Cargo loaders are exempt from the Federal Arbitration Act, but important questions remain

OPINION ANALYSIS

on Jun 7, 2022

at 9:47 am

Latrice Saxon, a cargo loader for Southwest Airlines, filed a federal wage-and-hour lawsuit against the company.

(rSnapshotPhotos via Shutterstock)

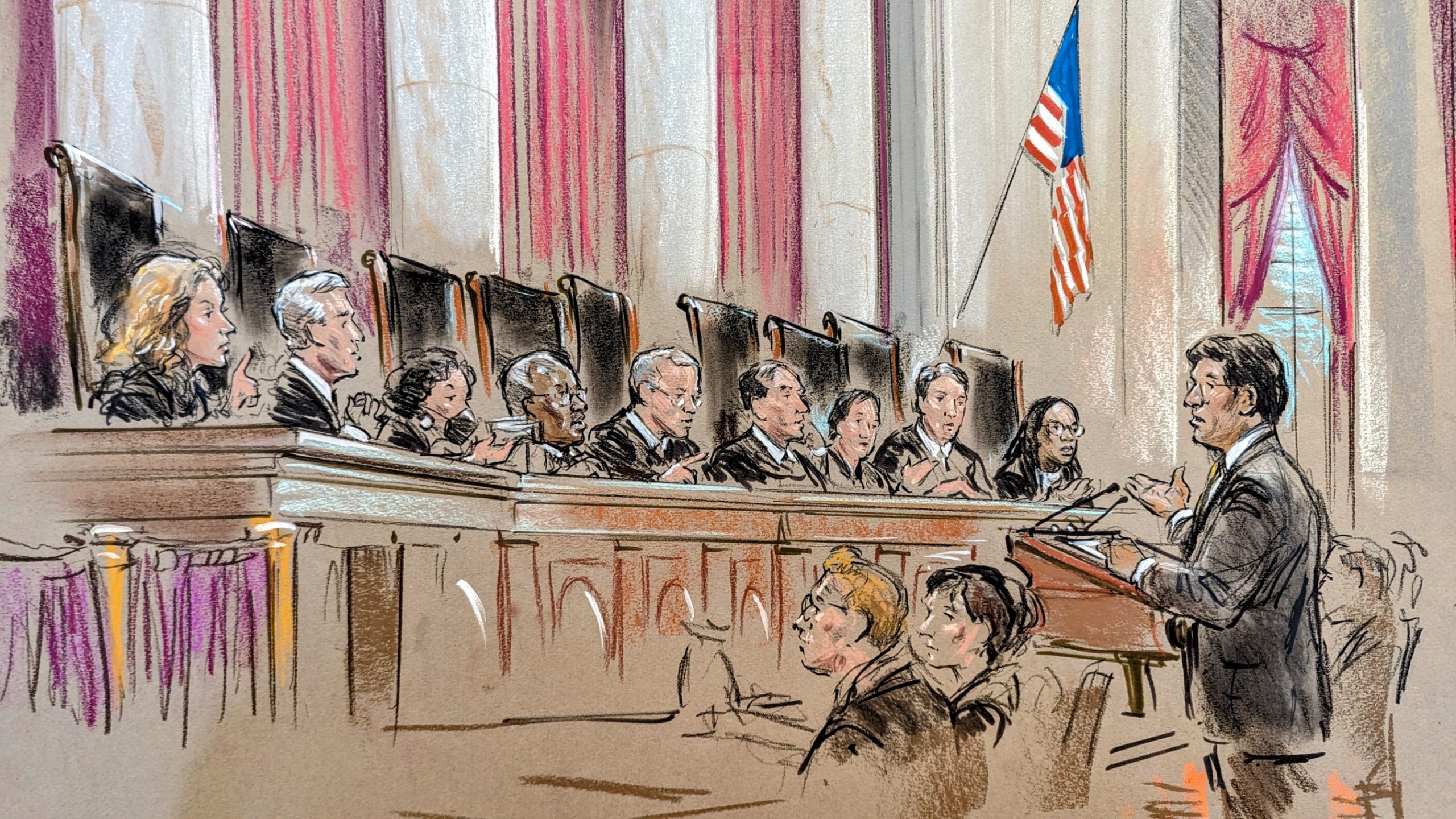

Latrice Saxon’s job includes loading cargo onto airplanes – but does that mean that she is part of a “class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce”? The answer to that question is significant because it controls whether or not Saxon and other workers who load cargo can be required under the Federal Arbitration Act to arbitrate their workplace disputes. On Monday, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for a unanimous court that Saxon does qualify as an interstate-transportation worker, meaning the arbitration agreement she signed is exempt from enforcement under the FAA. However, the opinion on behalf of eight justices — Justice Amy Coney Barrett was recused — left open other important questions about the scope of the FAA’s transportation-worker exemption.

This case began when Saxon, a Chicago-based ramp supervisor for Southwest Airlines, filed a federal wage-and-hour lawsuit against her employer on behalf of herself and others. In response, Southwest invoked the FAA, moving to stay or dismiss the lawsuit in light of Saxon’s arbitration agreement. The FAA requires courts to enforce most arbitration agreements, and the Supreme Court has previously concluded that this requirement generally includes arbitration clauses that appear in employment contracts. However, the FAA also contains an exemption: It does not apply to “contracts of employment of seamen, railroad employees, or any other class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce.” Saxon was plainly not employed as a seaman or railroad employee, setting up the question of whether ramp-agent supervisors — who load and unload cargo in addition to their supervisory duties — fall under the residual clause.

The court broke its relatively concise analysis into two parts: First, it determined the “class of workers” to which Saxon belonged; then it analyzed whether that class of worker was “engaged in foreign or interstate commerce.” To answer the first question, the court focused on Saxon’s job duties, writing that she “belongs to a class of workers who physically load and unload cargo on and off airplanes on a frequent basis.” Next, the court turned to whether cargo loaders were “engaged in foreign or interstate commerce,” asking whether they were “directly involved in transporting goods across state or international borders.” Relying in part on cases from around the time the FAA was enacted, the court reasoned that cargo loading was understood to be “intimately involved” with moving goods across state lines. In addition, the court observed that the FAA refers to “agreements relating to wharfage” as “matters in foreign commerce,” which is significant because wharfage agreements included those “for mere access to a wharf — which is simply a cargo loading facility.” In other words, the reference to wharfage agreements is further evidence that Congress saw cargo loading as part of “foreign commerce.”

In reaching its conclusion, the court rejected a broader approach that Saxon had urged — specifically, that the relevant “class of workers” was all or nearly all airline workers, including, for example, ticket-takers or website designers. Here, the court began from the premise that the transportation-worker exemption’s enumerated categories — seamen and railroad employees — must share a common attribute with each other and then with the residual clause. But “seamen” did not include the entire maritime industry; the court concluded that it encompassed only workers whose occupations included “work on board a vessel.” Therefore, the “common attribute” between seamen and railroad employees could not be “identifying transportation workers on an industrywide basis.”

Using similar reasoning, the court also rejected Southwest’s preferred approach, which was that only workers who accompanied goods across state or national borders fell within the transportation-worker exemption. Here, the court focused on “railroad employees,” a term that was not limited to workers who travelled across state lines. Further, the court rejected the airline’s attempt to analogize to cases about activities with more distant connections to interstate commerce, such as providing janitorial services to a company that was engaged in interstate commerce. Finally, the court also rejected the FAA’s generally pro-arbitration purpose as a reason to construe the transportation-worker exemption to exclude cargo loaders.

After this decision, the FAA will not be an impediment to cargo loaders’ abilities to litigate their employment disputes. But this case is not going to be the last word on the scope of the transportation-worker exemption, which is hotly disputed in cases involving workers who play other roles in transporting goods or passengers. Citing cases involving Amazon last-mile delivery drivers and Grubhub drivers, the court noted only that “the answer will not always be so plain” as in this case. In other words, the lower courts will undoubtedly continue to wrestle with the scope of the transportation-worker exemption.