Build a Consumer Base with Innovation; Protect Sales with Design Patents

“Design patents have a unique value within online markets where pictures of products—i.e., ornamental appearances—are ubiquitous and many different groups may be engaged in infringing activities in that same online market.”

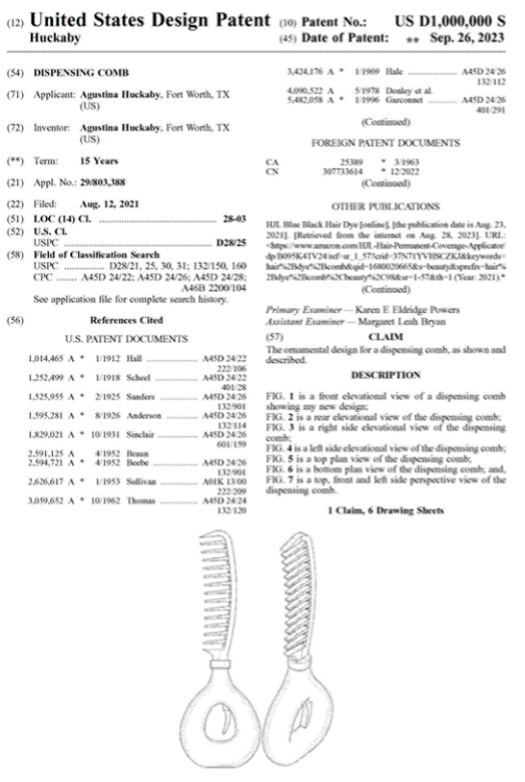

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issued its one millionth design patent on September 26, 2023. U.S. Patent No. D1,000,000 claims the ornamental design for a dispensing comb:

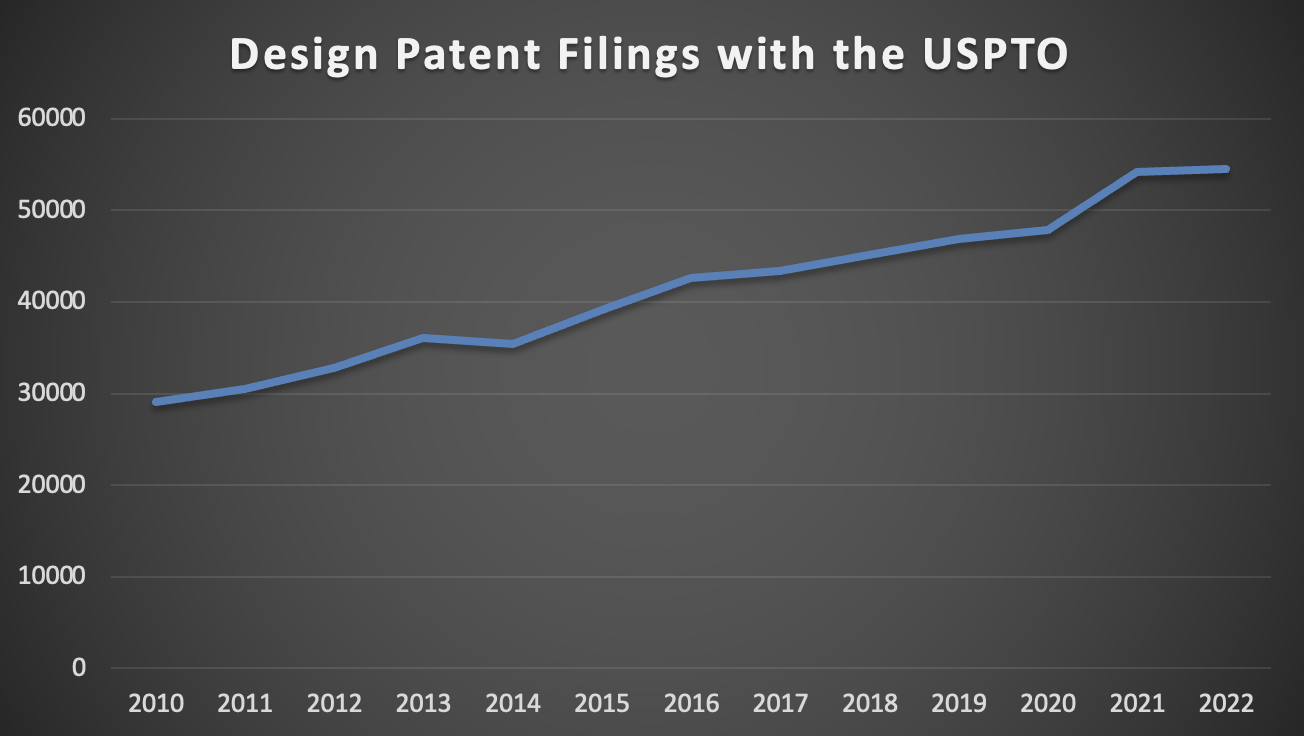

This milestone comes during a particularly prolific period for design patents. In 2022 alone, the USPTO received more than 50,000 design patent applications. The Office has seen a 20% growth in design patent applications over the last five years.

It is not hard to understand why inventors are seeking design patent protection at previously unseen levels. In an age of complicated technologies, design patents can protect marketable appearances of products in the same manner generally as trademarks identify source. Understanding design patent benefits underlying the recent growth in application numbers is a good lesson for businesses seeking to distinguish a brand—but keep an eye out for further developments and be prepared to adjust business and IP strategies. We touch on each below.

The relatively straightforward (that is not to say “simple”) nature of design patents as protecting the ornamental design visually depicted in a set of drawings is simple to present. A design patent application requires only a single claim defining the patented design with reference to the drawings and typically the brief description of the drawings constitutes the vast majority of the specification. While utility patent claims protect functional components and processes, often in highly technical language subject to protracted battles over interpretation, the test for design patent infringement remains whether an “ordinary consumer” would purchase an infringing product, believing it to be the patented article. Still, despite the rise in the number of design patent applications the number of design patent infringement cases filed per year has remained generally the same for at least the past five years. It will be interesting to see what happens to that figure as more and more steadily increasing design patent applications proceed to grant.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of design patent applications has also overlapped with Amazon’s introduction of procedures for receiving and investigating allegations of IP infringement occurring within the Amazon marketplace. Design patents have a unique value within online markets where pictures of products—i.e., ornamental appearances—are ubiquitous and many different groups may be engaged in infringing activities in that same online market.

In much the same manner as trademarks protect goodwill in a product with a trusted source, a design patent may be a powerful tool for removing unauthorized product offerings and online sites. But do not underestimate the level of complexity or damages in design patent infringement cases, especially in the case of high-tech—high-sales figures—products.

Design Patents at the Center of High-Stakes Disputes

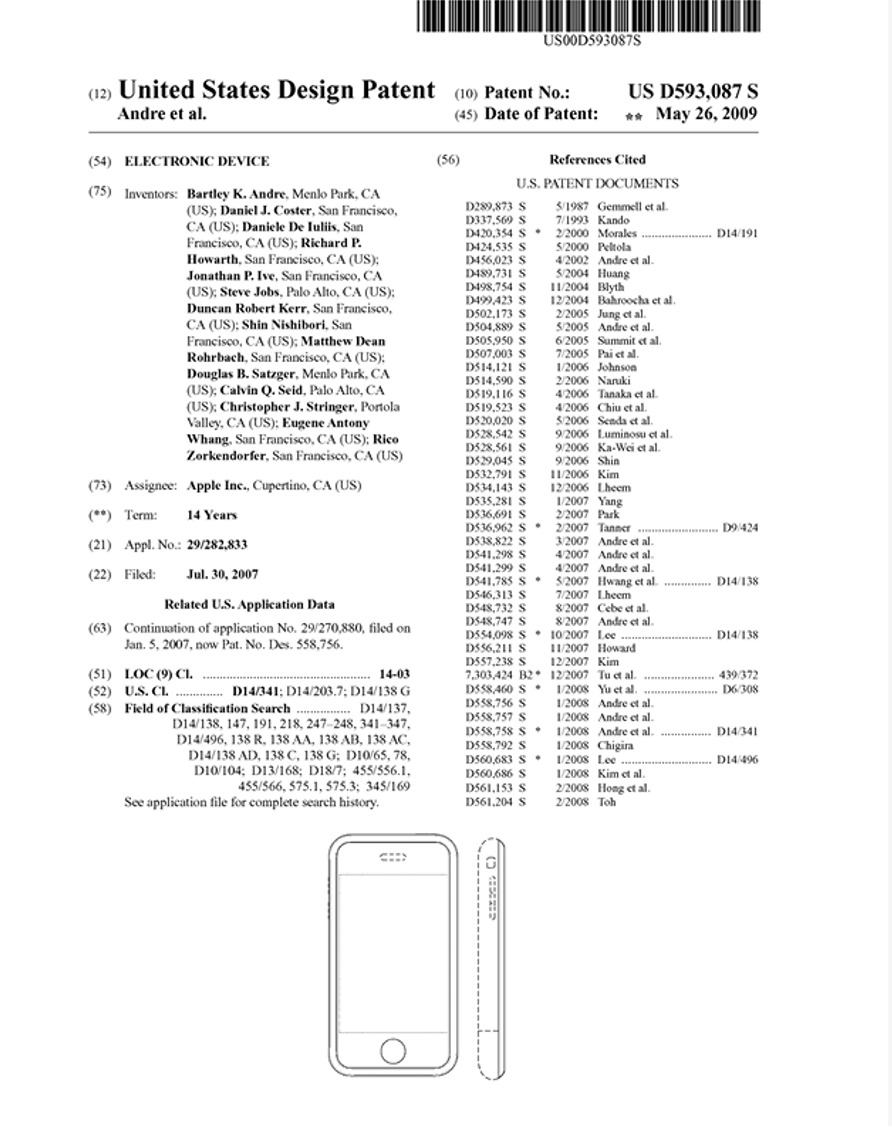

In perhaps the most famous example of a design patent covering high-tech gadgets, Apple’s more than $1 billion verdict against Samsung in 2012 included a finding that Samsung infringed Apple’s patent covering the iconic iPhone’s appearance—including rounded corners and a single, circular button at the bottom of the front face:

Even at the time of Apple v. Samsung, a single smartphone could incorporate hundreds of features and functions individually covered by hundreds of utility patent claims. Identifying infringing devices is no small feat when a utility patent claim covers, for example, software-based handoff procedures for mobile electronics traveling between radio towers. And jurors—or at least most jurors—will not likely have existing background and fluency in the technical claim language.

Add that patentees are their own lexicographers and a utility patent specification may define a claim term differently than even jurors with a proper background expect. Design patents then become an appealing option for protecting an innovation, not for what it does or what it “comprises,” but for the product appearance that consumers—and likely jurors—associate with the innovation.

In other words, a consumer’s loyalty to iPhone may be due to technical features such as the operating system, antenna and battery efficiency, graphical user interface (GUI), etc., but the consumer’s purchase of the newest iPhone requires clearly identifying the iPhone based on its patented ornamental design. The consumer trusts that an iPhone having Apple’s patented design will have the iPhone technical features.

Design Patent Obviousness Changes Under Consideration

The one millionth issued design patent comes on the heels of a design patent milestone case at the Federal Circuit. On June 30, 2023, the court agreed to hear a case en banc for the first time in over five years (since Aqua Products, Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017)).

As has been reported on IPWatchdog previously, the full panel of the Federal Circuit will decide in LKQ v. GM whether to square the test for design patent obviousness with KSR’s approach for utility patents, among other questions. According to appellants, KSR’s holdings are equally applicable to design patent obviousness and the Federal Circuit should square design patent obviousness—currently evaluated by a two-part test sometimes called the Rosen-Durling test—with the rigid approach in KSR.

Under the Rosen-Durling test, first, a suitable primary reference must be identified, “the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design.” Second, “other ‘secondary’ references ‘may be used to modify [the primary reference] to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.’” However, “secondary references may only be used to modify the primary reference if they are ‘so related [to the primary reference] that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.’”

The fundamental question with which the Federal Circuit must wrestle is whether design patents and utility patents are really so different that they require different obviousness standards, and if not can the Rosen-Durling test be squared with KSR? Most amici have warned against making changes to the existing test, with Apple citing the dangers in altering the framework on which “design-focused industries have relied for decades.” The Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) has similarly called any modification to the Rosen-During test “undesirable and unnecessary.” The IPO further argued that if the Court determines a change is necessary, any change should not be whole-scale, but instead the standard should be tweaked based on the decades-old obviousness framework in Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 383 U.S. 1 (1966), as informed by Whitman Saddle and other appellate cases that laid the framework for the Rosen-Durling test.

The only thing that is clear is the lack of clarity that would result from any change to the Rosen-Durling test that has long been in place. It would almost certainly lower the standard for identifying a primary and combinable secondary reference, but without guidance as to what the new standard would be, planning is difficult. There is little the industry can do but wait.

The court’s decision in LKQ v. GM is expected in 2024.