Debt Limit Deadline and Growing National Debt Demand Action

Congress has until early June to raise the debt limit and avoid a default on the nation’s debt, according to new estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Treasury Department. But Washington currently remains at an impasse, with major disagreements on whether a debt limit fix should be “clean” (i.e., no strings attached) or should include measures to reduce projected federal budget deficits. Acting swiftly to address the debt limit is imperative to avoid a real or perceived default. But so too is finding a fiscal solution to the nation’s growing debt. This blog post is the first in a series to explore the issues and potential solutions for growing deficits and debt.

The debt limit and projected federal budget deficits are distinct but related issues. The nation’s debt reflects the accumulation of past budget deficits—spending promises that have already been made and must be paid for. Congress limits the amount of debt that the Treasury can issue to pay those obligations, and the Treasury hit that nearly $31.4 trillion limit in January. It has since relied on cash balances and extraordinary measures to manage the debt in the interim, but that is about to run dry.

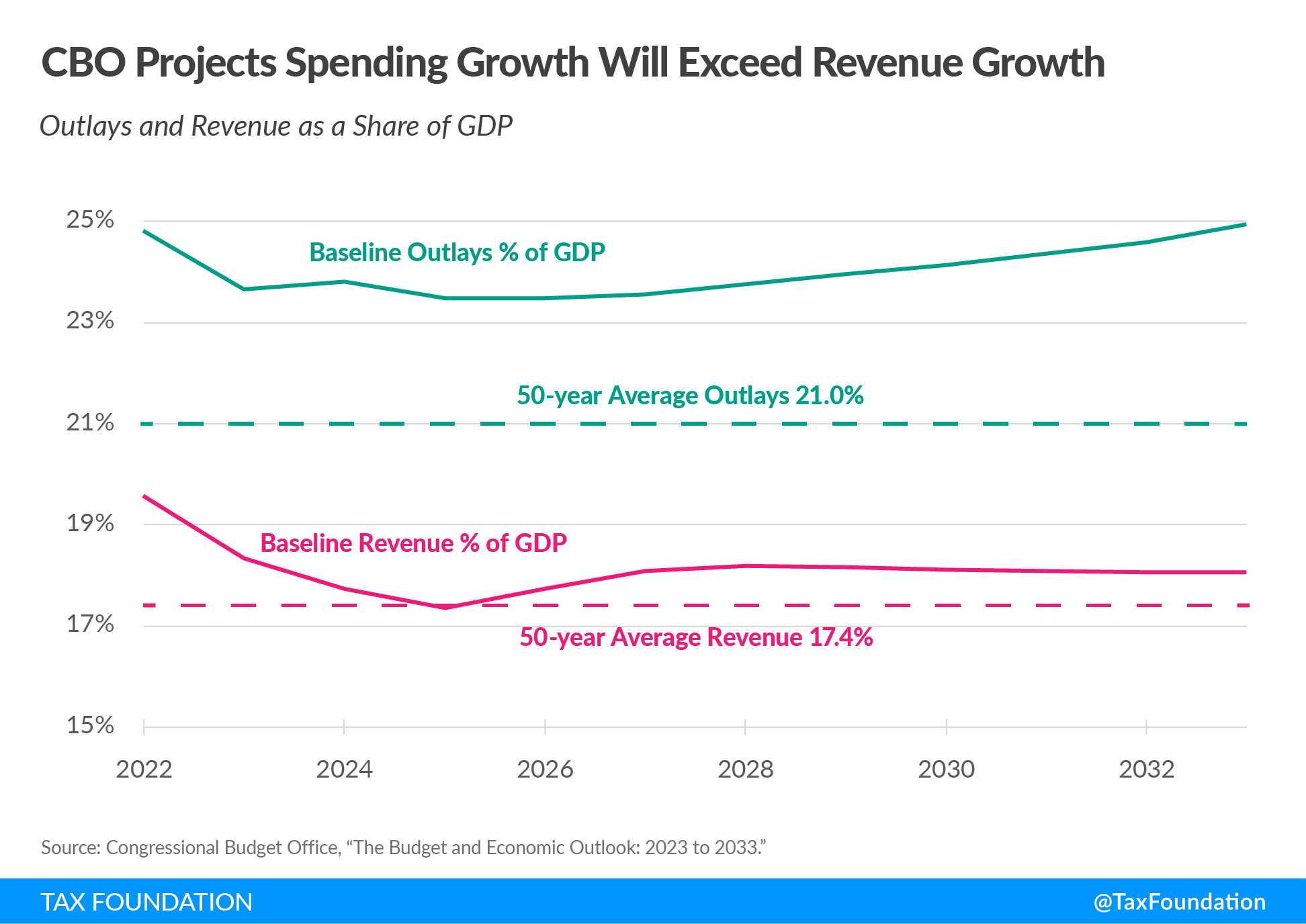

Separate from raising the debt limit to allow the Treasury to pay past obligations, the CBO projects that federal budget deficits will grow substantially over the next decade. Across the next decade (2024 through 2033), deficits will total more than $20 trillion, reaching an annual budget deficit of nearly $2.9 trillion in 2033 as spending growth outpaces revenue growth. The largest drivers of growing deficits are Social Security and Medicare. As a result, debt held by the public will grow each year, reaching 118 percent of GDP by 2033—larger than the size of the entire U.S. economy and the highest level ever recorded.

The longer Congress delays a fiscal solution to stabilize the debt, the more painful and large that solution will be. As the CBO explains, “Regardless of the policy option used to stabilize the debt, debt as a percentage of GDP—and thus the level at which debt would ultimately be stabilized—would rise the longer the process was delayed…” In other words, the tax hikes will be higher and the benefit cuts more severe.

Most recent measures to modify the debt limit have been accompanied by other budgetary measures. As Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute has noted, all eight major deficit-reduction laws since 1985 were attached to debt limit legislation.

As lawmakers consider options to address the underlying gap between spending and revenue going forward, they should draw on international experiences of fiscal consolidation.

In a recent survey of studies on the experience of countries around the world dealing with fiscal deficits and debt, the International Monetary Fund finds that successful fiscal consolidations (i.e., sustained improvements in deficits and debt-to-GDP levels) often involve both tax and spending measures. Reductions in social spending, as opposed to public investment, tend to produce more lasting fiscal improvements, as do less distortionary tax increases—including higher consumption, property, excise, and environmental taxes—and reductions in tax expenditures.

Other factors important for success include the public’s perception that the government will actually fulfill its commitments and that the adjustment will be gradual, not “front-loaded” with large structural policy changes. Overall, the successful consolidations often led to an annual improvement in the cyclically adjusted primary balance (deficit not counting interest) of 1 percent to 2 percent of GDP.

Although the authors did not reach a conclusion on whether tax or spending reforms (or both) are the best methods for reducing the debt, they still review some of the old literature that finds spending reductions are more effective in many cases that would be applicable to the U.S.: “[M]ore recent work still finds that expenditure-based consolidations could be expansionary under certain circumstances, such as in economies that are very open to trade or in those that start consolidation with high debt levels (exceeding 60 percent of GDP) and increased interest rate risk premiums.”

Further, other economists have concluded that fiscal consolidations based on spending cuts have had fewer negative effects on GDP than tax increases.

Looking at 16 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Alberto Alesina and his coauthors found that, on average, spending cuts were associated with mild recessions and in some cases no downturns at all, while almost all fiscal reforms based on tax increases were followed by “prolonged and deep recessions.” Fiscal adjustments based on tax increases reduced investment and business confidence. By contrast, business confidence rebounded almost immediately after a fiscal adjustment based on spending reforms.

Examining fiscal adjustments from a sample of 26 countries from 1995 to 2018, a Mercatus Center analysis found that successful consolidations, defined as one where the debt-to-GDP ratio declines by at least 5 percentage points in three years after the plan is implemented, were more spending-focused than tax-focused. More than half (53 percent) of expenditure-based fiscal consolidations were successful, compared to only 38 percent of tax-based ones. Balanced fiscal consolidations, however, had the highest success rate at 55 percent.

A European Central Bank analysis arrived at a similar conclusion: EU countries that pursued spending-based consolidations had higher growth rates five years following a fiscal consolidation announcement than those that pursued tax-based ones. While part of the difference in economic performance can be explained by better follow-through for revenue-based plans, the bulk of the difference was due to the composition of consolidations, with revenue having large, negative effects compared to nearly zero for spending.

The types of spending cuts and tax reforms that are part of a fiscal consolidation also matter.

In a follow-up paper, Alesina and his coauthors showed that cuts in transfers had milder negative effects on economic growth, nearing zero, compared to cuts in government consumption and investment, though both have relatively little impact on growth as compared to tax increases.

In a study of 17 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Norman Gemmell and other academics showed that reducing deficits by raising distortionary taxes, such as income taxes, consistently reduced economic growth, while raising less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, was more growth-enhancing. They found small positive growth effects from deficit-financed “productive” spending, such as infrastructure, implying that cutting such spending could hurt growth. However, negative growth effects from cutting productive spending would take longer to materialize, while negative effects of tax increases would be more immediate. Deficit-financed “nonproductive” spending, such as transfers, was shown to have a negative effect on long-run economic growth, suggesting that cutting them would boost growth.

In all, the experience with successful fiscal consolidations suggests they should be gradual and spending focused, with careful consideration of the growth effects of selected policies. If tax increases are included in a package, it is most efficient to focus on less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, or rationalizing tax expenditures and broadening the tax base.

Lawmakers must act swiftly to lift the debt limit and make good on our obligations. Whether attached to the debt limit, they should adopt the same sense of urgency in the effort to rein in our deficits and debt, paying mind to international experiences on successful fiscal consolidations.

Note: This blog post is the first in a series in which our experts explore the issues and potential solutions for America’s growing debt and deficits.