Cell Phone Tax Rates by State

Key Findings

- A typical American household with four phones on a “family share” plan paying $100 per month for taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

able wireless services would pay nearly $294 per year in taxes, fees, and government surcharges—down slightly from $305 in 2022. - Nationally, taxes, fees, and government surcharges make up a record-high 24.5 percent tax on taxable voice services. Illinois residents continue to have the highest wireless taxes in the country at 33.8 percent, followed by residents in Arkansas at 32.2 percent and Washington at 32.1 percent. Idaho residents pay the lowest wireless taxes at 13.7 percent.

- Texas had the largest increase of any state in 2023—from 24.1 to 28.3 percent—due to a large increase in the rate of the state Universal Service Fund charge.

- For the first time since 2017, the Federal Universal Service Fund charge rate decreased, dropping significantly from 12.2 percent to 10.8 percent. This reduction was offset by a sizeable increase in state and local wireless tax rates, from 13.2 percent to 13.7 percent.

- The federal Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act prevents state and local governments from imposing taxes and fees on wireless internet access. Without this federal prohibition, taxes and fees that apply to wireless voice services could be applied to internet access and significantly increase the tax burden on wireless bills.

- Since 2012, the average charge from wireless providers decreased by 26 percent, from $47.00 per line per month to $34.56 per line. However, during this same time, wireless taxes, fees, and government surcharges increased from 17.2 percent to 24.5 percent of the average bill.

- Roughly 78 percent of low-income adults and 72 percent of all adults lived in wireless-only households. Wireless taxes are regressive and create significant burdens on low-income families.

Introduction

Taxes and fees on the typical American wireless consumer decreased slightly this year, from 25.4 percent of a typical monthly bill in 2022 to 24.5 percent in 2023. This total includes state and local taxes averaging 13.7 percent and the Federal Universal Service Fund (FUSF) rate of 10.8 percent.[1] State and local taxes and fees increased from 2022 to 2023, but this increase was offset by a FUSF rate reduction from 12.2 percent to 10.8 percent.

This is the 14th edition of our report tracking the taxes, fees, and government surcharges imposed on wireless voice service by federal, state, and local governments. Our methodology remains consistent. We compare the percentage rates of the taxes, fees, and government surcharges imposed on taxable wireless services, referred to hereafter collectively as “tax.” Flat rate impositions, such as a $1.00 per month per line 911 fee, are converted to a percentage using the average monthly industry revenue per line as tracked by the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association (CTIA).

Over time, markets, product offerings, and government policies change. To incorporate these changes in our report, we also include an alternate calculation. Federal law prohibits states from taxing internet access—including data plans—and internet access makes up over half of the cost of an average wireless consumer’s bill. To show how this limitation impacts tax collections and effective tax rates, we also calculate taxes paid as a percentage of combined taxable and non-taxable services. As data makes up a greater portion of our wireless consumption every year, services and products offered by wireless companies have adapted.

The wireless market has become increasingly competitive. The result has been steady declines in the average price for wireless services. Over the last decade, the average monthly revenue per wireless line has fallen from $47.00 per month to $34.56 per month. Unfortunately, this price reduction for consumers has been partially offset by higher taxes.

There were about 523 million wireless subscriber connections at the end of 2022.[2] Wireless subscribers will pay approximately $12.6 billion in taxes, fees, and government surcharges to state and local governments in 2023 based on the tax rates calculated in this report:

- $5.3 billion in sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding.

es and other non-discriminatory consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or an income tax where all savings is tax-deductible.

es that apply to other taxable goods and services - $3.8 billion in state and local 911 and 988 fees, which includes hundreds of millions of dollars that are not actually used for 911 purposes in some states

- $3.5 billion in additional telecommunications-specific taxes

Wireless services are often the sole means of communication and connectivity for Americans, especially younger people and those with low incomes. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 78 percent of all low-income adults lived in wireless-only households and 72 percent of all adults lived in wireless-only households in 2022.[3] The $7.3 billion in state and local taxes and fees that are levied in addition to sales taxes disproportionately impact Americans least able to afford them.

Wireless Taxes and Fees Drop for the First Time Since 2017

Taxes, fees, and government surcharges on wireless services fell for the first time since 2017, driven by a reduction in the Federal Universal Service Fund rate. The state and local burden increased significantly, from 13.15 percent to 13.70 percent, while the FUSF surcharge rate decreased from 12.2 percent to 10.8 percent. Table 1 highlights the changes in wireless tax rates from 2003 to 2022.

The FUSF surcharge increased steadily since 2017, making the rate reduction in 2023 welcome news for wireless consumers. Previous rate increases had been driven by the decline in the price of telecommunications services, combined with the shift in consumer purchases from telecommunications services to internet access. This forced the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to increase rates just to keep revenues constant. It remains to be seen whether the 2023 reduction is an anomaly or a shift away from the trend toward increasing FUSF rates.

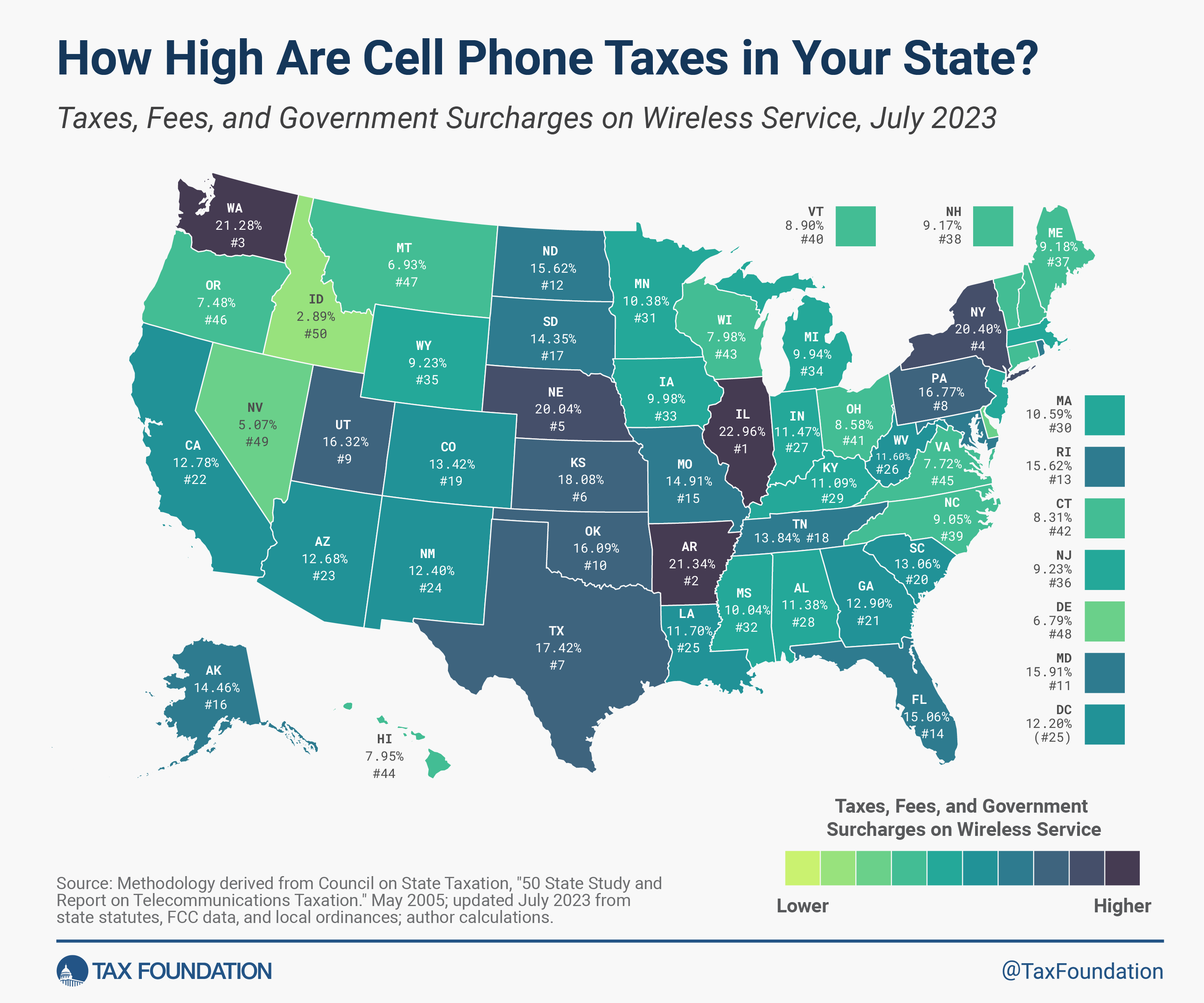

Table 2 ranks the states from highest to lowest in wireless taxes, fees, and government surcharges. Illinois has the highest wireless taxes in the country with state-local rates of nearly 23 percent on taxable voice services. Arkansas, Washington, New York, and Nebraska round out the top five states. Idaho, Nevada, and Delaware have the lowest wireless taxes in the nation. Figure 1 maps the states by state-local tax rates. High-tax states are distributed throughout the country, with the exception of the New England states, which tend to have lower rates.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

States have debated whether to expand the sales tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

from tangible goods to services for decades, with proponents of expanding the sales tax base to services arguing that the disparity in taxation between taxable tangible goods and exempt services does not make sense. When it comes to wireless services, however, the exact opposite is true. As shown in Table 3, wireless services are subject to state and local taxes 1.76 times higher than the sales taxes imposed on goods, with the average state and local wireless tax rate of 13.7 percent and the average combined sales tax rate at about 7.8 percent. In 16 states, wireless taxes are more than twice as high as sales taxes. Three states that have chosen not to impose a sales tax—Delaware, Montana, and New Hampshire—have special taxes on wireless and other telecommunications services.

Total Taxes Paid

Wireless consumers will pay about $12.6 billion in taxes, fees, and government surcharges to state and local governments in 2023 based on the tax rates calculated in this report. Less than half of this amount—$5.3 billion—represents state and local sales and use taxes. These taxes are broadly applied to taxable goods and some services and do not apply solely to wireless services. The remaining $7.3 billion are taxes that apply only to wireless and other telecommunications services. These taxes are discussed further in the next section of the report.

Appendix C provides a detailed breakdown of every tax, fee, and government surcharge imposed by state and local governments in each state. In many states, local government impositions vary by individual jurisdictions with some cities or unincorporated areas within a state imposing no taxes and others imposing very high taxes. To facilitate interstate comparisons, local rates in the most populated city and the capital city in each state are averaged into a single rate. For a more detailed discussion of the methodology in this report, please see Appendix A.

The Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act (PITFA) prevents state and local governments from imposing taxes on internet access services, including wireless internet access. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau suggests that more than half of all wireless service revenues are from internet access.[4] Without the protection of the federal law, the high excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections.

rates applied to taxable wireless services could be applied to internet access, and consumer tax burdens would be significantly higher.

State Trends in Wireless Taxes

911 and 988 Fees

Most states impose per line fees on telecommunications customers to fund capital and operating expenses for state and local emergency (911) systems. These fees vary significantly, from zero in Missouri to a high of $5.00 per line in Chicago.[5] In 2023, Nevada, New York, and West Virginia increased 911 fees while Connecticut and North Carolina reduced them. West Virginia now has the highest statewide wireless 911 fee at $3.64 per line per month.

In 2021, a new fee began appearing on customer bills in three states. The FCC mandated that a new three-digit number (988) be designated nationally to contact suicide prevention hotlines that will be operated in the states. A law passed by Congress authorized states to impose “988 Fees” to pay for some of the creation and operation of 988 crisis hotline centers. In 2021, Virginia was the first state to impose a new 988 fee of 12 cents per line per month. Colorado (18 cents per month) and Washington (24 cents per month) added new 988 fees in 2022. In 2023, Colorado and Washington both increased their 988 fees while California (8 cents per month) and Nevada (35 cents per month) added new fees. Delaware and Oregon also enacted new fees that will not take effect until 2024.

State Universal Service Funds

Twenty-two states impose their own “Universal Service Fund” (USF) charges on wireless services that provide subsidies for many of the same purposes as the FUSF. The federal government imposes a charge as a percentage of interstate revenues. States may also impose a state universal service surcharge on intrastate revenues , and most states with a state USF charge impose it as a percentage of intrastate revenues. However, some states have recently shifted to a flat per-line USF imposition. This shift has resulted in a large portion of the state USF burden being borne by wireless family share plans.

As detailed in Appendix Table B1, the highest per-line charge is in Oklahoma at $1.85 per line per month. A family with a share plan with four lines pays $7.40 per month ($89 per year) even if they have the lowest-price wireless plan. California became the latest state to impose a per-line USF charge, setting the charge at $1.11 per line in 2023. Other per-line state USF impositions are in Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, and Utah.

The remaining states continue to impose their USF charges on a percentage basis. Texas made headlines in 2022 when the Public Utility Commission approved a seven-fold increase in the state USF rate, from 3.3 percent to 24 percent of intrastate charges. A subsequent order reduced the rate to 12 percent of intrastate charges, which still resulted in a 350 percent increase in USF surcharges on wireless customer bills. As a result of this USF rate increase, Texas jumped to having the 7th-highest wireless taxes in the country in 2023 from 26th in 2022. In addition to Texas, other states with high state USF rates include Arkansas (8.3 percent), Kansas (7.2 percent), and Alaska (6.3 percent). In addition to Arkansas and Texas, other states that increased their USF surcharges in 2023 include Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. Kansas, Kentucky, Nevada, and Wyoming reduced their USF rates.

State Wireless Taxes

In addition to 911 fees, 988 fees, and state USF charges, 13 states impose wireless taxes that are either on top of sales taxes or in lieu of sales taxes but at a higher rate than the sales tax. Table 4 shows these states by type of wireless tax.

Local Wireless Taxes

Local governments throughout the country also impose taxes on wireless services that are not imposed on other goods and services. Many of these taxes are imposed because of legacy taxes that were established during the regulated telephone monopoly era that existed prior to the 1980s breakup of AT&T. Local governments in some states have longstanding authority to impose right-of-way (ROW) fees on telephone companies for placing poles, wires, and equipment on local property. In other states, localities impose franchise or license taxes on telephone companies in exchange for the privilege of doing business in a city.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when wireless services began to compete with wireline services, localities became concerned about losing revenues from local taxes on wireline telephone companies and sought to extend these taxes to wireless services. This occurred in some states even though wireless providers typically did not use the public right-of-way to place equipment or, when they did use public property (e.g., the tops of buildings), the usage was de minimis and paid for through negotiated rental agreements. This response to changing consumer behavior can also be observed in local taxation of streaming services and cable companies, where localities are fighting to retain revenue by attempting to tax streaming services as if they were using ROW like cable companies.[6]

Local governments in 14 states currently impose some type of tax on wireless services in addition to local option sales taxes. In most of those states, the taxes are additive and only further increase the tax burden on wireless services. California and Illinois are the exceptions—in these states, wireless services are subject to taxes in lieu of the sales tax, but in most cases, the wireless tax is higher than the sales tax. Table 5 provides a breakdown of the types of local wireless taxes that apply. Local taxes have a significant impact on the overall tax burden on wireless services in several of the states with the highest wireless taxes, including Illinois, Washington, Nebraska, New York, Utah, and Maryland.

California has the highest local taxes, with rates up to 11 percent. Washington follows closely with local taxes as high as 9 percent, followed by Illinois (up to 7 percent), Florida (up to 7 percent), and Nebraska (up to 6.25 percent). In addition to these percentage-based taxes, Illinois allows local per-line taxes of $5.00 per line in Chicago and Maryland allows Baltimore to charge $4.00 per line.

The Regressive Impact of Wireless Taxes

Economists use the term “regressive” to describe tax systems that impose higher tax burdens on low-income taxpayers than on higher-income taxpayers, as measured as a percentage of income. Low-income households spend a greater percentage of their budgets on wireless services than high-income households. Therefore, low-income households also spend a greater percentage of their budgets on wireless services taxes. Wireless services taxes are regressive.

The trend of increasing per-line impositions—for 911 fees, state USF surcharges, and even per-line general wireless taxes, along with the addition of 988 fees—makes wireless taxes even more regressive. Many consumption taxes have regressive effects, and while that is not in itself an argument against levying them, lawmakers should be cautious when increasing regressive taxA regressive tax is one where the average tax burden decreases with income. Low-income taxpayers pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while middle- and high-income taxpayers shoulder a relatively small tax burden.

burdens, particularly in the case of a targeted excise tax that does not meaningfully internalize any external harms and often far exceeds any amount necessary to pay for related government programs.

Excessive taxes and fees increase the cost of wireless services at a time when citizens are relying on them more than ever for access to government services (including education), health care, remote work, and commerce. In fact, wireless services are becoming the sole means of communication and connectivity for many Americans, especially those struggling with poverty. More than 76 percent of all low-income adults had wireless-only service and 68 percent of all adults were wireless-only.

Table 6 shows the impact of these high local taxes on wireless consumers in selected cities. In Chicago, a family of four paying $100 per month for taxable wireless services would pay about $34 per month (over $400 per year) in state and local taxes on wireless services. That same family in Baltimore would pay almost $340 in state and local wireless taxes annually.

Alternative Measures and Tax Comparisons

Wireless services provided to consumers have changed dramatically since this report was first published in 2003. When we first wrote the report, all components of a consumer’s typical wireless bill were subject to tax, including voice service, text messaging, data usage, and related ancillary services in most states. Today, however, most wireless plans include both taxable wireless services as well as non-taxable data plans used to access the internet. As previously discussed, the PITFA prohibits state and local governments from imposing any taxes on internet access.

This section of the report presents alternative measures of the tax burden on wireless consumers that account for the non-taxable internet access included in wireless plans. The average monthly revenue per wireless line is $34.56 per month. Of this amount, using Census Bureau data, about 53 percent of the typical bill is non-taxable internet access ($18.32 per month) and the remainder ($16.24 per month) is taxable wireless services.[7]

The first column in Table 7 ranks the states based on the total amount of state and local tax paid on a typical consumer’s bill. By this measure, Illinois still has the highest wireless tax burden in the country, with the typical consumer paying about $5.46 in state and local taxes per month. Column two shows the effective state and local tax rate as a percentage of the price paid for the taxable wireless services. Once again, Illinois has the highest tax burden with the typical consumer paying over one-third of the taxable portion in state and local taxes. The third column shows the effective state and local tax rate as a share of the entire bill, which includes both taxable and non-taxable services. Even including the non-taxable portion in the calculation, the effective state and local tax rate is nearly 16 percent in Illinois. Finally, column four shows the effective state and local tax rate using the COST methodology that has traditionally been used in this report.

The declining portion of taxable services may explain why more states have begun to rely more heavily on per-line taxes, fees, and government surcharges. For example, while most states have always imposed per-line 911 fees, more states are shifting their state USF impositions from a percentage of intrastate revenue to a flat per-line amount. California, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Utah have all recently made this change in the last few years and other states are considering it as well.

Under the alternative comparisons in Table 7, states that disproportionately rely on per-line taxes, such as Illinois, Maryland, and West Virginia, have higher overall tax rankings than states like California and Florida, which rely predominately on percentage-based taxes. By their very nature, per-line taxes are regressive and tend to burden lower-income wireless users more heavily than percentage-based taxes. They also burden families because most wireless providers charge less per line for each additional line added to a family plan. While family and lower-income wireless users bear a higher burden, consumers of higher-priced plans, generally business consumers, pay comparatively less on a percentage basis because the per-line taxes represent a lower relative cost to the price of their wireless plans.

The Economic Impact of Excessive Wireless Taxes

Policymakers should be cautious about expanding wireless taxes, fees, and government surcharges for two primary reasons. First, as discussed above, wireless taxes are regressive and have a disproportionate impact on low-income consumers. Excessive taxes and fees increase the cost of access to wireless services for low-income consumers.

Second, discriminatory taxes may slow investment in wireless infrastructure. Ample evidence exists that investments in wireless networks provide economic benefits to the broader economy because so many sectors—transportation, health care, energy, education, and even government—use wireless networks to boost productivity and efficiency. These economic benefits proved especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic because wireless networks helped employees work remotely and allowed students to continue their studies.

Network investment is important not only to consumers and businesses that use these wireless networks but also to the entire American economy. A report by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) surveyed the evidence from the United States and Europe as well as from the developing world. They consistently found that wireless infrastructure investment enables an entire entrepreneurial culture to focus on creating applications and devices to make businesses more productive and improve the lives of consumers. These tools in turn make businesses more successful so that they can create new jobs that generate economic activity and tax revenues for governments.

The ICC notes, “Remedying the discriminatory tax treatment of telecom goods and services may reduce tax receipts in the short-term, but the longer-term increase in the use of advanced capability devices, service demand, and network deployment resulting from these tax reductions is likely to counteract this loss of revenue over time.”[8] Policymakers need to weigh the trade-offs between the short-term revenue benefits of excessive wireless taxes and the long-term economic impact on the state from reduced infrastructure investment.

Applying the sales tax, a traditional broad-based consumption tax, is perfectly appropriate, but the excessive targeted taxation of wireless services lacks the traditional justifications—a “user-pays” system or the internalization of social costs—for excise taxation, raising consumer costs and undercutting investment in a vital market.

Conclusion

Wireless consumers continue to be burdened with high taxes, fees, and government surcharges in many states and localities throughout the country. Over half of the $12.6 billion in state and local taxes imposed on wireless services are discriminatory in nature, as they only apply to telecommunications services. These taxes disproportionately burden low-income Americans and disincentivize investment in new wireless services.

To alleviate the regressive impact on wireless consumers, states should examine their existing communications tax structures and consider policies that transition their tax systems away from narrowly based wireless taxes and toward broad-based tax sources that do not distort the economy and do not slow investment in critical infrastructure like wireless broadband.

Appendix

To access the methodology notes and tables, click the “Download PDF” and “Download Data” buttons at the top of this page.

References

[1] The program subsidizes telecommunications services for schools, libraries, hospitals, low-income people, and rural telephone companies operating in high-cost areas. The calculation of the Federal Universal Service Fund surcharge rate assumes that wireless providers use the “safe harbor” percentage. See Appendix B for a full explanation of the methodology.

[2] Figure includes watches, tablets, and other connected devices. Robert Roche, “CTIA’s Wireless Industry Indices Report, Year End 2022 Results,” July 2023, page 7.

[3] Stephen J. Blumberg and Julian V. Luke, “Wireless Substitution: Early Release Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July-December 2022,” National Center for Health Statistics, May 2023,

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, “Service Annual Survey Latest Data (NAICS-basis): 2021,” Nov. 22, 2022, Table 4,

[5] Missouri has no 911 fee on billed 911 service but does have a 911 fee on prepaid service.

[6] Ulrik Boesen, “Cutting the Cord from Cable Has States Courting New Revenue Streams,” Tax Foundation, Jul. 19, 2021,

[7] These figures are derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, “Service Annual Survey Latest Data (NAICS-basis): 2021,” Nov. 22, 2022, Table 4.

[8] International Chamber of Commerce, “ICC Discussion Paper on the Adverse Effects of Discriminatory Taxes on Telecommunications Service,” Oct. 26, 2010,

Share