CVC Files Appeal Brief in Interference No. 106,115 | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (like its predecessor, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences or BPAI) occasionally renders an opinion having the tendency to raise an eyebrow or two, which on occasion has led the Federal Circuit, like its predecessor the Court of Claims and Patent Appeals, to offer a correction (the exercise of such tendencies no doubt leading to the vigor with which the Patent and Trademark Office pursued correction of the Federal Circuit by the Supreme Court, in Dickenson v. Zurko). The Board’s recent decision in Interference No. 106,115 between the Broad Institute, Harvard University, and MIT (collectively, “Broad”) as Senior Party against Junior Party the University of California/Berkeley, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (collectively, “CVC”) (see “PTAB Grants Priority for Eukaryotic CRISPR to Broad in Interference No. 106,115”) has raised more than a few eyebrows, and CVC’s brief on appeal to the Federal Circuit seeks to convince the Court that once again correction is in order.

To recap, the Board was convinced by Broad’s arguments that CVC’s attempts to reduce eukaryotic CRISPR to practice were unavailing until after Broad’s reduction to practice as evidenced by a manuscript submitted on October 5, 2012. Operating on the legal principle that “priority of invention goes to the first party to reduce an invention to practice unless the other party can show that it was the first to conceive of the invention and that it exercised reasonable diligence in later reducing that invention to practice,” Cooper v. Goldfarb, 154 F.3d 1321, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 1998), the Board was unconvinced that CVC’s March 1, 2012 conception satisfied the requirements of “complete” conception. Using much of the same argument (albeit for different purposes) as it had to prevail in Interference No. 106,048 (see “PTAB Decides CRISPR Interference in Favor of Broad Institute — Their Reasoning”), the Broad persuasively argued that the evidence of CVC’s attempts to reduce eukaryotic CRISPR to practice showed sufficient uncertainty and failures for the Board to conclude that CVC did not satisfy the requirements for conception. On this evidence the Board was unpersuaded that all that had been needed was the application of routine experimentation using the sgRNA detailed in CVC’s March 1st priority statement. Nor was the Board convinced that Broad derived the embodiments of eukaryotic CRISPR that they reduced to practice embodying sgRNA only after Dr. Marraffini obtained it from CVC and disclosed it to the Broad inventors (see “CVC Files Reply to Broad’s Opposition to CVC’s Priority Motion”).

CVC begins its brief by asserting that its inventors, Professors Doudna and Charpentier invented CRISPR:

This case concerns who is entitled to patents for using that system to edit genes in eukaryotic (e.g., plant or animal) cells: Doudna and Charpentier, who invented the technology, announced it to the world, and received the Nobel Prize for it; or a scientist at the Broad Institute who took their design and then (along with many others) promptly reduced it to practice using routine methods.

On the contrary, they assert, the PTAB “awarded priority to Broad because it purportedly reduced the invention to practice first—even though the PTAB never identified any inventive contribution Broad made,” and that this result was “backward” and arrived at through “multiple legal errors.” This last assertion is intentional and critically important, because if the Federal Circuit is convinced that such errors were legal and not factual in nature then the Board’s decision will be entitled to no deference and CVC may avoid another affirmance (the result of Federal Circuit review of the Board’s decision in Broad’s favor in Interference No. 106,048; see “Regents of the University of California v. Broad Institute, Inc.”).

The legal errors asserted by CVC include: 1) that the Board improperly did not use an objective standard to judge CVC’s conception, but rather required evidence that CVC inventors knew CRISPR would work in eukaryotic cells; 2) that the Board awarded priority to Broad without there being anything inventive done by Broad that they didn’t get from CVC; and 3) requiring that the written description of CVC’s applications in suit were sufficient to “persuade skeptical artisans the invention would overcome various imagined hurdles to reduction to practice in eukaryotic cells” rather than merely allowing them to identify the invention, which was contrary to the Court’s instruction that written description “”is not about whether the patentee has proven to the skilled reader that the invention works,” citing Alcon Rsch. Ltd. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 745 F.3d 1180, 1190 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

These assertions are distilled into three Issues Presented for the Court:

1. Whether the PTAB legally erred by failing to apply an objective standard for conception, and/or impermissibly awarded priority without identifying any inventive contribution by the purported inventor.

2. Whether the PTAB’s analysis is arbitrary and capricious.

3. Whether the PTAB applied an erroneous legal standard to conclude that CVC’s first and second provisional applications lacked written description.

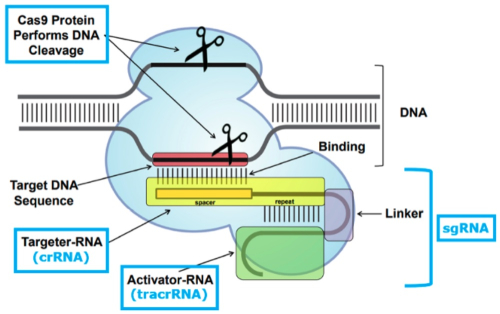

After a factual background, the brief reaches the legal arguments CVC relies upon to support its earlier assertions regarding the PTAB’s decision. These are generally aimed at supporting CVC’s assertions that how to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 complexes was known in the art from earlier work with zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). Adapting the CRISPR-Cas9 system to cleave DNA (any DNA) was, according to the brief, a consequence of the CVC inventors recognizing that a combination of Cas9, crRNA, and tracrRNA was enough to effect cleavage, and their further (“crucial”) recognition that the crRNA and tracrRNA could be combined into a single-guide, chimeric RNA (sgRNA), illustrated by this figure:

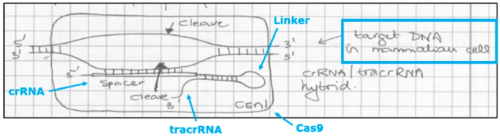

And this copy of the laboratory notebook page where sgRNA was first conceived by CVC:

In addition to citing contemporary statements from the CVC inventors regarding how their CRISPR-Cas9 system could be used, the brief also walks through the disclosures of CVC’s first provisional application (P1, USSN 61/652,086, filed May, 2012) and mentions summarily the other two provisionals (P2, filed October 19, 2012 and P3, filed January 28, 2013, the latter being the only provisional to which the Board ruled CVC was entitled to priority), illustrating the disclosure that supported their priority entitlement arguments and specific disclosure related to CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage in eukaryotic cells. (The brief also follows the consistent pattern of CVC mentioning the acclaim its inventors experienced upon their disclosure of CRISPR-Cas9 up to and including the Nobel Prize.)

These encomiums provided a basis for CVC to make its next argument, that the scientific community appreciated the significance of CVC’s CRISPR-Cas9 and rapidly applied it to eukaryotic cells because it was evident that it could be so applied. “The question ‘was not whether the CRISPR-Cas9 system would work in eukaryotes’—skilled artisans ‘all expected it would,'” they state, “but whether it would ‘outcompete the existing genome-editing technologies, such as TALENs and ZFNs.'”

As for CVC’s own efforts (the success, confidence in, and putative failures entailed were argued successfully by Broad as evidence of failure to achieve complete conception), the brief sets forth its planned activities (in some detail) to show actual reduction to practice during the summer and fall of 2012. These plans included using expression vectors to introduce nucleic acids encoding Cas9 and sgRNA under control of transcription promoters by which the CRISPR-Cas9 components would be expressed in the cell, and microinjection techniques where the pre-formed CRISPR-Cas9 complex would be directly introduced into the cell nucleus.

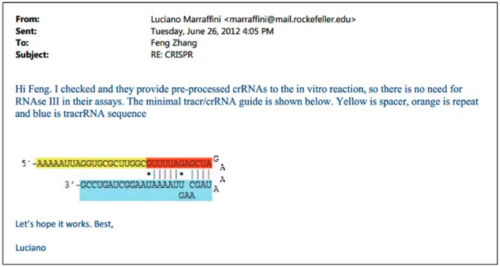

Having shown CVC’s own plans, the brief sets forth examples of many other laboratories showing CRISPR-Cas9 activity in eukaryotic cells. One of these was the Broad itself, which CVC’s explains with the preface “After Obtaining CVC’s Chimera A Before Publication, Broad Promptly Reports Reduction to Practice,” reciting the tale of Dr. Marraffini’s “improper” disclosure of this aspect of CVC’s invention to Broad inventors. In this telling, however, CVC emphasizes Broad’s putative record of failures, due to (according to CVC) that those inventors’ “did not understand that mature tracrRNA was a necessary third component of the final DNA-cleavage complex” and thus they had “no idea that mature tracrRNA and crRNA could be linked to form sgRNA.” “All that changed on June 26, 2012,” CVC asserts, which is the day Dr. Marraffini disclosed sgRNA to the Broad inventors by sending this e-mail containing the drawing (that at the time was under confidential review) showing the sgRNA structure (something CVC asserts Broad never disclosed until discovery in this interference):

(CVC also showed a comparison (substantial identity) between its sgRNA structure and the one disclosed in a scientific paper from the Broad group, Cong 2013, published in January 2013).

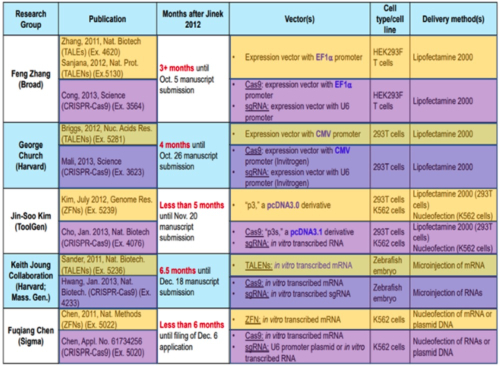

And as it had before the Board, CVC sets forth the results reported from four other groups during this period, with the following comparison of the methods, reagents, and techniques used:

At the same time CVC set forth its history of reduction to practice (although all but the most casual of readers would note that the first such reduction was achieved in October 2012, 4 months after CVC’s disclosure of sgRNA in June). One explanation for this delay recited obliquely in the brief was that “Doudna’s laboratory was ill-equipped for human-cell experiments” and thus had to rely on someone not having ordinary skill in the art (a graduate student “from a neighboring lab”) to perform the experiments that turned out to be crucial to Broad’s ability to convince the Board of CVC’s failures of achieving complete conception. (In addition, this narrative casts in perhaps their best light the history of difficulties experienced by CVC in obtaining actual reduction to practice; for example, in describing the experiments that ultimately did show CRISPR-Cas9 mediated cleavage the brief notes that they employed “the same basic vectors Jinek designed by June: an sgRNA vector with a U6 promoter, and a codon-optimized Cas9 vector with a CMV promoter and an NLS.”) For the microinjection-based experiments, the brief chalks up their less than stellar results not as failures but the consequence of having fewer resources than other labs and the decision not to publish having to do more with no opportunity to publish in a “high impact” journal than a perception of failure by CVC’s inventors and collaborators.

After setting forth its explication of the course of proceedings below (including the ‘048 Interference) CVC sets forth its legal arguments. First, CVC argues that the Board erred by departing from the legal standard of conception, which they argue is objective — was conception complete enough for the skilled worker to put the invention into practice (wherein the success of other labs, including at the Broad, should have been sufficient evidence of complete conception that any purported difficulties the CVC inventors and collaborator encountered would not be dispositive)? Second, CVC asserts that “[t]he PTAB erroneously rejected CVC’s originality challenge” (that sgRNA was CVC’s invention that Broad used in its practice of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells). This error arose because:

The PTAB identified nothing [Broad inventor] Zhang added that CVC had not already conceived, much less anything in the count. For good reason: Zhang obtained the blueprint for CVC’s invention—including CVC’s chimera A sequence and the use of the invention in eukaryotes—from CVC’s unpublished manuscript. Zhang cannot be the inventor when he added nothing but instead (improperly) obtained every limitation of the count from CVC.

Third, CVC asserts the Board’s decision was contrary to the standards under the Administrative Procedures Act imposed on administrative agencies, because “[i]t failed to connect its conclusions to its findings, and repeatedly ignored relevant evidence.” Finally, CVC argues that the Board applied the wrong legal standard for written description (a question of fact) by imposing the requirement that CVC demonstrate with experimental evidence that CRISPR would work in eukaryotic cells (which requirement was dependent on the Board being convinced by Broad’s arguments to the contrary and abetted by CVC’s purported failure to so demonstrate, at least not satisfactorily). In CVC’s view, “[t]he inventor’s obligation is to tell artisans what she invented, not convince skeptics the invention will work.”

In support of their first argument CVC cites Cameron & Everett v. Brick, 1871 C.D. 89, 90 (Comm’r Pat.), Amgen, Inc. v. Chugai Pharm. Co., 927 F.2d 1200, 1206 (Fed. Cir. 1991), and Sewall v. Walters, 21 F.3d 411, 415 (Fed. Cir. 1994), for the proposition that the Board committed two legal errors. First, conception must be “definite and permanent,” which CVC maintains it was because it satisfied the standard that its CRISPR invention could be (and was) disclosed in its priority documents (specifically P1), illustrating “possession of an operative method of making it.” The evidence CVC relies upon in this part of its argument is the success of others skilled in the art, and the Board’s error CVC asserts is in relying on its own difficulties and purported failures in reducing eukaryotic CRISPR to practice. “Whether the inventor succeeds promptly is irrelevant when the evidence shows the invention is sufficiently firm, definite, and developed that skilled mechanics can do so—and the evidence [here] shows they did,” the brief argues. And the subjective requirement imposed by the Board, that the CVC inventors knew the invention would work is contrary to Federal Circuit precedent, which contains no requirement of either expectation not knowledge that a completely conceived invention would work, CVC citing Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 1994); and Univ. of Pittsburgh of Commonwealth Sys. of Higher Educ. v. Hedrick, 573 F.3d 1290, 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Their argument hies back to Mergenthaler v. Scudder, 11 App. D.C. 264, 276 (1897), for the well-worn aphorism of patent law that “[c]onception is the ‘formation, in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention, as it is thereafter to be applied in practice,'” wherein “[t]he ‘true date’ of conception is ‘the point where the work of the inventor ceases and the work of the mechanic begins.'” Put succinctly in CVC’s brief, conception is complete under this precedent “‘when one of ordinary skill in the art could construct the apparatus without unduly extensive research or experimentation,'” citing Sewall and Burroughs (emphasis in brief). This is precisely the case here, according to CVC, based on the success of others, including Broad, once the sgRNA component of the CRISPR-Cas9 complex had been disclosed by CVC. And the fact that “much patience and mechanical skill, and perhaps a long series of experiments” might have been necessary to reduce the invention to practice doesn’t negate conception, CVC argued, citing Barba v. Brizzolara, 104 F.2d 198, 202 (C.C.P.A. 1939); and Acromed Corp. v. Sofamor Danek Group, Inc., 253 F.3d 1371, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2001). Included in this litany is Dolbear v. American Bell Telephone Co., 126 U.S. 1 (1888) (the Bell patent case, reminding the Court that Alexander Graham Bell “could not himself construct a telephone that transmitted spoken words” (emphasis in brief)), as well as the Wright brothers who applied for their airplane patent almost a year before Kitty Hawk and the patent on using AZT to treat AIDS.

The reason for this wrong result by the Board, CVC argues, is that they asked the wrong question, focusing on whether the CVC inventors were able to reduce the invention to practice without experimentation. Encouraged by Broad the Board was led to their conclusion by the “failure” of the CVC inventors, as individuals of greater than ordinary skill in the art, to indicate incomplete conception, ignoring the success by others of ordinary skill in the art. “It is hard to imagine more powerful, objective, real-world evidence that conception was ‘complete,'” they argue, “than the fact that so many actually did “construct the apparatus without unduly extensive research or experimentation,” citing Sewall. This willful ignorance of the evidence by the Board asserted by CVC included evidence of the response of the conference attendees where Doudna disclosed sgRNA, the response of Dr. Marraffini himself, and “significance of [Broad inventor] Zhang’s alleged conception on June 26, 2012, the very day he learned of CVC’s invention” (emphasis in brief), followed by a litany of all the ways Broad’s reduction to practice mimicked CVC’s conception.

As to CVC’s purported failings, the brief argues the Board was “doubly wrong” first for relying on the necessity for experimentation per se to prove incomplete conception rather than whether these experiments required more than routine skill, citing Rey-Bellet v. Engelhardt, 493 F.2d 1380, 1387 (C.C.P.A. 1974). And second, in relying on “how the inventors or their collaborators fared, or what they said along the way” rather than “whether the inventors’ idea was sufficiently firm and definite that reduction to practice could be performed by “one skilled in the art without the exercise of invention,” illustrated by several examples including Bell’s telephone, Sewall and Acromed. And CVC contends that the case law relied upon by the Board (Alpert v. Slatin, 305 F.2d 891 (C.C.P.A. 1962)) can be distinguished here because in that case the only evidence was of the inventor’s failure to reduce to practice, whereas here several other laboratories were able to do so contemporaneously (which CVC argues the Board improperly characterized as nunc pro tunc conception).

Finally, in this portion of their argument, CVC addresses the subjective test for reduction to practice they allege the Board employed as being improper under City of Elizabeth v. Nicholson Pavement, 97 U.S. 126 (1877), Applegate v. Scherer, 332 F.2d 571, 573 (C.C.P.A. 1964); Dana-Farber Cancer Inst., Inc. v. Ono Pharm. Co., 964 F.3d 1365, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2020), and in particular Burroughs, where the Court held the inventors did not need to know whether the invention worked to have complete conception. CVC distinguished Hitzeman, relied upon by the Board, on the basis that in that case the Court merely held that for claims to a compound to be conceived the inventor must expect to be able to “produce” the composition (something CVC contends its inventors had done here, at least in vitro).

Next, CVC’s brief turns to the issue of originality and the evidence and argument asserted before the Board that Broad had merely reduced to practice eukaryotic CRISPR using CVC’s sgRNA after it was (improperly) disclosed to Broad’s inventors by Dr. Marraffini (an argument that loses some equitable force because the disclosure was public). According to CVC, the Board granted Broad priority without identifying any aspect of the invention original to their inventors. CVC points out that the Board presumed Broad made an inventive contribution (“there must have been differences”) (emphasis in brief) because the Broad inventors succeeded in reducing the invention to practice while CVC’s inventors had not (what CVC terms the “ipse dixit” determination). This conclusion, CVC maintains, was arrived at by the Board without considering much less determining “whether Zhang added anything inventive or was just a more efficient (or luckier) mechanic ” (emphasis in brief). The reason for this situation is clear to CVC: the Board did not make findings of anything inventive by the Broad inventors because they could not — “[Broad inventor] Zhang got the invention from CVC.” For CVC, the Board’s decision “flouts the requirement that patents be awarded to an ‘original inventor’—not a ‘borrower or a copyist,'” citing 1 W. Robinson, The Law of Patents for Useful Inventions § 58 (1890) (as well as the U.S. Constitution) and Applegate. Ironically, CVC argues that, had CVC hired Broad’s inventor to reduce the invention to practice under these circumstances it would be beyond dispute that CVC’s inventors would have prevailed.

The brief then sets forth CVC’s argument that the Board violated the provisions of the APA for reasoned decision making and should be considered “arbitrary and capricious,” “otherwise not in accordance with law,” or “unsupported by substantial evidence,” giving the Federal Circuit several ways to at least vacate the Board’s decision for remand. These arguments rely for their facts on what CVC set forth above: for example, that the Board found in favor of the Broad inventors without any evidence of inventive contribution to CVC’s conception (the ipse dixit, “there must have been differences” standard). CVC contends that the APA requires that “[a]gency decisions must be grounded in evidence,” citing Morall v. DEA, 412 F.3d 165, 178 (D.C. Cir. 2005), and evidence CVC contends was lacking for this conclusion (and in at least one instance involving use of the U6 promoter to make sgRNA CVC contends the Board committed a mistake of fact). CVC cites the principle that “[c]ourts cannot ‘uphold agency action if’ the agency decision ‘fails to consider “significant and viable and obvious alternatives,'” citing Dist. Hosp. Partners, L.P. v. Burwell, 786 F.3d 46, 59 (D.C. Cir. 2015), which “precisely describes the situation here” according to CVC. Moreover, CVC asserts that the frequency of Broad’s successes (0.75%) was sufficiently low that “many experiments may fail to demonstrate cleavage due to random chance” or “human error,” “equipment quality,” or “measurement failures” (or the fact that CVC’s experiments were performed initially by a graduate student and CVC achieved success when a more experienced experimentalist took up the task, without and change in the protocol). And some of those “failures” were attempts at CRISPR reactions that were outside the scope of the Count and thus should not have been applied to the Board’s calculus. The Board ignored “rafts” of evidence contrary to its conclusions, CVC states, including contemporaneous encomiums by scientists like Dr. Marraffini about sgRNA-based CRISPR; the timing of other laboratories successes relative to CVC’s inventors’ disclosure of sgRNA-based CRISPR; the persistence (“stability”) of CVC’s protocol, which did not change throughout its attempts to produce actual reduction to practice; and with regard to the subjective standard, that CVC’s inventors never believed the protocols would not be successful despite the highly touted expressions of doubt asserted by Broad to support its incomplete conception narrative. And CVC brings forth an argument it made during Final Hearing to the effect that the four months it took for CVC to reduce the invention to practice was not a significant delay (the Wright brothers took almost a year to achieve powered human flight, for example). In some ways playing their trump card, CVC states that “[n]owhere did the PTAB explain why the inventors awarded the Nobel Prize for probably the most stunning advance of the century should be disqualified because their graduate students initially stumbled but ultimately succeeded in just four months.” CVC makes similar arguments regarding CVC’s microinjection experiments and accuses the Board of conflating the requirements of these experiments with vector-based expression of CRISPR-Cas9 in eukaryotic cells.

Finally, the brief addresses the Board’s decision to deny priority benefit to CVC’s earlier P1 provisional application based on lack of written description, saying the Board applied the wrong standard once again. In interferences, CVC states, all that is required is that a priority document describe one embodiment falling within the scope of the Count, citing Falkner v. Inglis, 448 F.3d 1357, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2006). Because the P1 provisional described a protocol for eukaryotic CRISPR that others (including Broad) followed to achieve the result and that protocol was what CVC’s inventors ultimately themselves reduced to practice CVC’s P1 application satisfied the standard. The brief sets forth in detail (as CVC has done throughout the interference before the Board) what is disclosed in P1 and how the methods for practicing CRISPR in eukaryotic cells were conventional techniques used in earlier cleavage regimes like ZFN and TALENs. The Board in error, CVC maintains, applied a “burden to convince,” contrary to the Court’s instructions in Alcon that:

Written description “is about whether the skilled reader of the patent disclosure can recognize that what was claimed corresponds to what was described.” . . . Consequently, this Court has warned, it “is not about whether the patentee has proven to the skilled reader that the invention works, or how to make it work.”

Written description does not require that the person of ordinary skill be persuaded that an invention works, nor does delay during the application of diligence negate the existence of an adequate written description, CVC asserts, citing BASF Plant Sci., LP v. Commonwealth Sci. & Indus. Rsch. Org., 28 F.4th 1247, 1267 (Fed. Cir. 2022) — again stating that the Board applied the wrong standard regarding what is required to provide an adequate written description under the statute. What is required, CVC argues, is a description, not evidence that the described invention works, and here the successes of other labs, including Broad’s, and the CVC inventors’ eventual success establishes that CVC’s P1 priority document contained the required description. While possession is required proof is not, according to the brief, and the Board’s imposition of the proof requirement was another error CVC lays at the Board’s doorstep. CVC cites the Board’s differential treatment of P1 (not adequately described) and P3 (satisfies written description requirement) to illustrate the point, because the only difference between these two priority documents is that the P3 application included a working example of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells. CVC closes this portion of the brief by reminding the Court that an inventor could never foreclose the possibility that an invention might not work, because:

No inventor can anticipate and preempt with instructions every single litigation-inspired hypothetical problem that can be conjured. Lawyers can always imagine 1,001 reasons an invention might not work. Paid experts can invent still more.

“Possession” in this context, CVC asserts, means possession of the idea, the conception of the invention, nor “construction of a working example.” This is because, as CVC concludes its brief, the controlling principle is that “[t]he patent system does not punish inventors of breathtaking innovations by saddling them with the burden of convincing putative skeptics their invention will work.”