Court upholds California animal-welfare law

OPINION ANALYSIS

on May 11, 2023

at 2:35 pm

Under Proposition 12, pork products sold in California must come from breeding pigs that have, among other things, at least 24 square feet of living space. (The HSUS)

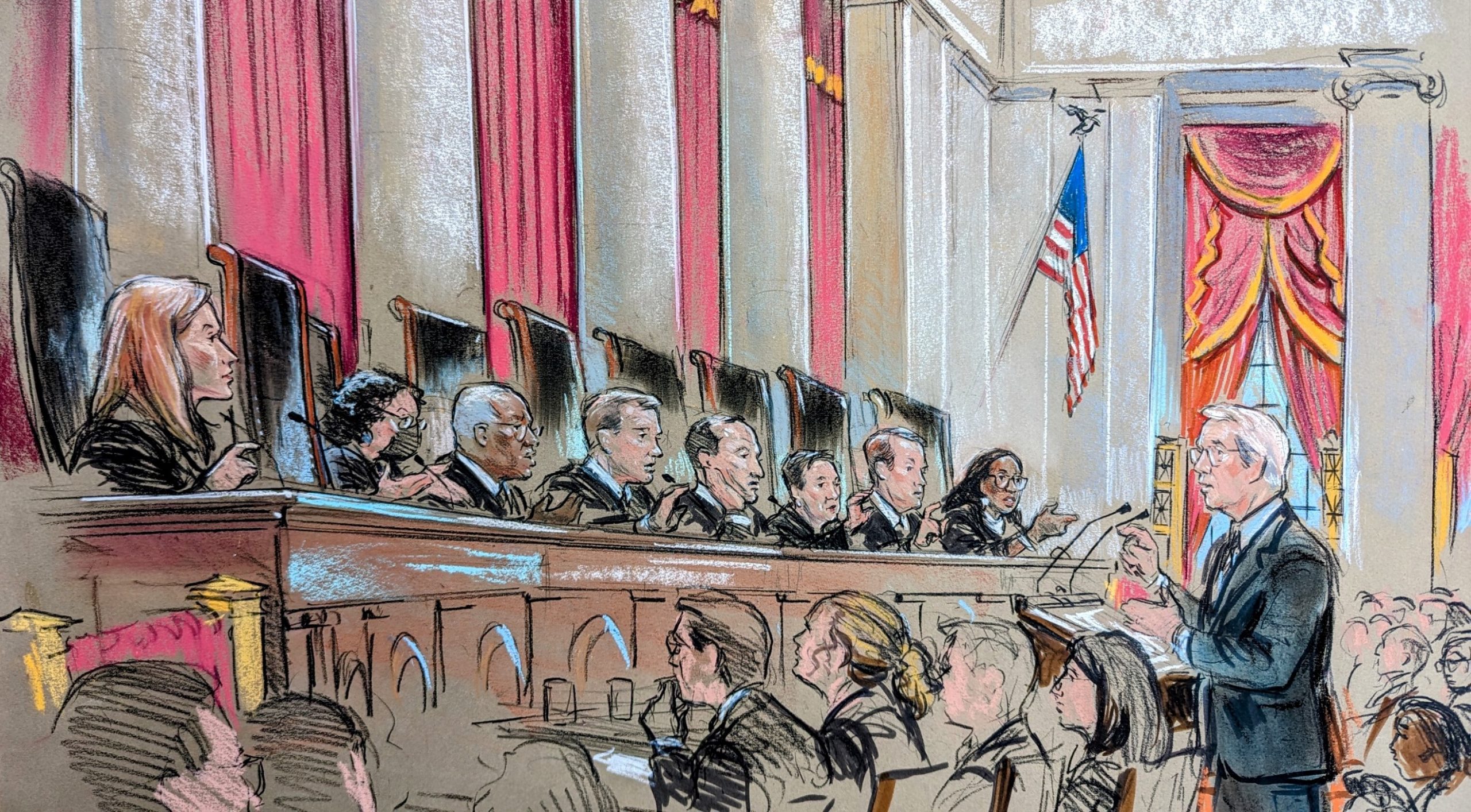

The Supreme Court on Thursday issued a major ruling that upheld a controversial California animal-welfare law. In a deeply splintered vote that did not break down on traditional ideological lines, the justices rejected an argument by pork producers that the law, known as Proposition 12, violates the Constitution by regulating the pork industry outside California.

Approved by California voters in 2018, Proposition 12 bars the sale in California of pork products when the seller knows or should know that the meat came from the offspring of a breeding pig (also known as a sow) that was confined “in a cruel manner.” This means, among other things, that sows must have at least 24 square feet of living space – about the size of two bath towels.

The National Pork Producers Council and the American Farm Bureau Federation went to federal court to challenge Proposition 12. They argued that the law violates a doctrine known as the dormant commerce clause – the idea that the Constitution’s delegation of power over interstate commerce to Congress precludes states from passing laws that discriminate against that commerce. In particular, they contended, states like California cannot require out-of-state businesses to operate in a particular way to sell their products in California. After the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit upheld the law, the challengers came to the Supreme Court, which heard argument in October.

Writing for the court, Justice Neil Gorsuch began by rejecting the challengers’ first argument – the idea that the Supreme Court’s cases interpreting the dormant commerce clause have created a rule that prohibits virtually all state laws that have the “practical effect of controlling commerce outside the State,” even if the laws do not intentionally discriminate against out-of-state economic interests. But the cases on which the challengers rely, Gorsuch explained, do not establish any such rule. “Instead,” he observed, “each typifies the familiar concern with preventing purposeful discrimination against out-of-state economic interests.” And the rule that the challengers posit, Gorsuch continued, “would cast a shadow over” a broad range of existing state laws that are widely regarded as constitutional, even though they may affect behavior outside the states that enact them – for example, state income-tax laws, which often prompt both individuals and companies to relocate to other states.

The challengers had also made a second argument: Under the Supreme Court’s 1970 decision in Pike v. Bruce Church, they contended, Proposition 12 should fall because its benefits for California residents do not outweigh the costs it imposes on out-of-state economic interests. But that argument fell short as well.

Three justices – Gorsuch, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett – would have ruled that courts do not have the power or the ability to undertake the kind of balancing test that the challengers propose. “How,” Gorsuch asked, “is a court supposed to compare or weigh economic costs (to some) against noneconomic benefits (to others)?” “Really,” Gorsuch continued, “the task is like being asked to decide ‘whether a particular line is longer than a particular rock is heavy.’” If the challengers are correct that Proposition 12 “really does threaten a ‘massive’ disruption of the pork industry,” Gorsuch concluded, they can lobby Congress to intervene instead.

But six other justices disagreed with Gorsuch, Thomas, and Barrett on this point. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote an opinion concurring in part that was joined by Justice Elena Kagan, while Chief Justice John Roberts wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part that was joined by Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Those justices agreed that courts can still consider Pike claims and balance a law’s economic burdens against its noneconomic benefits, even if (as in this case) the challengers do not contend that the law has a discriminatory purpose.

Those six justices did not agree, though, on what should happen to the challengers’ claim in this case. A different group of four justices – Gorsuch, Thomas, Sotomayor, and Kagan – agreed that the claim cannot go forward. Even if courts can consider the challengers’ claim, Gorsuch explained, the challengers cannot meet Pike’s initial requirement of showing that Proposition 12 imposes “substantial burdens” on interstate commerce. In this case, Gorsuch wrote, although the challengers’ complaint contends that “some out-of-state firms may face difficulty complying (or may choose not to comply) with Proposition 12,” out-of-state producers have other options, such as giving their pigs “the space the law requires” or designating some of their operations for sale in California, while not complying with Proposition 12 in other parts of their operations.

The Roberts opinion would have found that the challengers had alleged a substantial burden from Proposition 12 – for example, increased costs to comply with the law that could reach as much as $348 million, as well as “consequential threats to animal welfare and industry practice.” He therefore would have invalidated the 9th Circuit’s decision in favor of the state and sent the case back for the court of appeals to determine whether the challengers have alleged that those substantial burdens outweigh California’s interests in enforcement of the law. But his approach did not garner a majority, and so the lower court’s decision stood.

Kavanaugh penned a separate solo opinion that voiced a concern that surfaced among several justices at the oral argument in October. With Proposition 12, Kavanaugh posited, California “has attempted, in essence, to unilaterally impose its moral and policy preferences for pig farming and pork production on the rest of the Nation.” Not only does the law “undermine[] federalism and the authority of individual States by forcing individuals and businesses in one State to conduct their farming, manufacturing, and production practices in a manner required by the laws of a different State,” Kavanaugh warned, but it also “could provide a blueprint for other States” to pass other laws to advance their policy preferences in the future, on issues ranging from illegal immigration to abortion.