Antitrust and Crypto Exchanges: Time to HODL (Part 2)

Network effects could drive concentration among crypto exchanges

Competition can take many forms. Some markets sustain a large number of firms operating and growing in parallel. In other markets, the competitive process leads to all (or almost all) rivals being eliminated, save for one or a small number of survivors. This latter case has come to be known as a ‘winner-takes-all’ or ‘tipping’ scenario, where the competition takes place ‘for’ the market; not ‘within’ it. Understanding the role of network effects is critical to understanding what type of competition to expect from crypto exchanges; specifically, (i) whether the sector is characterized by network effects, (ii) how strong any such network effects are, and (iii) what the initial data suggest.

Is competition among exchanges characterized by network effects?

Network effects – more specifically, direct network effects – occur when the value of a service to one user depends on how many other people also use that service. Take messaging apps or social networks. These services only have value to me if my friends and family use them too. My ‘network’ would otherwise be a lonely (and distinctly un-social) place. The more users a network has, the more value it provides. This concept is neatly summarized in Metcalfe’s law: the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users connected to the system.

In economic theory, while network effects help increase the value of a product (e.g., a telephone system, a social network), they can also act as a barrier to new firms entering or expanding, and lead to markets ‘tipping’. How do I convince Janet to use my social network if Jim, Jemima, and all of her other friends use a different one? The same problem affects trading venues. Buyers and sellers of financial instruments – stocks and shares, bonds, repo contracts, or commodities futures – want to trade on exchanges where lots of other buyers and sellers are present. The larger a venue’s user base, the greater my chance of finding a counterparty who is willing to accept the price at which I am hoping to buy or sell. As noted above, this dynamic is reflected in the size of the ‘spread’. The more successful an exchange has been in matching up buyers and sellers, the better chance a trader has in buying or selling at their preferred price.

How does this affect competition among exchanges? In principle, it means that buyers and sellers of a financial instrument will congregate on one or a small number of exchanges, giving those exchanges a potentially powerful market position. It may also make it difficult for rival platforms to enter or expand once an incumbent has an established position. And it means that there can be a substantial ‘first mover’ advantage. While entry is not impossible, rivals cannot realistically enter or expand by competing for one trader or investor at a time; they need to convince a critical mass of users to move over in order to overcome the network effects protecting the incumbent. The presence of network effects – and the resulting barriers to entry – has been observed in traditional financial and commodities exchanges. The UK Competition and Markets Authority, in its review of the Intercontinental Exchange/ Trayport merger, noted that:

“Liquidity pools tend to be self-reinforcing; that is, the more people that trade on a single venue the greater the liquidity and the more people who will come to that venue to trade. These network effects are an important feature of the wholesale energy trading markets.

As a result of network effects, the value of the services offered by trading venues increases with the number of market participants that use that venue. To some extent, this can make liquidity ‘sticky’ and it prevents traders from easily switching between venues and/or clearinghouses because doing so will risk losing access to the highest liquidity and, therefore, best prices available.

[…]

As OTC markets become more liquid the products concerned become more suitable for exchange-based trading. Accordingly, exchanges develop vanilla or copycat products and compete to become the first exchange on which liquidity gathers, including by offering fee holidays, discounts and rebates. Given the importance of network effects and the stickiness of liquidity once it has gathered on a venue, the time to market and first-mover advantage is an important competitive factor.”

Similar observations have been made in the European Commission’s reviews of potential concentrations among trading venues for traditional financial instruments. These dynamics are also present in competition among crypto exchanges, where liquidity is a core parameter of competition. Those with the most users can offer the narrowest bid-ask spreads, which in turn may attract more users in a self-reinforcing cycle. This cycle may be strengthened if users – rightly or wrongly – perceive larger exchanges as being more stable and secure.

How strong or weak are network effects as a barrier to entry or expansion?

The mere existence of network effects does not mean that a market is bound to tip towards one or a small number of players. What matters is the strength of network effects, which can increase or decrease depending on a range of factors.

Multi-homing. Investors using multiple platforms in parallel – known as ‘multi-homing’ – can dampen the strength of network effects and reduce the likelihood of a ‘winner takes all’ form of competition. There are ample examples of digital services that are characterized (to some degree) by direct or indirect network effects, but where multiple services continue to compete and grow in parallel, in part due to multi-homing. Consider price-comparison websites, rideshare services, messaging apps, and collaborative working tools. In the case of crypto exchanges, it is difficult to know how prevalent multi-homing may be. On the one hand, investors may choose to trade exclusively on the platform that offers the most favourable (i.e., narrowest) bid-ask spread, or the best level of security. On the other hand, investors may prefer to spread their funds across multiple exchanges as a hedge against any single exchange going out of business.

Differentiation. Network effects can also be dampened where platforms differentiate their services, leading users to multi-home or attracting different groups of users who prioritise different features. Returning to the example of messaging services, many users may be content to rely on iMessage, WhatsApp, or other tools for their day-to-day conversations, but use tools like Telegram for privacy-sensitive communications, in view of Telegram’s apparent focus on security. Crypto exchanges may likewise seek to differentiate by focusing on particular countries or regions (e.g., bitFlyer in Japan), focusing on ease of use, or listing rare coins. As one commentator put it: “Am I looking for something like Casa, because Casa does a lot of work for me and I don’t have to worry about a public and private key? Am I going to Gemini, because Gemini has this weird coin that I want and they’ll allow me to buy it? Or am I going to Coinbase because Coinbase has these really cool tools that allow me to learn and earn crypto?” Exchanges may also differentiate by listing tokenized (non-crypto) assets such as art, real estate, or copyrights in musical works, as discussed above.

Unravelling. Even strong network effects do not necessarily ensure an entrenched market position for the leading players. Network effects can cause a particular platform to scale up rapidly, in a virtuous circle where winning one user leads to winning more users. For the same reason, though, network effects can also cause platforms to quickly unravel, where the loss of some users decreases the platform’s utility for the remainder, leading more users to abandon it in turn. Unravelling can be brought about by a variety of factors – setting unduly high prices, loss of quality, or external shocks that affect some platforms more than others. For example, regulatory requirements in South Korea – including an obligation on crypto exchanges to partner with local banks – led to just four centralized exchanges remaining available to service Korean consumers; approximately 60 crypto exchanges could not comply and exited the market. This type of shock can upend existing hierarchies where leading players find themselves severely constrained in their ability to operate, causing user defections.

Dynamic disruption. Citing academic texts, the UK Competition Appeal Tribunal has identified ‘dynamic competition’ as entailing “the introduction of new products and new processes” which “does not merely bring price competition” but “tends to overturn the existing order”. While that definition is far from clear-cut, DEXs could plausibly be seen as a dynamic rival to centralised exchange. As described above, DEXs offer a different process for trading coins and tokens relative to centralised exchanges – in particular by removing a centralised intermediary, providing automated market-making to the benefit of longtail coins and tokens, and allowing for flexibility in what level of commitment investors wish to make. DEXs have increased in popularity and may be seen as a serious dynamic threat to centralised exchanges – in at least one case, a centralized exchange has even converted to a DEX structure.

What does current market data suggest?

Many centralized crypto exchanges currently operate around the world, competing for users along these parameters. CoinMarketCap maintains a list of over 300 exchanges, ranking them by trading volume. Other analysts report the existence of even more exchanges when DEXs, brokers, and crypto derivative platforms are taken into account. The specialist press is replete with varying recommendations of the best platforms for crypto trading.

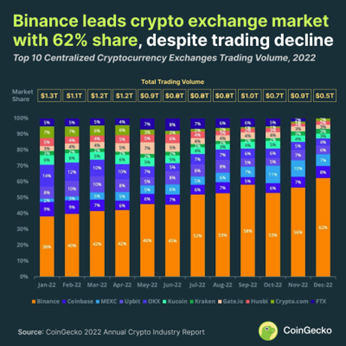

There are indications, though, that the largest centralised exchanges are pulling away from their rivals. Binance reportedly accounted for approximately 30% of all ‘spot’ transactions (i.e., users buying or selling cryptocurrencies) on centralized exchanges in March 2022 and more than half of all derivatives trading. By August 2022, Binance’s share of spot transactions had grown to approximately 55%. As of December 2022, Binance’s share had reportedly grown to 62% and captured more of the now-defunct FTX’s activity compared to other exchanges, as shown in Figure 4. Thus, a CryptoCompare report predicts that “as the industry matures, we expect there to be an oligopoly of exchanges dominating trading volumes as their traction accelerates and smaller players are left behind”.

Figure 4: Share of spot transactions across centralized exchanges (2022)

Economic or regulatory shocks may also shorten the ‘long tail’ of crypto exchanges. Economic theory posits that market downturns can ‘shake out’ weaker players, leaving behind only those firms that are robust enough to survive in the longer term. The crypto sector is characterised by faster and more intense downturns (and upturns) than many others.

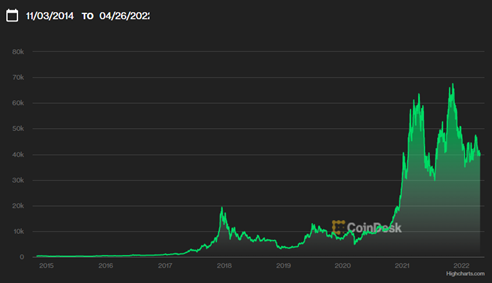

For example, between November 2021 and January 2022, the value of a single Bitcoin fell from approximately $67,000 to $36,000, necessarily affecting revenues for crypto exchanges. This price volatility is reflected in Figure 5 and has been attributed to a range of factors, such as (i) interest rate changes, with lower rates fuelling investments in perceived ‘risky’ crypto assets before the rate rises prompting a sell-off; (ii) crypto’s novelty as an asset class, with limited adoption as an everyday currency; (iii) Bitcoin ‘whales’ selling large amounts of bitcoins onto markets, particularly when this sets off chain reactions by trading bots linked to crypto derivatives; (iv) regulatory uncertainty; and (v) limited liquidity as investors hold onto their cryptocurrencies while waiting for current political and regulatory uncertainties to play out.[22]

Figure 5: Bitcoin-to-USD Exchange Rate

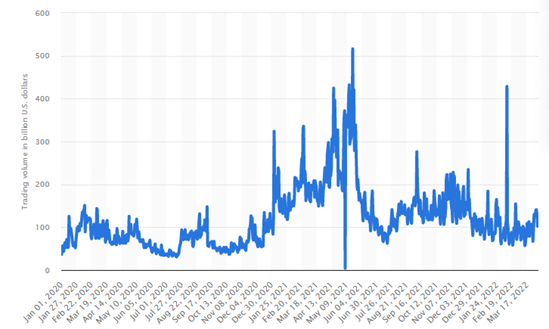

These shocks – and the underlying factors that may cause them – necessarily affect the value of crypto exchanges too, at least in the short term. Trading volumes on crypto exchanges are accordingly susceptible to rapid increases and declines.

Figure 6: Overall Cryptocurrency 24h Trade Volume

Of course, the mere fact of some crypto exchanges pulling ahead of the rest does not necessarily mean that the market will ‘tip’; it could be a short-term trend or a trend that is liable to be disrupted by regulatory shocks, technological developments, mergers among long-tail players, the ‘rapid instability’ of platforms characterized by network effects, and other factors. And it remains to be seen whether regulatory or relationship shocks may, in fact, disproportionately affect larger players. For example, reportedly in response to pressure from the UK Financial Conduct Authority, Binance’s UK banking partner (Paysafe) would terminate the companies’ partnership, causing Binance to suspend withdrawals and deposits in GBP.

But, taken together with the economics of network effects, current trends towards consolidation suggests that a ‘winner takes all’ market is at least possible, albeit too soon to reach a firm conclusion.

Antitrust scrutiny of crypto exchanges is coming

It seems almost perverse to write about antitrust intervention and crypto exchanges in the same sentence. Antitrust tends to intervene in markets that are well-established, characterized by players with market power, and where competition has become slow and soft. But cryptocurrencies have been around for barely a decade. Crypto offers a nascent alternative to fiat currency, which still accounts for the vast majority of payments worldwide. The crypto sector is dynamic, with new players entering the space seemingly every week, and with exciting offshoots, such as tokenization of illiquid assets. And a core achievement of crypto – on one view – is to decentralize, cutting out entrenched intermediaries. Surely, crypto belongs at the very bottom of the antitrust to-do list.

Yes and no. It may be some time until officials from antitrust agencies come knocking at the doors of crypto firms, but come they will, and sooner than one might think. As described above, the dynamics of competition among crypto exchanges could conceivably play out in a winner-takes-all scenario, driven by first-mover advantage, network effects, and users crowding in to those exchanges perceived as being the safest. Moreover, the largest crypto exchanges appear to be establishing a commanding lead over the remainder. While these issues are far from certain and would require an in-depth review of the evidence and data (which is beyond the scope of this article), antitrust agencies are ready to anticipate future trends, even at the early stages of a market’s development, and take preventative action.

Merger control

To date, there does not appear to have been merger control reviews of deals involving crypto exchanges. There are, though, at least three reasons why such scrutiny cannot long be avoided.

M&A involving crypto exchanges appears likely to increase. As noted above, size – number of users and volume of transactions – is an important advantage in exchanges achieving greater liquidity and enhancing their reputation and awareness among users. Organic growth is one way to expand. The acquisition is another. And of the two, acquisition may well become more common for the following reasons.

Crypto exchanges have lost substantial value over the past 18 months, creating opportunities for acquirers to purchase targets at a discount. As analysts have noted, crypto companies are cheaper now than they were in 2021, and – on one view – the expectation is that “the most acquisitive companies will likely be the exchanges [themselves]”, as opposed to traditional financial institutions or other non-crypto native acquirers. From the perspective of targets, being acquired may prove more viable than seeking to raise additional investment which – given current macroeconomic circumstances and the sector’s uncertain prospects – may prove difficult.

Acquirers, targets, and deal values may soon reach a size that triggers jurisdictional thresholds and attracts antitrust agencies’ attention. Merger control regimes typically set jurisdictional thresholds based on the parties’ revenues, assets, and/or market shares. Even advanced antitrust regimes have, in some cases, developed low (and flexible) thresholds that render comparatively small deals notifiable. For example:

- In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority has jurisdiction to review deals where (i) the target has UK turnover of >£70 million, or (ii) the transaction results in – or increases – a combined share of 25%+ in the sale or purchase of goods or services of a particular description.

- In Germany and Austria, alternative jurisdictional thresholds based on deal value enable transactions to be reviewed even when the target is relatively small in terms of local or worldwide turnover.

- While jurisdictional thresholds under EU merger control are substantially higher, Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation empowers national agencies – under the Commission’s revised policy – to request a referral of deals to the Commission for review, even when the deal does not meet national (or EU) jurisdictional thresholds.

- Finally, the Court of Justice of the European Union has recently confirmed that deals which close without having to go through ex-ante merger control review may nonetheless be challenged under Article 102 TFEU rules as a possible abuse of dominance.

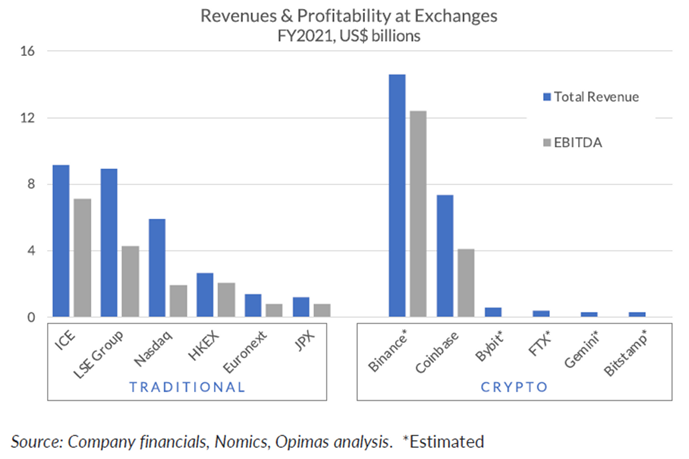

By any measure – user base, transaction volume/value, revenues – crypto exchanges have grown exceptionally large. In 2021, crypto exchanges reportedly achieved trading revenues of $24.3 billion, exceeding equivalent revenue generated by traditional financial exchanges such as the London Stock Exchange (see Figure 7): “Revenue at crypto exchanges increased seven times from the $3.4 billion in sales recorded in 2020 and was 60% higher than the roughly $15.2 billion brought in by traditional securities exchanges”.

Figure 7: Revenues and profitability at exchanges

Coinbase – one of the best-known centralized exchanges – provides a striking example of how highly valued crypto exchanges have become. In its April 2021 IPO, Coinbase achieved a market capitalization of c. $86 billion, although it had fallen to c. $35 billion by April 2022, in line with declines in the value of Bitcoin and Ethereum. Nonetheless, that valuation still put Coinbase alongside companies such as Bank of New York Mellon, Electronic Arts, Twitter, and Motorola. And even today, Coinbase has a market capitalization of more than double Euronext. Recent acquisitions illustrate the potentially high deal values for M&A in the sector, even during the depths of the current ‘winter’. Coinbase, for example, reports total consideration for its 2022 acquisitions of Unbound and FairXchange as reaching c.$260 million and c.$275 million, respectively.

Antitrust agencies have closely scrutinized, imposed conditions on, and even blocked deals involving traditional financial exchanges. Accordingly, antitrust officials may come to crypto deals with a similar mindset – that mergers among crypto exchanges warrant a similar degree of scepticism. They may consider that the economic characteristics of crypto exchanges are similar to those characterizing traditional financial exchanges. Users of both types of exchanges place a premium on liquidity, the security of transactions is paramount, and potential network effects are intrinsic to understanding how competition might play out. Mergers among traditional exchanges have – on several occasions – led to prohibitions or remedies, as shown in Figure 8. It seems likely, therefore, that mergers among crypto exchanges will be subject to similarly intensive scrutiny.

Figure 8: Intervention in mergers of traditional exchanges

| Case | Alleged Competition Concerns | Outcome |

| Merger between Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext (2012) | The merger would create a player with c.90% share of European financial derivatives traded globally on exchanges. | Merger blocked by European Commission |

| Proposed merger between Deutsche Börse and London Stock Exchange (2017) | The merger would have:

(i) created a de facto monopoly in clearing fixed-income instruments (bonds and repurchase agreements); (ii) removed competition for the trading and clearing of single stock equity derivatives (based on stocks of Belgian, Dutch and French companies); and (iii) led the merged entity to divert transaction feeds from its monopoly clearing service towards its settlement division (Clearstream) and away from competing settlement services. |

Merger blocked by European Commission |

| Acquisition by InterContinental Exchange of Trayport (2017) | The merger would have led to ICE restricting the use of Trayport’s software for brokers, exchanges and clearinghouses that compete with ICE in the trading and clearing of European utilities. | ICE ordered to sell Trayport by the UK Competition and Markets Authority |

| Acquisition of Refinitiv by London Stock Exchange Group (2021) | The merger would have:

(i) created or strengthened a dominant position in the market for European government bond electronic trading; (ii) foreclosed trading venues competing with Refinitiv’s Tradeweb in over-the-counter interest rate derivatives, by LSEG no longer clearing their trades; (iii) foreclosed rivals of Refinitiv’s data feed/desktop services by withholding LSEG’s trading data; and (iv) foreclosed rivals in index licensing by denying them access to Refinitiv data. |

Merger cleared by European Commission, subject to commitments to:

(i) divest LSEG’s stake in Borsa Italiana, thereby removing the overlap in European Government Bond electronic trading; (ii) continue providing LSEG’s clearing service for over-the-counter interest rate derivatives on an open basis; (iii) continue providing LSEG and Refinitiv data to downstream rivals |

There are plausible theories of harm, which appear as relevant to M&A among crypto exchanges as any other sector. Any antitrust review of mergers in the crypto sector would have to be based on the evidence, with theories of harm being tested against the facts and circumstances of the deal at hand. Nonetheless, in a merger between, say, two of the largest crypto exchanges, it would not be unreasonable for competition authorities to assess whether the deal might lead to unilateral effects – manifesting through (for example) higher prices for using the exchange post-merger. Similar theories have been applied with respect to traditional securities exchanges, as shown above. Complainants may also raise less conventional concerns. For example:

- Binance’s acquisition of CoinMarketCap (‘CMC’) – a platform that ranks crypto exchanges – attracted criticism (fairly or unfairly) that Binance might use its control of CMC to elevate its position in CMC’s rankings. This may be considered a form of conglomerate effects theory of harm.

- Consistent with recent emphasis on ‘killer acquisitions’ and protecting competition to innovate, agencies may scrutinise acquisitions of crypto exchanges by traditional financial institutions. In particular, agencies might consider whether those transactions have genuine pro-competitive rationales, or aim to dampen dynamic competitive constraints that crypto exchanges represent.

Conduct challenges

Mergers are routinely reviewed by agencies, even if they are non-problematic. The Mergers Intelligence Committee of the UK Competition and Markets Authority reviews around 600-700 mergers each year, whittled down to just approx. 50-60 Phase I investigations, and approx. 10-15 Phase II cases. The European Commission was notified of 405 mergers in 2021, of which 309 were cleared at Phase I under the simplified review regime, and just 7 were referred to Phase II.

In contrast, agencies do not systematically monitor firms’ conduct in the same way as they monitor mergers. Companies do not formally notify conduct agencies for prior approvals, although they may seek comfort prior to implementing contentious practices. Cases are, in large part, driven by complaints that agencies receive, and filtered according to their likelihood of raising genuine competition concerns (among other considerations). To date, it is not apparent that crypto exchanges have engaged in practices likely to raise serious competition concerns or draw properly substantiated complaints. As far as the author is aware, there are no ongoing behavioural investigations into crypto exchanges by antitrust agencies in Europe. While the European Commission reportedly opened an investigation into antitrust aspects of Meta’s Libra project, the project collapsed without a Statement of Objections having been filed.

Private antitrust litigation has occurred, but its record is not strong. In the US, an attempt to sue Bitcoin Cash stakeholders (including the Kraken exchange) over the split between BCH and BSV failed at the first hurdle, since the complainant could not (i) identify a relevant product and geographic market, (ii) adduce sufficient evidence of a conspiracy, (iii) demonstrate a violation under either a per se or rule of reason standard or (iv) establish an antitrust injury. In March 2021, the Court granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss the complaint with prejudice. Further litigation commenced in the UK in July 2022, with a proposed class representative seeking to bring a collective action against four crypto exchanges, alleging an anti-competitive agreement to de-list the BSV coin from their exchanges. As the present author has argued elsewhere, this claim too has fundamental weaknesses, including (i) little or no evidence of an agreement, (ii) no plausible anti-competitive effects on competition, and (iii) no readily apparent loss to BSV investors.

Nonetheless, analogies to the traditional finance sector allows some scope for crystal ball-gazing. For example:

- Most recently, the FCA has announced a market study of the prices and conditions that trading venues impose on users in return for supplying trading data. It has concerns that trading venues are misusing their market power to charge excessively high prices for data feeds, and to discriminate between data customers. In theory, similar issues could arise if a particular crypto exchange became dominant and began charging excessive prices or engaging in discriminatory practices contrary to the rules on abuse of dominance.

- In a consultation on promoting ‘safe innovation’ in crypto markets, the Financial Stability Board discusses the issue of crypto exchanges acting as ‘conglomerates’: “The combination of multiple functions may also give rise to conflicts of interest. For example, a crypto-asset trading platform might conduct market-making on its own platform and impede the fair access of competing market makers. Such conduct may give rise to investor protection, market integrity and conflict of interest issues”. Issues of players with market power both ‘setting the rules of the game’ and offering their own downstream services – in competition with rivals – is not new in competition law. And, without drawing a direct connection to antitrust, the Board refers to competition policy as one of the “specific risk categories related to crypto-asset activities”.

Another example of a proposal raising potential competition issues was the suggestion – made in the wake of FTX’s collapse – that other crypto exchanges could form “an industry recovery fund, to help projects who are otherwise strong, but in a liquidity crisis”. This is an area where a cautious analysis that takes account of industry dynamics is critical. On one (blunt) view, arrangements to prevent rivals from exiting the market could be said to soften competition akin to so-called ‘crisis cartels’, which have traditionally been found to violate competition law. And there could be concerns if requests under the contemplated system led to commercially sensitive information (eg confidential forecasts of future trading volumes and fees) being exchanged. On the other hand, this type of arrangement might – with appropriate safeguards – be implemented in a way that still allows companies to fail through the normal competitive process, but avoids ‘runs on the bank’ (or, rather, runs on the exchange) that weaken confidence and participation in the sector as a whole.

However, these theoretical issues may only arise (or may never arise) until the conduct they entail and actual or potential harms crystallise. In other words, at this stage, it is too speculative to suggest that these practices will feature in public antitrust enforcement in the years to come.

Crypto exchanges and agencies should engage to develop antitrust policies that support the sector

At their best, antitrust agencies can be a powerful ally for innovative and fast-moving industries. Antitrust is premised on the existence of free markets in which companies can thrive or fail based on their own merits. Antitrust is supportive of Schumpeter’s creative destruction. Unlike other areas of regulation, antitrust officials are not interested in establishing detailed rules that specify every aspect of how companies should operate (indeed, many antitrust officials would be appalled at being labelled ‘regulators’). In trying to keep free markets competitive, antitrust should be viewed as capitalism’s critical friend.

But antitrust policy is not uniform. It can be interventionist or permissive, nuanced or blunt, with substantial variation across jurisdictions, sectors, and periods in time. Enforcement is necessarily shaped by different philosophies of antitrust practice, public policy priorities, and agencies’ views on how well particular industries are working for consumers. It is axiomatic that agencies’ decisions are closely grounded in the market dynamics, economic context, and the facts of the cases before them. But competition enforcement is not a purely technocratic exercise either. As one commentator has put it, antitrust is a ‘sponge’ that soaks up external goals, beliefs, and priorities.

Having had little or no interaction with the cryptocurrency sector to date, the shape of antitrust policy in crypto markets is not yet formed. There is a window of opportunity for agencies and crypto exchanges to engage and develop policy that supports, rather than hinders, the sector’s development. And there are (at least) three practical steps that crypto exchanges and agencies ought to take.

First, the pro-competitive benefits of crypto need to be understood, including its role in providing an alternative – or complement – to the traditional financial system. As described above, crypto aims to offer lower-cost transactions that offer greater levels of privacy, security, and a safeguard against inflation. These benefits need to be fully explored to inform the appropriate treatment of deals and practices in the sector. Both crypto exchanges and agencies have roles to play.

- Crypto exchanges should invest in explaining to agencies the positive impact of the industry on competition, rather than waiting for antitrust investigations to make their case. Otherwise, those with an interest in crypto’s failure will be left to create a policy and enforcement environment that is hostile to crypto, rather than aiming to see it flourish. This effort could also explain the legitimate reasons for crypto exchanges to adopt practices that might be the subject of future complaints (g., de-listing particular coins).

- Likewise, agencies can use information-gathering tools to better understand the sector – for example, through market studies, sector inquiries, calls for information, and less formal sourcing of market intelligence, as has been used to review other cutting-edge technologies. While this will require some resources to be set aside, having a clear understanding of how the crypto sector works could ultimately save time and resources when the first notifiable mergers or conduct complaints arrive.

- There are already signs of agencies taking a closer interest in the world of Web3. The UK’s Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum, which includes the Competition and Markets Authority and other concurrent competition enforcers, issued an ‘Insight Paper on Web3’ in January 2023. The paper comments on the perceived benefits and risks associated with blockchain technology and working to “encourage responsible innovation”.

Second, and relatedly, antitrust agencies should use their advocacy function to inform other areas of policymaking. This can be a powerful tool and one that the UK Competition and Markets Authority has used to great effect – for example, in respect of regulations for ride-sharing apps. Other jurisdictions have seen pleas by politicians not to impose regulations that will restrict consumers’ choice of crypto exchanges. Competition agencies could add an authoritative voice in this regard.

Third, agencies should recognize that a wide range of players may have an interest in crypto’s failure, and review complaints accordingly:

- On the one hand, agencies ought to assess each complaint on its merits, while applying an appropriate degree of scepticism, avoiding the temptation to use mergers or behavioural probes to learn about a sector they have not previously reviewed. As discussed above, there are alternative, better-suited tools to learn about the sector.

- On the other hand, crypto exchanges should reflect sincerely on whether particular complaints have a legitimate claim and make proactive changes. Doing so could avoid investigations that harm the sector’s reputation, save the resources expended during investigations, and preserve their credibility with respect to meritless complaints that they decide to contest.

- There may also be instances when crypto firms need to avail themselves of antitrust laws in response to other parties’ conduct that impedes crypto’s development. This is a speculative claim, although there are indications of apparent antitrust harms being considered by players in the crypto space.

There may be other opportunities to shape a well-informed, pro-industry antitrust policy in the crypto sector. What these three examples show is that enlightened self-interest should lead to antitrust agencies and crypto exchanges working together, rather than waiting for the first cases to land.

Conclusion

Lawyers, public affairs personnel, and regulatory specialists in the crypto sector are understandably focused on financial regulation, with new regimes emerging across the US, Europe, and Asia. But financial rulemaking is not their only regulatory challenge. Sooner or later, antitrust cases will come – as they do for all sectors that reach a certain size and prominence.

Crypto is no longer the hobbyist industry that it once was, where thousands of bitcoins are exchanged for a pizza. Crypto exchanges have achieved enormous success. But with success (and scale) comes antitrust scrutiny, particularly in a sector where the economic fundamentals, and emerging market data, suggest that it may be trending towards concentration. It is the wild west no longer; crypto is all grown up.

How should crypto exchanges – as the most visible players in the ecosystem – react? One option would be to take a defensive stance: avoid engagement, fight every claim, and treat antitrust agencies as an obstructive force to be resisted or ignored. That would be a mistake. It would hand the initiative to crypto’s many and varied detractors, who might co-opt antitrust policy as a tool to impede the sector’s advance. The better approach is more nuanced. By helping antitrust agencies understand the sector – its mechanics, its benefits, and its opponents – crypto exchanges can better ensure an antitrust policy that helps the sector thrive.