Could In re Cellect be the End of Patent Term Adjustments? The Federal Circuit Will-Soon-Tell-Us

“This year, the Federal Circuit will decide whether a judge-made-doctrine can truncate a legislative grant of patent term adjustment…. In doing so it could craft a bright-line rule that a judge-made doctrine cannot cut off a statutorily authorized time extension.”

Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) was designed to serve an important purpose – to compensate patentees for time lost during examination due to U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) delays. Most industries rely heavily on their patent portfolios to drive business strategies that ultimately impact their bottom line. The impact of patent term is especially acute in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, where companies spend billions of dollars to develop new drugs. For these companies, every day that their patent is in force matters, generating millions in additional revenue. With so much at stake, companies strive to accrue all the patent term they are entitled to under the current statutory regime, including by way of PTA.

Confusion Sets In

The codification of PTA and Patent Term Extension (PTE)—the right to compensation for delays caused by regulatory approval processes—toward the end of the 20th century created a strange conundrum in light of the century-old common law doctrine of Obviousness-Type Double Patenting (OTDP). In all honesty, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit is to blame for the confusion. To begin with, in 2007, the court upheld the validity of a patent in Merck v. Hi Tech Pharmacal Co. that contained a PTE of 1,233 days. In reaching a conclusion on a key issue—unrelated to OTDP— the court offhandedly compared the statutory language of PTE and PTA. This threw off the lower tribunals in wondering whether the comparison was more than met the eye. To add fuel to the fire, seven years after its Merck holding, the Federal Circuit, in AbbVie v. Mathilda, invalidated a patent by disregarding 750 days of its PTA without even addressing whether PTA could properly be invalidated under OTDP. This drove the lower tribunals insane. An example would be the 2015 Michigan court’s ruling in which it invalidated a patent that expired after the reference patent solely due to PTA. Magna Elecs., Inc. v. TRW Automotive Holdings Corp., (W.D. Mich. Dec. 10, 2015). The court blatantly discounted the PTA, reasoning that in absence of a terminal disclaimer, the “earliest expiration date of all the patents” should control.

To date, courts have remained confused about the issue. Unlike in other areas of law, where tribunals respect the separation of powers doctrine, some courts, as well as the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB)—after the AbbVie decision—started encroaching more and more on the legislative power by reading between the lines of the statutory language. The circuit split raised several issues for the Federal Circuit, not the least of which was whether a judge-made-doctrine could truncate a statutory grant of term extension, be it PTE or PTA. Determined to rectify the developing issue, the Federal Circuit took another stab in the “Novartis cases.” However, the issue in the Novartis cases was limited to PTEs. In 2018, the Federal Circuit issued two opinions addressing whether OTDP invalidated PTE. In Novartis v. Breckenridge, the court upheld the validity of a patent having a five-year PTE. On the lower court’s position that “there [was] no case law supporting Novartis’s proposition that a term extension [immunized] a patent from [OTDP] challenge,” the court reversed. The court made explicit in Novartis v. Ezra what it implied in Breckenridge by affirming the lower court’s ruling that in cases where the challenged patent expired after the reference solely due to PTE, OTDP did not invalidate said challenged patent’s PTE. In doing so, the Ezra Court stressed that the underlying equitable concern of “potential gamesmanship [by the patentee] . . . through structuring of priority claims” did not exist here, therefore, the challenged patent was valid.

After the Federal Circuit resolved the issue surrounding OTDP and PTE, a New Jersey court extended its reasoning to OTDP and PTA. In Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp. v. Sandoz, Inc., Judge Wolfson first addressed whether a patent could serve as an OTDP reference if the sole reason the challenged patent expired after the reference was due to PTA. The court held no, reasoning that “[a] judge-made doctrine cannot cut off a statutorily authorized time extension.” In 2021, Judge Shipp, from the same district, addressed a similar issue in Amgen, Inc. v. Sandoz Inc. of whether the operation of both PTA and PTE invalidated a later-expiring patent under OTDP. The court held that “[a] difference in expiration dates between two patents that [arose] solely from a statutorily authorized time extension . . . [could not] . . . be the basis for an application of [OTDP].” Thus, after 2018, it seemed like the lower courts started to view both PTA and PTE through the same lens.

Enter, Cellect

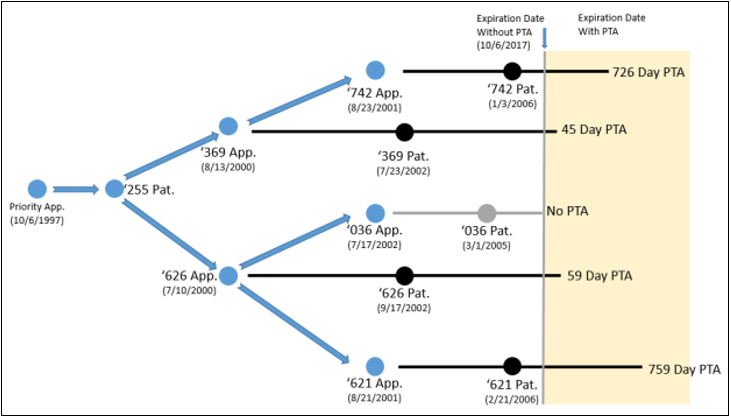

In December 2021, however, the PTAB took the opposite view in resolving whether PTA and PTE should be treated alike under OTDP. In Ex Parte Cellect, the inventors developed and patented the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor imaging technology. All Challenged Patents claimed priority to the same application and received varying PTA periods during prosecution.

The Challenged Cellect Patents and their respective PTA periods.

The Challenged Patent family was involved in several proceedings. The patentee appealed four ex parte reexamination decisions under OTDP. The issue before the Board was whether the Examiner erred in applying OTDP rejections to the expired Challenged Patents that had different expiration dates solely due to different PTA periods. The Board affirmed the Examiner’s decision. It distinguished PTA from PTE, opining that the statutory language of §154(b), unlike §156, was limited where terminal disclaimers were filed. According to the Board, as terminal disclaimers were applied after PTA, so too must OTDP – after all, they were “two sides of the same coin.” In the alternative, the Board reasoned, even if OTDP were applied before PTA, rejection would still be appropriate as two patents that were obvious variants and expired on the same day needed a terminal disclaimer to enforce common ownership. As the patentee had not filed one during prosecution, the Challenged Patents remained invalid. To justify its reasoning as equitable, the Board remarked that “any extra term of the second patent was itself what was inequitable.”

Cellect, LLC appealed to the Federal Circuit, raising the issues of: (a) whether PTA and PTE should be treated alike for purposes of OTDP; (b) whether a patent could become a basis for OTDP against a related patent when the two patents expired at different times solely due to PTA; and (c) whether the Board erred in finding that OTDP raised a substantial new question of patentability. Cellect argued that the Board erred in treating PTA and PTE differently, running afoul of Congressional intent and Federal Circuit precedent, citing Ezra. As time extensions from PTA and PTE were both properly granted by statute, the Board’s suggestion that adjustments, not extensions, could transform a related patent into an OTDP reference was erroneous. Cellect reminded the court that none of the equitable concerns underpinning the OTDP doctrine existed in the underlying case; instead, the Board unwarrantedly acted on a hypothetical concern of potential harassment by multiple assignees. Finally, Cellect argued that “the same question of patentability [had] already been . . . decided in an earlier concluded examination.”

In response, the USPTO maintained that the contrast in statutory language between §§ 154 and 156 made clear that terminal disclaimers cut off PTA, not PTE, thus the Board acted properly. The Office advised that applicants in similar situations could henceforth file preemptive terminal disclaimers to avoid OTDP determinations. Finally, according to the USPTO, there was insufficient evidence that OTDP was considered during prosecution. In its reply brief, Cellect further argued that “there was no support in the statute for the Board’s position that patents with no existing disclaimer . . . should be invalidated solely because the PTA extended the expiration date.” According to Cellect, the Patent Office erred in arguing that “Congress [in addressing terminal disclaimers] intended to address double patenting by proxy.” The parties, including several amici curiae, finished filing briefs in December 2022.

A Big Decision

This year, the Federal Circuit will decide whether a judge-made-doctrine can truncate a legislative grant of PTA. It is likely the Federal Circuit will reverse the Board’s decision. In doing so it could craft a bright-line rule that a judge-made doctrine cannot cut off a statutorily authorized time extension, be it PTE or PTA. Such a clear ruling warrants extending the Novartis cases to PTA, reading the statutory language of both PTA and PTE consistently, and rehashing the “absence of gamesmanship” justification in OTDP analyses. However, if the court affirms the Board’s decision, it would essentially be holding that absent terminal disclaimers, OTDP can be the basis for invalidating claims irrespective of PTA. Such a ruling would leave future applicants with the only absurd choice of filing preemptive disclaimers. However the Federal Circuit resolves the issue, it is clear that the court’s decision in In re Cellect, LLC will have a significant impact on the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, where every day of patent term matters.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 130330254

Author: Premium_shots