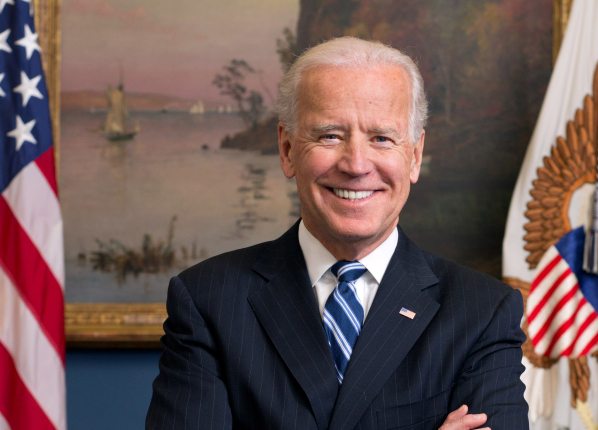

Biden Reportedly Considering Executive Action on Border Crisis

News reports suggest that President Biden is considering taking some sort of “executive action” in response to the crisis his policies have created at the Southwest border. This isn’t exactly news — CNN reported last February that the White House was mulling over an unspecified proposal to “deport[] non-Mexican migrants to Mexico in an unprecedented step to stem the flow of migration”, but the rapid collapse of the Senate border bill coupled with polling that shows illegal immigration is fast becoming a political liability has apparently prompted the administration to float some new ideas. I’ll believe it when I see it, because Biden’s Justice Department doesn’t appear to be on board — and a circuit court judge just called the administration out on it.

“President Biden Is Considering Executive Action.” It’s not clear exactly what the administration is considering, but the New York Times has reported that: “President Biden is considering executive action that could prevent people who cross illegally into the United States from claiming asylum.”

That’s interesting — but hardly novel — because nine months ago the administration rolled out new regulations that, in essence, were supposed to do the same thing.

Those regulations, formally captioned “Circumvention of Lawful Pathways” (abbreviated by my colleague George Fishman as the “CLAP rule”), were published in the Federal Register by DHS and DOJ on May 16, backdated to May 11 — the day Title 42 ended.

The CLAP rule, however, had its genesis in a January 5, 2023, White House fact sheet titled “Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Border Enforcement Actions”, which explained:

When Title 42 eventually lifts, noncitizens located in Central and Northern Mexico seeking to enter the United States lawfully through a U.S. port of entry have access to the CBP One mobile application for scheduling an appointment to present themselves for inspection and to initiate a protection claim instead of coming directly to a port of entry to wait. This new feature will significantly reduce wait times and crowds at U.S. ports of entry and allow for safe, orderly, and humane processing.

I have referred to that port processing plan as the “CBP One app interview scheme”, and there are any number of misstatements in that pronouncement, beginning with the fact that the scheme didn’t start “when Title 42 eventually lift[ed]” but instead went “live” — as CBP put it — a week later.

And although the White House claimed that illegal aliens would be using the CBP One app to make appointments “to initiate a protection claim”, CBP was quick to note it “does not adjudicate asylum claims”.

Instead, as a CBP One release explained: “Individuals issued a Notice to Appear and placed in removal proceedings will have the opportunity to seek relief, including asylum, or other protection before an immigration judge.”

By the end of April 2023, CBP reported that more than 79,000 inadmissible aliens had used CBP One to schedule interviews at the Southwest border ports. And then, just over two weeks later, the CBP One app interview scheme was officially implemented in the CLAP rule.

The CBP One app interview scheme was just one part of that rule, which imposes a rebuttable presumption that illegal aliens who failed to seek asylum on the way here aren’t eligible for protection.

That “rebuttable presumption” is not absolute, however. There are three exceptions: one for aliens who scheduled port appointments using the CBP one app, a second for those who applied unsuccessfully for asylum elsewhere, and a third for those who tried and failed to use the app.

Even then, migrants can rebut that presumption by showing they have an acute medical emergency, “faced an extreme and imminent threat to their life or safety, such as an imminent threat of rape, kidnapping, torture, or murder”, or were victims of trafficking.

Those exceptions and evidentiary rebuttals aside, that sounds more or less like what the Times reported the White House is considering. Except there’s nothing “new” about it.

M.A. v. Mayorkas. That’s not the end of the story, however. On June 23, 2023, a group of migrants and advocates filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, challenging implementation of the CLAP rule as it related to those who, in lieu of using the CBP One app to schedule interview appointments at the ports, entered illegally.

That case is entitled M.A. v. Mayorkas, and here’s how the National Immigrant Justice Center (“NIJC”, which joined the ACLU and other groups in the matter) describes that litigation: “This lawsuit challenges the Biden administration’s sweeping asylum ban and several new expedited removal policies that dramatically alter the screening interview process for asylum seekers and wrongfully return many back to persecution and grave danger.”

That’s not how I would describe the CLAP rule, but regardless, you’d be forgiven for not knowing that the Biden administration had imposed a “sweeping asylum ban”, because the CLAP rule hasn’t had much effect on illegal immigration at the Southwest border.

In September, the plaintiffs in M.A. filed a motion for summary judgment, which Biden’s DOJ followed up on with its own cross motion for summary judgment in October.

But then, on February 5, both parties — the plaintiffs and DOJ — filed a “Joint Stipulation to Hold Case in Abeyance”.

That motion essentially asked the court to sit on the matter for 60 days, explaining in pertinent part:

The parties are engaged in discussions regarding implementation of the challenged rule and related policies and whether a settlement could eliminate the need for further litigation, and the parties believe an abeyance will facilitate such discussions. … Finally, the government has agreed not to remove any of the noncitizen plaintiffs currently present in the United States pending resolution of their claims.

East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Biden. M.A. was not the only challenge to the CLAP rule. In May, plaintiffs who had been challenging border policies implemented by the Trump administration (that I’ll discuss below) in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Biden filed an amended complaint to also challenge the CLAP rule.

On July 25, 2023, the district-court judge in that matter vacated and remanded the CLAP rule but stayed his order for two weeks to enable the Biden administration to seek further review from the Ninth Circuit. As my colleague Elizbeth Jacobs reported in August, a divided Ninth Circuit panel granted DOJ’s request to stay the judge’s order, while setting the matter for an expedited hearing.

Here was NIJC’s take on that case after the circuit court’s order:

The Biden administration ban largely mimics two Trump-era policies — known as the “entry” and “transit” bans — which were previously blocked by federal courts. It prohibits asylum for everyone at the border who transited through another country en route to the United States (i.e., people from countries other than Mexico) except for those who are able to obtain a scarce appointment to present themselves at a border port through a flawed mobile application; the rare person who first sought and was denied asylum in another country; or those who can prove that they qualify for one of a few other extremely narrow exceptions.

I’ll note that CBP expanded the number of Southwest border port app appointments available daily from 1,250 per day to 1,450 per day in June (more than a half-million per year), which I’d hardly term “scarce”. That’s especially true given congressional disclosures that reveal nearly 96 percent of aliens who use the app to schedule appointments at the ports are then paroled into the United States.

In any event, the parties in East Bay also filed a joint motion to hold the government’s appeal in abeyance pending settlement negotiations in that case and M.A., which the Ninth Circuit panel — on a divided two to one vote — granted on February 21.

“The Administration and Its Frenemies on the Other Side of this Case”. The odd judge out was a Trump appointee, circuit Judge Lawrence Van Dyke, and he didn’t pull any punches in his dissent:

After the plaintiffs brought this case to enjoin and vacate the rule, the federal government spent the better part of a year vigorously defending the rule’s critical necessity before the district court and in this court — all because, in the government’s words, “any interruption in the rule’s implementation will result in another surge in migration that will significantly disrupt and tax DHS operations.”

…

Taking the government at its word about the pressing need for this crucial rule to remain in effect and be enforced, our court granted a stay of the district court’s decision enjoining the government’s rule. We heard oral argument and are now poised to render our decision. Then suddenly, out of the blue, the parties come to us hand-in-hand, jointly asking us to hold off making a decision while they “engage[] in discussions regarding the Rule’s implementation and whether a settlement could eliminate the need for further litigation.” For months, the rule was so important that “any interruption” in its implementation, even for a short period of time, would incapacitate the executive’s border response. This panel made decisions based on those representations. Now, the government implies the rule isn’t so important after all. Indeed, the government is now “engaged in discussions” that could result in the rule going away. What?

The administration’s abrupt about-face makes no sense as a legal matter. Either it previously lied to this court by exaggerating the threat posed by vacating the rule, or it is now hiding the real reason it wants to hold this case in abeyance. Given its success thus far in defending a rule it has consistently characterized as critical to its control of the border, and the fact that it has to realize its odds of success in this case can only improve as it works its way vertically through the federal court system, the government’s sudden and severe change in position looks a lot like a purely politically motivated attempt to throw the game at the last minute. At the very least it looks like the administration and its frenemies on the other side of this case are colluding to avoid playing their politically fraught game during an election year. [Emphasis added.]

“Sue and Settle”. A November 2021 Wall Street Journal op-ed derided the Biden administration’s reported plans to pay $450,000 a piece to migrant children who had been separated from their parents during the Trump administration.

Those so-called “family separations” were a key talking point for then-candidate Joe Biden during the 2020 presidential election, and Peter Wallison, author of the piece, complained that those payments were just another example of what he termed “sue and settle”. He explained:

In these cases, an organization or group would sue the government for some alleged wrong. The suit would wind on for a while, and then the Justice Department would announce that it had been settled, with a generous payment to the allegedly aggrieved party. Sometimes companies and groups would get portions of the settlement, even though they had not actually suffered any injury or were not even parties to the original suit.

What Judge Van Dyke is complaining about is a variation on sue and settle, under which (here) the Biden administration promulgates a “tough” border policy unpopular with its base; outside groups sue; and even though DOJ litigates the case, it ultimately agrees to a settlement that not only undoes the policy but also creates precedent that will make it more difficult for a future administration to implement a similar or tougher policy.

As Judge Van Dyke himself posits:

the executive may once again be trying to insulate bad Ninth Circuit caselaw from Supreme Court review. As I and others have previously written, our East Bay precedents are clearly wrong. … Yet they aided the Democratic cause by invalidating Trump-era immigration rules. If this case gets before the Supreme Court, the safe bet is that it would overrule those erroneous precedents. This settlement tactic is therefore a powerful tool for the administration: it lets it perpetuate bad — but politically favorable — law in the Ninth Circuit by settling before reaching the Supreme Court, and then throw up its hands and say it is bound by that law. [Emphasis added; internal citations omitted.]

212(f). Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) and others (including me) have argued that the president doesn’t need any new congressional powers to secure the border, but can instead use his authority under section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to suspend the entry of illegal migrants, and is failing to do so.

Critics usually respond by saying that the Trump administration already tried to use that power to bar illegal migrants, but was prevented from doing do by the courts. Guess which case they’re referring to? I’ll let CNN explain it:

In 2018, Trump tried to use 212f, which gives the president broad authority to implement immigration restrictions to restrict border crossings. But ultimately, a federal appeals court ruled that the authority conflicts with asylum law and the 212f authority doesn’t override it.

The case — known as East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Trump — served as an example of why the president is limited in his ability to shut down the border. It’s likely to face legal challenges if the White House were to move forward with it. [Emphasis added.]

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district-court judge’s injunction in East Bay of that Trump rule in February 2020, but it wasn’t until March 2021 — after Biden took office — that the Ninth Circuit denied an earlier-filed motion for rehearing en banc (by a larger circuit panel in the Ninth Circuit). Biden’s DOJ could have sought review of that decision by the Supreme Court; it didn’t.

I’m not saying the administration isn’t being earnest in claiming it’ll take executive action to secure the border, nor am I saying Biden’s Justice Department isn’t vigorously litigating challenges to his prior border actions. But that seems to be what at least one Ninth Circuit judge thinks may be happening.