyltransferase, analogizing these claims to the claims found patent-eligible in Rapid Litig. Mgmt Ltd. v. CellzDirect, Inc., 827 F.3d 1042, 1047 (Fed. Cir. 2016), and Illumina, Inc. v. Ariosa Diagnostics, 967 F.3d 1319, 1325-29 (Fed. Cir. 2020). PureCircle also pointed out that, in nature, the plant contains enzymes that deglucosylate steviol glycosides, thus making impossible production of RebM in quantities achieved using the claimed methods.

Sweegen countered by arguing that claims reciting man-made elements can be ineligible under Federal Circuit precedent, citing Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC, 915 F.3d 743, 750, 753-54 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. v. CEPHEID, 905 F.3d 1363, 1371-73 (Fed. Cir. 2018); Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371, 1373-74, 1376-77 (Fed. Cir. 2015), and further that the recited enzymes are “structurally and functionally identical to the naturally occurring UGT enzymes” and accordingly do not overcome patent-ineligibility of the asserted claims. Moreover, Sweegen argued that the purity and percentage of conversion to RebM do not in themselves change the “underlying natural process[es].” Finally, Sweegen argued that “methods of preparation” are not per se patent-eligible under the cited precedent.

The District Court agreed with Sweegen, finding claims 1-5 of the ‘257 patent and claims 1-11 and 14 of the ‘273 patent invalid for reciting patent-ineligible subject matter. According to the Court, the claims were directed to the natural law of converting rebaudiosides, and specifically RebD, into RebM. In the Court’s view, “there is no dispute that the conversion of steviol glycosides and Reb D to Reb M using UGT enzymes is a natural process.” The Court found this characterization to be supported by disclosure in the specification, which was expressed as disclosing a “biocatalytic process,” defined as “the use of natural catalysts, such as protein enzymes, to perform chemical transformations on organic compounds” (emphasis added). The Court relied on Athena for the proposition that “[s]ynthetically-created chemical compositions that are structurally and functionally identical to their naturally-occurring counterparts . . . are not patent eligible” and the admission in the specification that the recombinant enzymes were structurally and functionally “identical” to the naturally occurring enzymes. The District Court rejected the distinction PureCircle attempted to draw for “method of preparation” claims analogous to CellzDirect and expressly with regard to any suggestion that such claims are per se patent eligible, as being inconsistent with precedent particularly the Supreme Court’s rationale in Alice.

The claims of the ‘257 patent not invalidated on Section 101 grounds recited:

6. The method of claim 1, wherein the UDP-glucosyltransferase is expressed in a host microorganism.

7. The method of claim 6, wherein the host microorganism is selected from the group consisting of: Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces species, Aspergillus species, and Pisehia species.

And the claim of the ‘273 patent not invalidated on Section 101 grounds recited:

13. The method of claim 12, wherein the UDP-glucosyltransferase host microorganism is selected from the group consisting of: Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces species, Aspergillus species, and Pischia species.

The District Court recognizing these recited limitations as providing “something more” than the natural law as required under Supreme Court and Federal Circuit precedent, that something being in this case “a particular step performed by a human for achieving a particular result,” which the Court finds “takes those claims beyond the natural law itself.”

Turning to Sweegen’s motion for an invalidity finding on written description grounds, the District Court agreed with Sweegen that the recited claim element “UDP-glucosyltransferase” is a “broad, functionally-defined genus” and thus can embrace “not just naturally occurring UDP-glucosyltransferases, but ‘any’ UDP-glucosyltransferase mutant, fusion, and UDP-glucosyltransferase known or discovered after the patents’ . . . filing date” (estimated by Sweegen to encompass a trillion (1012), molecules, “a limitless number,” citing Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., 10 F.4th 1330, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2021)). The District Court also agreed with Sweegen that the specification does not recite a “a representative number of species or identify any common structural features for UGT enzymes” and that the sequence similarities between different UDP-glucosyltransferase were not correlated with enzymatic activity. In evidence was a comparison between 12 UGT enzymes wherein only 4 had shown an enzymatic activity that added glucose to steviol glycoside molecules. PureCircle countered this evidence by asserting that the term “”UDP-glucosyltransferase” is structural because, inter alia, there are other UGT enzymes that do not add glucose residues to rebaudiosides and that the Court’s claim construction limits the scope of the claims to those UGT enzymes that do transfer glucose moieties into rebaudiosides as disclosed and claimed. Finally, PureCircle argued that there are disputed material facts that preclude summary judgment, including that the term “UDP-glucosyltransferases” was itself structural and the structure of functional UGT enzymes had been determined by crystallographic comparisons (unfortunately for PureCircle, the District Court found that none of these crystallographically determined common structural features were disclosed in the specification). Sweegen countered that the specification did not provide (express) written description support for “every” UGT enzyme capable of converting inter alia RebD to RebM (which was the construction the Court gave to the claim element “UDP-glucosyltransferase”). In addition, Sweegen asserted that neither of the specifications disclosed structural features common to members of the genus of UDP-glucosyltransferases.

The District Court considered the issue to be whether the genus of UDP-glucosyltransferases was defined (and described) structurally or functionally and, deciding it was the latter, found that the claims did not provide adequate written description support. This determination was supported by the stipulated meaning of the term, i.e., “[a] type of enzyme that is capable of transferring a glucose unit from a uridine diphosphate glucose molecule to a steviol glycoside molecule.” Accordingly, the fact that these claims reciting this limitation were “original” claims they were not entitled to a presumption of adequate written description support. Under these circumstances, the Court held, precedent requires a showing that “the applicant has invented species sufficient to support a claim to the functionally-defined genus,” citing Juno, or “structural features common to the members of the genus so that one of skill in the art can ‘visualize or recognize’ the members of the genus,” citing Ariad Pharma. Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2010). The opinion states that there is no dispute between the parties that the specification does not expressly disclose “structural features common to all UGT enzymes” having the recited function; in fact only 4 UGT enzymes are disclosed (UGT76G1, UGT91D2, UGT91D2e, and UGT91D11) and the specification further states that “the particular UDP-glucosyltransferase used in each reaction can either be the same or different, depending on the particular site on the steviol glycoside substrate where glucose is to be added.” Amino acid sequence comparisons, which had been sufficient to overcome a written description rejection before the Patent Office were not persuasive before the Court, based on an understanding that “[a]n enzyme’s amino acid sequence does not necessarily predict the enzyme’s activity (or functionality) and, therefore, testing is always required to determine the enzyme’s activity (or functionality),” from which the Court concluded that “two enzymes with the similar sequences can have different functions and two enzymes with very different sequences can have the same function” (which, to be candid overstates what is a relatively weak biological rule of thumb). But here, the Court found that a comparison of two of the disclosed UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGT76G1 and UGT91D2) did not disclose common structural features sufficient to satisfy the requirement for an adequate written description. Finally, the District Court found that as of the filing date common structural features between different UDP-glucosyltransferases were not known in the art (and what features that were known were not universally associated with UDP-glucosyltransferase function). Accordingly, the District Court granted Sweegen’s motion that all asserted claims were invalid for failure to satisfy the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a).

The Court dismissed as moot a third ground of invalidity asserted by Sweegen, sounding in non-enablement. However, in view of the District Court’s rationale in its written description determination, and the recent trend at the Federal Circuit in applying the enablement standard in chemical, pharma, and biotechnology cases (see, e.g., Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi and Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Gilead Sciences Inc.) it is unlikely that PureCircle would have received any different outcome if the Court had considered this ground on the merits.

While the District Court’s decision is likely to be followed by an appeal to the Federal Circuit, PureCircle should expect an uphill battle. On the written description issue, as a question of fact the District Court is entitled to “clear error” deference which should prove difficult to overcome in view of the reasoning based on evidence cited in the opinion. And no patentee having had their claims invalidated under Section 101 has had any reason to be sanguine on appeal for the past ten years (although the recent Solicitor General’s amicus brief recommending the Supreme Court revisit the subject matter eligibility issue in Am. Axle & Mfg., Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC at least raises the possibility that there may be (perhaps just faint) hope for the standard to be reconsidered).