Court seems unwilling to embrace broad version of “independent state legislature” theory

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Dec 7, 2022

at 5:22 pm

A few protesters hold signs as members of the public line up to attend Wednesday’s argument in Moore v. Harper on a rainy morning in Washington, D.C. (William Hennessy)

The Supreme Court on Wednesday signaled that it may not be ready to adopt a sweeping interpretation of the Constitution, known as the “independent state legislature” theory, that would give state legislatures broad power to regulate federal elections without interference from state courts. Although some justices appeared receptive to that theory during nearly three hours of argument, it was not clear that there was a majority to endorse it, even as other justices focused on a narrower version of the theory that would preserve at least some role for state courts in enforcing state laws or the state constitution.

The dispute before the court in Moore v. Harper arose from a challenge to a new congressional map adopted by North Carolina’s Republican-controlled legislature in early November 2021. The North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the map after finding that it was a partisan gerrymander in violation of the North Carolina constitution. The question for the justices is whether the state court overstepped its authority under the U.S. Constitution’s elections clause, which says the time, place, and manner of congressional elections “shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.”

Representing the Republican legislators, lawyer David Thompson maintained that the elections clause vests a state’s legislature with the power to make rules for federal elections. State courts cannot, he stressed, restrict a legislature’s substantive discretion to do so. Instead, he argued, state courts can only enforce procedural limits on the legislature’s authority.

David Thompson argues for North Carolina Republican legislators. (William Hennessy)

Members of the court saw two main problems with Thompson’s argument. The first was the Supreme Court’s own precedent. Justice Elena Kagan ticked off a series of Supreme Court cases that, she said, make clear that state courts, applying a state’s constitution, can constrain the legislature’s power over federal elections.

Kagan later observed that Thompson’s argument was “a theory with big consequences” that could eliminate most of the “normal checks and balances” in government “at exactly the time when they are needed most” – such as the redistricting in this case, in which legislators have a strong incentive to create a map that will keep them in power. That’s why, Kagan noted, the Supreme Court has made clear that the legislature is subject to normal constraints even under the elections clause.

Chief Justice John Roberts also voiced skepticism about the broad power that Thompson was asserting. Thompson agreed with Roberts that a governor’s veto can limit the legislature’s power under the elections clause, pointing to the Supreme Court’s 1932 decision in Smiley v. Holm, in which the justices upheld the Minnesota governor’s veto of a congressional map enacted by the state legislature. Smiley, Roberts said, is “a pretty significant exception” that “undermines the legislature’s argument that it can do whatever it wants.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch had a different view. State legislatures have not uniformly regarded themselves as limited by their state constitutions on election issues, he said. During the Civil War, he observed, state constitutions would have barred absentee votes for soldiers stationed away from home, but the state legislatures refused to adhere to those limits. And he suggested that limits imposed by a governor’s veto, as in Smiley, are different from limits imposed by state courts, because the veto can be regarded as sharing legislative power.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson saw a related problem. In her view, because the state constitution creates the state legislature, the constraints contained in the constitution must apply to the legislature, even when it comes to the legislature’s power under the elections clause.

The justices raised a second set of concerns about Thompson’s proposed distinction between substantive limits on the legislature’s discretion and procedural ones. How, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Thompson, do you draw a line between those two sets of limits? Trying to do so, she suggested, would be a “logical morass.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett appeared to agree, calling the distinction between substantive and procedural limits “notoriously difficult lines to draw.”

Thompson later offered an alternative option to the substantive/procedural distinction. Another possibility, he noted, would allow state courts to intervene to enforce the state constitution when there are “judicially discoverable and manageable” standards for the courts to use – for example, very specific rules about how to determine whether a map is the product of partisan gerrymandering. In this case, Thompson contended, the North Carolina Supreme Court relied on a provision in the state constitution that guarantees the right to free elections. That concept, he told Justice Sonia Sotomayor, is amorphous, so the court usurped the legislature’s policymaking function in interpreting it here.

Arguing on behalf of Democratic voters and non-profits that challenged the legislature’s congressional map, lawyer Neal Katyal cautioned that adopting Thompson’s theory would lead to the invalidation of “hundreds” of state constitutional provisions.

Neal Katyal argues for private respondents in Moore v. Harper. (William Hennessy)

This argument seemed to gain some traction with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who stopped short of endorsing a sweeping interpretation of the elections clause that would give legislatures near-complete authority. Nearly all state constitutions regulate federal elections, he observed. How, he asked Thompson, should the court deal with this historical practice in deciding this case?

Instead, Kavanaugh appeared receptive to a version of the theory, outlined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist in a concurrence in Bush v. Gore, that would still preserve a role for state courts – subject to oversight by federal courts if they went seriously astray.

Perhaps seeing this theory as the lesser of two evils, Katyal did not push back, although he insisted that the standard for a federal court to invalidate the state court’s interpretation would be “sky high.” And Don Verrilli, arguing on behalf of North Carolina executive-branch officials, suggested a possible test, which he characterized as the “best distillation” of Rehnquist’s concurrence in Bush v. Gore: whether the state court decision is “such a sharp departure from the state’s ordinary modes of constitutional interpretation that it lacks any fair and substantial basis in state law.”

Don Verrilli argues for the state respondents. (William Hennessy)

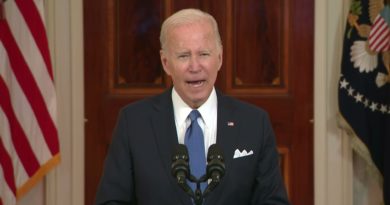

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar represented the Biden administration, which filed a brief supporting the Democratic voters and their allies. She too acceded to Kavanaugh’s version of the theory, emphasizing – like Katyal – that federal courts should be “very deferential” to state-court interpretations of state law. A state court would violate the elections clause, she added, if it is not acting as a court, but instead seizing the power to make policies.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argues for the United States. (William Hennessy)

Justice Samuel Alito appeared squarely aligned with Thompson and the legislators, and he resisted any suggestion that a ruling for them would pose a danger to American democracy. Noting that many state supreme courts are elected, he asked Katyal whether it advances democracy to transfer “the political controversy about redistricting from the legislature to elected supreme courts where the candidates are permitted by state law to campaign on the issue of redistricting.”

And Justice Clarence Thomas implied that opposition to the independent state legislature theory rested on partisanship, rather than constitutional principles. If the state legislature drew a map that was very generous to minority votes, he asked Katyal, but the state supreme court ruled that the map violated the state constitution, would you make the same argument? Katyal said yes.

Katyal warned that a ruling for the legislators would have a “blast radius” that would “sow election chaos” and lead to a flood of litigation. Faced with a scenario in which a state court had invalidated election regulations for state elections but not for federal elections, he added, states might have to hold two separate elections using two sets of rules.

Thompson concluded the oral argument with his own dire set of predictions. The state and the challengers, he told the justices, have also contended that a violation of the elections clause occurs when the state legislature is deprived of a “central role” in regulating elections. That test, Thompson said, would create “far more litigation.”

A decision in the case is expected by next summer.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.